The relationship between italian culture and the mental health of nurses in the time of a pandemic

Alexandra Antony

The impact that the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) left in its infancy was undoubtedly tragic all over the world.

The initial lack of knowledge present about the transmission, mortality rate, and overall effects on the body left the world in a panic for what to further expect - especially for healthcare workers. Nurses, doctors, and other staff on the frontlines stepped into the worst of the virus each day, having to practice utmost caution in order to prevent spreading the virus to loved ones at home, let alone contract the virus themselves.

Italy was one of the first countries to have a concentrated outbreak of cases as well as deaths. The uncertainty and dangers that healthcare workers first experienced undoubtedly was expected to take a toll on the state of their mental health. Despite the recency of the virus, a few studies were conducted on the mental health of nurses in Italy during the initial months of COVID’s appearance. Although nurses all over the world were fighting this virus, the question arises: How has culture affected the mental health of Italian nurses during COVID-19 so far?

Italy’s culture is known to be one of expression, touch, and physical proximity (Evason, 2017) - which was essentially banned as a result of this virus. An indefinite time period of social-distancing is not exactly ideal for individuals of a low-context culture, and this placed a barrier in the maintenance of many Italian values. Because of this, it is important to look at how Italian culture initially affected the mental health outcomes of nurses during the first few months of COVID-19’s appearance. By looking into this question, a lot can be uncovered about the power of a culture’s effect on a circumstance even as severe as a pandemic.

Figure 2. Annalisa Silvestri, a doctor in Pesaro, Italy (Source: Giuliani, 2020).

Figure 2. Annalisa Silvestri, a doctor in Pesaro, Italy (Source: Giuliani, 2020).

My personal goal after graduating from Binghamton University is to attend nursing school to obtain a bachelor’s degree in nursing as well, therefore, I thought this was a great opportunity to look further into the impact the virus had on nurses during these extraordinary times. I also wanted to combine my current studies in Psychology with what I would like to pursue in the future and specifically look at the mental health of nurses in response to the virus. Each health care worker has been a vital part of saving lives throughout the duration of COVID-19, and directly had to witness many traumatizing instances. It is important to look at culture when also looking at mental health in order to be able to provide as many resources as possible that are suitable to cultural values.

The Initial Impact of COVID-19 in Italy

In the beginning of January, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Chinese CDC) released information about a novel Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) that was initially identified in China, although the exact origins of the virus are still not entirely known (Indolfi & Spaccarotella, 2020).The first case of COVID-19 in Italy was marked on February 21st in the Lombardy region of Italy (Indolfi & Spaccarotella, 2020). This case was only the beginning of a large string of infections, and unfortunately thousands of deaths.

Cases began to rise by 10s into the 100s, and by the beginning of March cases began to soar especially in the northern region of Italy. The rapid incline in cases as well as deaths were suspected to be a direct result from the demographics of Italy, as well as sociocultural values. Specifically, the population consists of 22.8% individuals that are 65 or older (PRB, 2020), and a household in Italy is more likely to consist of three generations (Luciano et al., 2012).

Italy reached its peak of deaths within a day on March 27 at 969 (NYT, 2020). Photographs of healthcare workers spread across social media to portray the lifelessness on each face covered in bruises from the masks worn all day. Workers on the frontlines have continued to experience the ongoing trauma of witnessing the last moments of so many patients without loved ones at their side. In the beginning, shifts would run far over their usual length as more nurses and doctors would contract the virus which only added to the mental drainage (Ser, 2020).

Not only did the patients suffer from not being able to be surrounded by family, but many working on the front lines could not return to their own homes to avoid the risk of infecting family members. As a result, their mental health was further affected due to having to self-quarantine and not have a way to cleanse their thoughts. Frontline workers have also been measured to be of mostly younger age and single (Di Tella et al., 2020), making it more likely that they still live with parents and other family members. Not knowing when they would next see a family member in person, on top of encountering many patient deaths each day further influenced the mental health of frontline workers.

![[object Object]](./assets/5fivmkRrEW/mw-id502_italia_20200401090155_zg-1320x742.jpeg)

Figure 3. Nurses prepare for their shift by putting on PPE in Verduno, Italy (Source: Santaguida, 2020).

Figure 3. Nurses prepare for their shift by putting on PPE in Verduno, Italy (Source: Santaguida, 2020).

![[object Object]](./assets/l8kSwujVsK/screen-shot-2020-11-18-at-10-43-09-am-728x582.png)

Figure 4. New Reported Deaths by Day in Italy between January-July (Source: New York Times, 2020).

Figure 4. New Reported Deaths by Day in Italy between January-July (Source: New York Times, 2020).

Italian Culture and COVID-19

The importance of family and tradition has been a significant factor in Italian culture for many generations, partly because of the belief in the importance of marriage through the Catholic Church - evident by the lower divorce rate in Italy compared to other European countries (Luciano et al., 2012). Despite it occurring less often than it did in the past, it continues to be common for Italians to live with their parents until marriage as Italians tend to hold traditional family patterns (Bimbi, 2009). Younger adults maintain the belief that supporting your parents is a primary duty (Bimbi, 2009), and intergenerational support often exists within Italian households as well from grandparents and other relatives (Luciano et al., 2012).

Consequently, a family in Italy is naturally the backbone of one’s life. Family plays a crucial role as a support system whether it be socially, emotionally, or financially, at least (Bimi, 2009). The emergence of COVID-19 involuntarily took away this support system, resulting in a lack of emotional and social support from a significant source at a time where it has been needed the most. Accordingly, Fiorilli et al. (2018) collected survey data from 363 teachers from various regions in Italy and found that family was the most important source of support when facing burnout. To put into perspective, the other variables that were observed were friends, peers, colleagues, close colleagues, and supervisors. Being a teacher requires an emotional element as does being a nurse, thus a greater chance of experiencing burnout faster (Jeung et al., 2018). This study further supports the argument that the Italian culture being family-focused likely affected Italian nurses that could not receive solace from their loved ones. Family was shown to diminish the burnout that was experienced by Italian teachers the most (Fiorilli et al, 2018), and the pandemic has made it difficult for healthcare workers to merely see them in person.

The feeling of personal connection with other individuals in general has faded as well, especially with frontline workers having to wear layers of personal protective equipment at all times. Italian culture is labeled as a ‘contact culture’ where individuals commonly use nonverbal forms of communication like hand gestures, forward-facing body orientation, and close distance (Evason, 2017). Specifically, Italians are known to stand more directly when speaking to one another, and it has even been found that they stand in closer proximity when conversing than Germans or Americans do (Shuter, 2009), suggesting a greater interpersonal connection during conversation. Italy being a contact culture suggests that Italian healthcare workers have faced a hard hit to their sense of community as well as cultural identity, as their usual rules of conversation have become a threat to their health.

Media Artifact Analysis

Figure 6. Video (Source: Youtube, 2020)

This video from April 22 shows 25 nurses that were housed in a guesthouse next to the Cisanello Hospital in Pisa, Italy to avoid spreading infection to loved ones at home. The housing resembles a motel from the outside, and a small home from the inside. One set of doors into the hospital have a sign posted on them with warning symbols and a message for visitors to ring the bell or call a number before entering. Some of the nurses describe the living situation as strange, and in one interview, a nurse mentions his daily video calls with his family that he looks forward to (La Reppublica, 2020).

Despite the unusual circumstances and separation between the nurses and their families, the video still emanates a sense of community among the residents. One of the shots in the video shows a living room with a comfortable amount of space, and about five nurses can be seen lounging together; a few are sitting on the couch, one woman is on her phone, and another nurse is sitting at a computer. Even without a conversation going, the nurses remain in close physical proximity to each other, with their masks on, clearly representing a companionship among all of them. Other than the individual interviews, residents are constantly shown spending time around one another whether sitting in a room together, or taking time outside the guest house.

A segment of this video that stood out to me the most was when a small group of the nurses were captured standing outside together and talking, where you can hear laughs as well. One of the women is seen smoking too as she joins in on the conversation. This scene symbolizes the nurses as being a large family, despite not even being related at all. Their formation of a small community is formed likely as a result of their shared experiences, though distressful, where they created a sort of emotionally supportive environment between them. In one of the interviews, a man explains that they all continuously care for and uplift one another in respect to the situation which includes playing games together. Even with the involuntary conditions, their value for the familial aspect of their culture clearly breaks through the barrier of not being able to see their own families as can be seen with the closeness between the group.

One of the women says that she cooks every day in order to maintain a feeling of continuity and purpose in her life. This spark of motivation could also be a result of having this support system, and pushes her to keep going. As an integral part of the Italian culture is to care for your family, the nurses are evidently doing exactly this with their temporary family. The use of a guesthouse to shelter nurses possibly exposed to COVID-19 allows them to be able to maintain a social environment, while at the same time not fearing exposing others to the virus. This shows a distinct impact in maintaining the mental health of nurses, even if not to an entirely ideal standard.

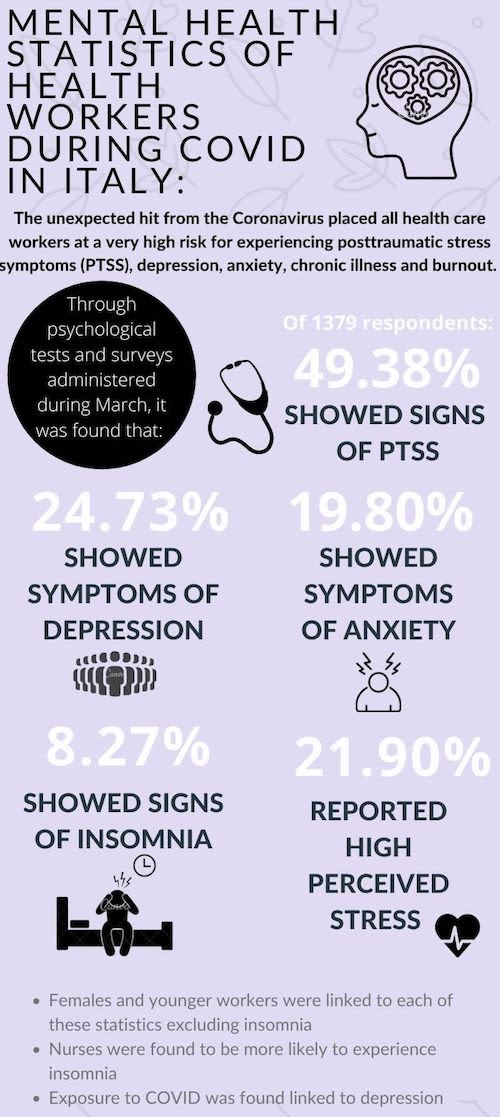

Figure 7. Infographic (Source: Author)

Figure 7. Infographic (Source: Author)

Mental Health Statistics of Health Workers During COVID

The infographic to the left shows the results from data obtained on the mental health of healthcare workers during the end of March throughout Italy. Researchers expected to see a widespread negative impact on the mental health of frontline workers, and their motive was to measure the intensity of this decline. A questionnaire was spread throughout social media to reach as many healthcare workers as possible with a total of 1379 respondents being included in the results (Rossi et al., 2020). Posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, insomnia, anxiety, and perceived stress were measured through the questionnaire. A little over half of the respondents were working on the frontlines at the time (Rossi et al., 2020).

Interestingly, almost half (49.38%) of participants responded with indications of having post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) (Rossi et al., 2020). This condition is an earlier form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that cannot be identified as PTSD yet, but has uniform symptoms to the disorder before a month after the experience including flashbacks, nightmares, and trouble concentrating (Sparks, 2018). Therefore, this shows that in only the first couple of months of the virus’ presence in Italy there was a clear impact on the mental state of many healthcare workers. The condition found to be least experienced by healthcare workers was insomnia at 8.37%, and the data also found that women were less likely to undergo this symptom (Rossi et al., 2020). Participants were also questioned about mental health state when having a coworker in quarantine, hospitalized, or even pass away and it was found that all of these instances were linked to a greater possibility of experiencing stress, depression, PTSS, insomnia, or a combination of all of these (Rossi et al., 2020).

Another study was conducted in Italy concerning the mental health of healthcare workers during the month of March, although it was more focused on sociodemographic data, specifically: age, gender, and relationship status. In this study, 105 out of 145 participants were female. 60.7% of all participants were in a relationship at the time of this survey, and 43.4% worked specifically in COVID-19 units. The average accumulated for life satisfaction was found to be an alarming 2.2 on a scale of 1-10 (Di Tella et al., 2020). As would be expected, nurses and doctors working directly among COVID-19 patients showed greater signs of depression than those that were not, and this trend remained for female participants that were also single (Di Tella et al., 2020). Overall, the healthcare workers assigned to the COVID-19 sections were more likely to be younger and also single (Di Tella et al., 2020).

Looking at the results of both of these studies, it is clear that being directly exposed to the Coronavirus has had massive impacts on the mental health of a majority of health workers at only two months into its appearance. The positive trend of workers not in a relationship and showing signs of depression supports the claim that identifying with Italy’s culture would affect your mental health during the pandemic. Workers have been immersed in the daily horrors of experiencing death of many patients, as well as constantly on their feet without breaks for even using the bathroom. After their shifts would finally come to an end each day, each worker would go home to an empty room to lay down with their day replaying through their head as they would wait until the next day to experience it all over again. The young and single workers likely still live with family as seen in Italian trends, and for this reason they have to avoid all in-person contact with other household members, thus barricading them from an emotional support system or simply even a distraction.

Younger workers were also assigned to COVID-19 units to decrease the exposure of older workers with the virus because of the greater risk, but in doing so they faced the repercussions of having to be separated from their families.

Personal Accounts from Nurses

During the time period when the initial studies about nurse’s mental health were released, personal accounts of nurses spread across the internet on how their personal lives changed due to COVID-19, and especially how it disrupted their culture.

A 26 year old Intensive Care Unit nurse named Nicola from the Lombardy region in Italy described how his everyday habit of having lunch and dinner meals with his whole family had already been halted for weeks by the end of March, and he had not seen his grandparents in fear of infecting them with the virus (Assocare News, 2020). Although he mentioned he would still return to his family home after work, he reported his daily routine to consist of undressing and washing himself in his garage, and then going straight into his bedroom without seeing anyone. Nicola says, “I miss the embraces of my parents and my sister, I miss the smile of my grandmother and the smile of my grandfather,” (Assocare News, 2020).

Another nurse, Laura Lupi, explained an instance she had with a patient who was distressed over a death in the family they could not be present for (UN News, 2020). Her interaction with this patient sounds inhumane from the way she describes it, since she mentions that her face was not even visible due to her being covered by layers of personal protective equipment (PPE). Nurses having to communicate with others while wearing PPE was likely an unusual regulation to get used to at first, especially because of its disruption of personal connection in conversation. This unfamiliar way of communicating plausibly contributed to the increase in depression among healthcare workers during the pandemic.

As reported in May, mental health support provided to nurses in Italy consisted of a resting area in the hospital with healthy snacks along with healthy eating and stress tips (D’Agostino et al., 2020), although success of this implementation has not yet been reported. Although eating healthy is a significant way to keep one’s mental well-being, the implementation of more widespread housing for nurses could be used as shown in the previous video in order to provide greater social support.

Figure 8. A nurse working in Italy with a bruised face from their PPE. (Source: Miranda, 2020).

Figure 8. A nurse working in Italy with a bruised face from their PPE. (Source: Miranda, 2020).

Figure 9. Laura Lupi shares a selfie of herself after removing all of her personal protective equipment (Source: UN News, 2020).

Figure 9. Laura Lupi shares a selfie of herself after removing all of her personal protective equipment (Source: UN News, 2020).

Figure 10. Sign on a balcony in Barcelona, Spain. (Source: Ramos, 2020).

Figure 10. Sign on a balcony in Barcelona, Spain. (Source: Ramos, 2020).

Figure 11. Social distance sign on London Bridge (Source: Melville, 2020).

Figure 11. Social distance sign on London Bridge (Source: Melville, 2020).

Difficulties in Other Countries

In order to effectively claim that Italy’s culture played a role in the severity of mental health among Italian nurses during the outbreak of Coronavirus, the mental health of nurses from other similar and dissimilar cultures should be compared. Specifically, I chose to look at Spain as another high contact culture and the UK as a non-contact culture to compare and contrast mental health effects on nurses during the beginning of the pandemic.

Spain’s communication culture is similar to Italy’s in that it is direct and involves expressing a lot of emotion (Evason, 2018). A study on the mental health outcomes of nurses working during the pandemic in Spain comparing both healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers during the end of March to the beginning of April resembled the trends in the Italian study. A significant increase in signs of depression as well as stress were found when looking at healthcare worker scores on a psychological assessment compared to a non-healthcare worker (Garcia-Fernandez, 2020). This similarity in outcomes seems anticipated, but the results are even more noteworthy when comparing both of these countries to a non-contact culture like the United Kingdom.

In conversation, it has been observed that individuals of British culture tend to withhold emotion and avoid excessive eye contact as this is commonly viewed as aggressive (Kowol & Szumiel, n.d.). They also tend to keep their distance and minimize any physical contact while speaking (Kowol & Szumiel, n.d.). Young adults in Great Britain are also more likely to move out of their family home at a generally young age of 23 years (ONS, 2019), while Italians tend to move out at an average of 30 years old (Eurostat, 2018). This creates a greater independence in British adults at a younger age, thus minimizing the years spent with their family as well as familial ties as strong as that of family-focused cultures.

To the best of my knowledge, no studies have been done on the mental health of nurses within the UK during the beginning of the pandemic which may be in connection with the country’s view on mental health. Although, according to a study done by Bhavsar (2019), a 2014 survey administered in England showed that the southern region of England, specifically London, continues to hold a greater negative mental health stigma.

A UK statistic released in 2019 revealed that female suicide rates among nurses were highest at 23%, and a majority of them did not seek out a mental health resource (Hancock, 2020). This drastic increase in suicide most likely leads directly from the mental health stigma present in the UK, but it is questionable whether this stigma stems from the UK being a non-contact culture. Because of this, nurses in the UK may be more likely to hold the mindset that reaching out for help translates as weak or inappropriate. Therefore, it is important to take this into consideration for providing sufficient resources to nurses in the UK especially during the pandemic, where the toll on mental health begins to accelerate - possibly decreasing the likelihood of nurses reaching out for help.

Conclusion

Despite the eruption of COVID-19 forcing nurses to isolate from family, encounter dangerous conditions, and have many questions left unanswered, each worker has put these concerns aside and continued to fight each day to save each life they come across.

Culture encompasses a large portion of an individual’s life, especially perspective, and a change within one’s culture directly changes what one is accustomed to. This was evident with COVID-19 taking away the usual ways of communication between Italians, and how it affected nurses at a time when they were especially mentally vulnerable. Using this information, mental health services can be tailored to different cultures in order to prevent further damage to mental health, and support all of the frontline workers putting their lives at risk each day.

Coronavirus cutting off one of the most integral parts of Italy’s culture has indeed made it more difficult for frontline workers to cope with the emotional tolls, but at the same time it has kept a flame ignited inside of them. Although the emphasis of family within Italian culture makes it harder to be apart, it still undoubtedly creates a placeholder for intrinsic support and a motivation to continue to look forward to being together again.

References

A.G.E. Graphics. (2020) Thank you nurses sign. [Graphic]. https://www.cheapyardsignsage.com/products/thank-you-nurses-doctors-signs-package-of-5-or-10

Assocare News. (2020, March 25). Coronavirus, CGIL, CISL, UIL e Ministero Salute siglano protocollo per sicurezza lavoratori della sanità. Assocare News. https://www.assocarenews.it/infermieri/sindacato-e-politica/coronavirus-cgil-cisl-uil-e-ministero-salute-siglano-protocollo-per-sicurezza-lavoratori-della-sanita

Beaulieu, C. (2006). Intercultural study of personal space: A case study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 34(4), 794-805.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02571.x

Bendandi, P. (2020). Italian Families. [Photograph]. Life in Italy. https://www.lifeinitaly.com/culture/italian-families-then-and-now/

Bhavsar, V., Schofield, P., Munshi, J.D., & Henderson, C. (2019). Regional differences in mental health stigma—Analysis of nationally representative data from the Health Survey for England, 2014. PLoS One. 14(1). https://doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0210834

Bimbi, F. (2009). The Family Paradigm in the Italian Welfare State (1943-1996). South European Society and Politics, 4(2), 72-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608740408539571

Corner, M. (2020). Two people wearing masks in Milan, Italy. [Photograph]. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/11/15/covid-19-may-have-been-in-italy-as-early-as-september-2019/

D’Agostino, A., Demartini, B., Cavallotti, S., & Gambini, O. (2020). Mental health services in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 7(5), 385-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30133-4

Di Tella, M., Romeo, A., Benfante, A., & Castelli, L. (2020). Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID ‐19 pandemic in Italy. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 26(6), 1583-1587. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13444

Eurostat. (2018, May 15). Bye bye parents: When do young Europeans flee the nest? https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20180515-1

Evason, N. (2017). Italian Culture. Cultural Atlas. https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/italian-culture/italian-culture-communication

Evason, N. (2018). Spanish Culture. Cultural Atlas. https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/spanish-culture/spanish-culture-references#spanish-culture-references

García-Fernández, L., Romero-Ferreiro, V., López-Roldán, P. D., Padilla, S., Calero-Sierra, I.,Monzó-García, M., Pérez-Martín, J., & Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. (2020). Mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers. Psychological medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720002019

Giuliani, A. (2020). Annalisa Silvestri. [Photograph]. The Atlantic.https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-italy-photos-doctors-and-nurses/608671/

Hancock, C., & Marsat, N. (2020, August 28). How is COVID-19 impacting the mental health of nurses? Health Europa. https://www.healtheuropa.eu/how-is-covid-19-impacting-the-mental-health-of-nurses/102404/

Indolfi, C., & Spaccarotella, C. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 in Italy: Fighting the pandemic. JACC Journals. 2(9), 1-5. https://www.jacc.org/doi/full/10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.03.012

Jeung, D., Kim, C., & Chang, S. (2018). Emotional labor and burnout: A review of the literature. Yonsei Medical Journal. 59(2), 187-193. https://doi/10.3349/ymj.2018.59.2.187

Kowol, A., & Szumiel, E. (n.d.). United Kingdom: communication, negotiations and cultural background. http://works.adamkowol.info/UK.pdf

La Repubblica. (2020, April 22). Coronavirus, infermieri che a Pisa vivono nella foresteria: "Da un mese non vedo la mia famiglia". [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1vEodHKs3A

Melville, T. (2020). Social distancing sign on London Bridge. [Photograph]. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/861aee73-83ec-4465-9ac0-99bd0a76c8ee

Miranda, P. (2020). [Untitled Photograph of Nurse with Bruised Face]. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52784120

New York Times. (2020, November 14). Italy Coronavirus map and case count. Italian National Institute of Statistics. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/europe/italy-coronavirus-cases.html

New York Times. (2020). Italy Coronavirus map and case count. [Graph]. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/europe/italy-coronavirus-cases.html

Office for National Statistics. (2019, February 18). Milestones: journeying into adulthood. ONS. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/milestonesjourneyingintoadulthood/2019-02-18

Population Reference Bureau (2020, March 23). Countries With the Oldest Populations in the World. PRB. https://www.prb.org/countries-with-the-oldest-populations/

Ramos, D. (2020). People applaud from balcony… Barcelona, Spain. [Photograph]. Bloomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-31/how-to-build-community-while-social-distancing

Rossi, R., Socci, V., Pacitti, F., Lorenzo, G.D., Di Marco, A., Siracusano, A., & Rossi A. (2020). Mental health outcomes among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. 3(5). JAMA Network. https://doi/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185

Santaguida, M.T. (2020). Nurses put on their personal protective equipment before a shift last month in the intensive-care unit in a new COVID-19 hospital in Verduno, Italy. [Photograph]. Market Watch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/this-looks-like-operating-in-a-war-zone-italian-doctor-who-treated-italys-patient-1-battles-to-save-lives-from-coronavirus-2020-04-01

Ser., M. (2020, February 22). Medici e infermieri in trincea: "Turni infiniti, stress e paura". La Stampa.https://www.lastampa.it/cronaca/2020/02/23/news/medici-e-infermieri-in-trincea-turni-infiniti-stress-e-paura-1.38504098

Shuter, R. (2009). A field study of nonverbal communication in Germany, Italy, and the United States. 44(4), 298-305. Communication Monographs. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757709390141

Sparks, S. (2018). Posttraumatic Stress Syndrome: What Is It? J Trauma Nurs. 25(1), 60-65. https://doi/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000343

UN News. (2020, April 07). First Person: 'Fate' of Italian Nurse, and Countless Other Health Workers, Depends on Protective Clothing. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061222

UN News. (2020). Laura Lupi. [Photograph]. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061222