The French Language and Identity in Quebec

By Heera Narang

Introduction:

In the summer of 2023, I studied abroad in Canada. Specifically, my classmates and I spent three weeks in Quebec City, the provincial capital of Quebec. I was almost immediately blown away by how distinct Quebec felt from both my home in the United States and the neighboring province of Ontario. Despite being close enough to share a border, Quebec has an identity all its own - one with the French language as a central tenet. As someone who is majoring in French Linguistics, I was captivated. I decided to dig deeper. This project was the eventual result.

Quebec is the only one of Canada’s thirteen provinces and territories with French as its sole official language. Only one province - New Brunswick - is officially bilingual, while the others have only English (Canadian Heritage, 2019). This distinction showcases the unique role French plays in Quebec’s society. Unlike the United States, where English has dominated since the early days of colonization, the role of French in Quebec has not always been so certain. Language, and the discourse surrounding it, has played an integral part in the development of Quebec into what it is today. In this project, I will be specifically examining language and how it relates to identity in Quebec. Specifically: Why is the French language so crucial to the idea of a québécois identity, and how has that belief been reflected in policy?

Figure 1: A map of modern-day Quebec. (Illustration by WorldAtlas, 2023. https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/canada/quebec.)

Figure 1: A map of modern-day Quebec. (Illustration by WorldAtlas, 2023. https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/canada/quebec.)

Historical Domination

In 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier landed on the Gaspé Peninsula. There, he planted a cross, symbolizing the authority of the French crown and marking the beginning of more than two centuries of French control of the area. (Blood 2020). With the establishment of three cities in the early 1600s - Trois-Rivières, Montréal, et Québec City - settlement commenced. Many facets of Québécois identity began here - the colonists of “Nouvelle France” (New France) brought their language and Catholicism with them across the Atlantic, two things that remain important in the Quebec of today. As the colonies developed, their inhabitants were faced with a new set of challenges, including conflicts with the English and the Iroquois, and long, difficult winters. However, they managed to survive, even prosper, and in the process formed the beginnings of a distinct identity (Blood 2020).

In 1759, a turning point: after a defeat in the Seven Years’ War, France ceded Canada to the British. Suddenly, francophone Canadians were part of an empire that was “hostile to their culture, to their laws, to their language, to their tradition, and especially to their religion” (Blood 2020, 78) (translation mine). As such, the history of French Canadians is one that has been, at different points in time, one of both the colonizers and the colonized. There was a new fear that the French Canadian identity might very well disappear - a fear that has persisted in Quebec until the present.

The policies of Canada’s new leadership did little to dissuade this. Although officially their language and culture were recognized, the government passed a series of repressive policies. For some time, whether on the basis of language or religion, French Canadians were treated as less than their English counterparts. There was, for example, the Test Act, a declaration against certain catholic beliefs (most French Canadians were Catholic, as opposed to the typically-Protestant English) and of loyalty for the British crown. Catholics were also banned from holding public office as long as they continued to practice.

In 1766, the attorney general proposed settling the disputes between francophone and anglophone citizens with the assimilation of francophones. The idea was to administrate the province in a way that would attract more English-speaking immigrants, with the goal of eventually outnumbering the French-speakers.

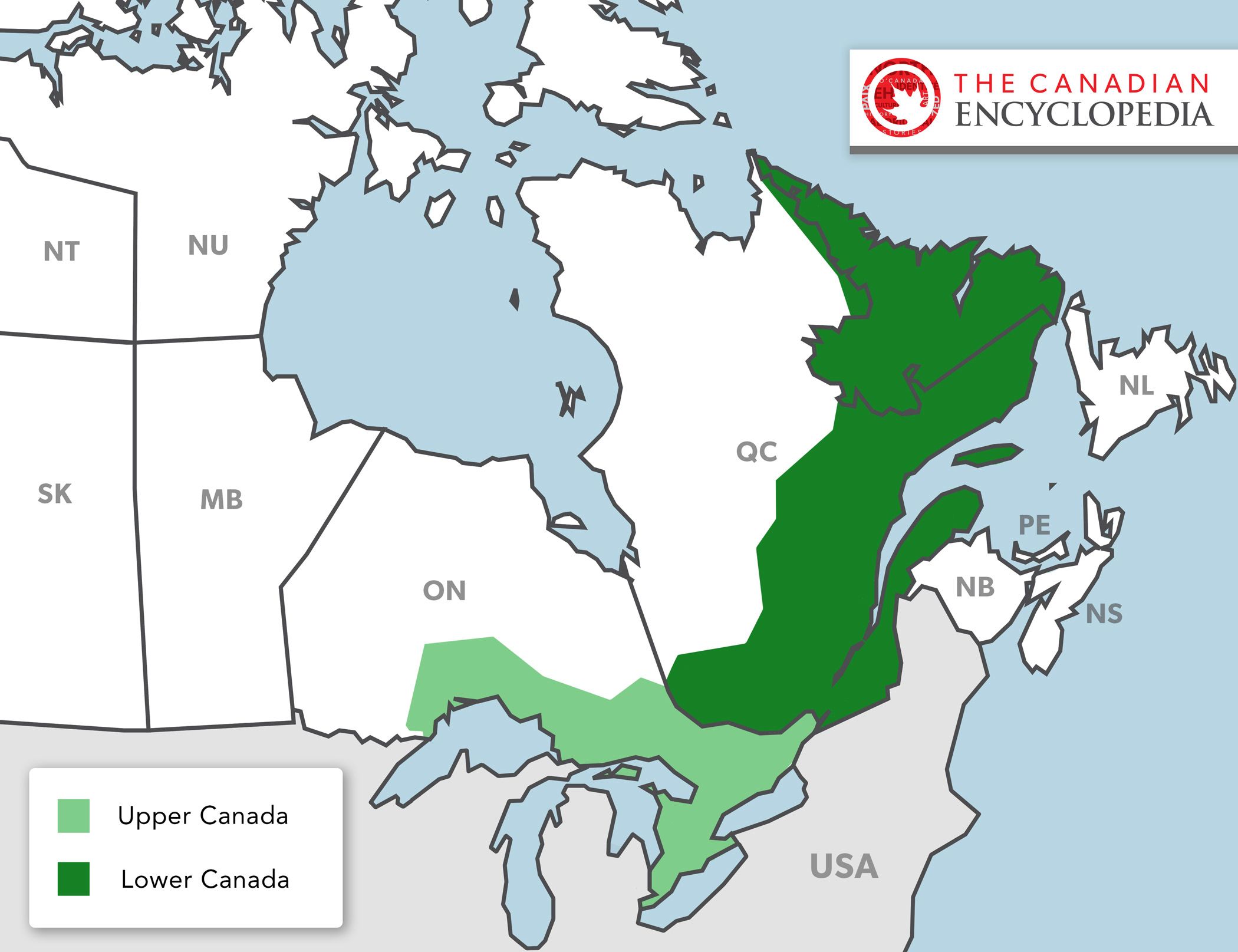

In 1791, in response to widespread migration of loyalists from the American colonies, Canada was divided into two provinces: Upper Canada, primarily anglophone (today Ontario), and Lower Canada, mostly francophone (today Québec). Each province had a Legislative council and an Assembly Chamber. Under this system, the inhabitants of Lower Canada were at a political disadvantage. Every law passed by the elected Assembly had to be approved by the Council, whose members were appointed by the English authorities. After that, it had to be either given royal sanction or rejected by the (also English) governor (Blood 2020).

The rise of nationalism

The beginnings of nationalism tied to the ethnic identity of French Canadians can be said to have begun with the failure of the Patriot Rebellion (1837-1838) (Oakes and Warren 2009, 30), led by the president of Quebec’s legislative assembly, Louis-Joseph Papineau. The Patriots were primarily of French descent, although their ranks included some English and some Irish. In the face of British repression, they hoped to establish a Canadian nation that was “independent, bilingual, and secular,” drawing from the same republican ideas as the French and American Revolutions. However, the revolt was quickly put down by the British Army. 851 Patriots were captured and scattered in various prisons, 60 were sent to the penal colony of Australia, and 12 were publicly hanged in Montréal. Others, including Papineau, fled to the United States to avoid imprisonment or worse (Blood 2020, 81).

To avoid any further insurrections, the governor of British Canada, proposed the unification of Upper and Lower Canada - a plan that would have declared English the sole official language and forbidden the use of French (Blood 2020, 81). Such measures focused on the immediate need to fill Lower Canada with subjects loyal to the British Crown (Oakes and Warren 2009, 31).

Figure 3: A map of Upper and Lower Canada in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. (Illustration, Map of Upper Canada and Lower Canada 1791-1841, n.d., The Canadian Encyclopedia)

Figure 3: A map of Upper and Lower Canada in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. (Illustration, Map of Upper Canada and Lower Canada 1791-1841, n.d., The Canadian Encyclopedia)

By 1867, the time of Canadian confederation (when the various British colonies were formed into a federal union), “Canada was [...] a Dominion of the British Empire and French Canadians the descendants of a conquered nation” (Charbonneau 2017, 495). To survive as a people, French Canadians therefore turned to ethnic nationalism, based on traditional catholic and rural values (Oakes and Warren 2009, 31). “Led by those most sensitive or vulnerable to the changing sociopolitical situation, Quebecois developed nationalist ideologies in order to define their identity and interests in a society suddenly become plural at the center” (Handler et al., 1984, 58).

The divisions between French and English Canadians were no less apparent after Confederation. There was, for example, the 1885 Riel Rebellion, where a group of Metis (Half French and half Indigenous) tried to gain independence for Manitoba in response to increasing anglophone migration. In the end, its leader was hanged and became “a hero for French Canadians and a traitor for English Canadians” (Fenwick 1981, 202).

These conflicts had several different effects. “They point to the willingness of anglophone Canadians to limit or abolish the rights of francophone and Catholic Canadians outside of Quebec, and the struggle of francophone and Catholic Canadians to maintain these rights - to survive as a group” (Fenwick 1981, 203). They also weakened the position of French Canadians outside of Quebec, contributing to increased physical isolation between the linguistic groups.

Urbanization and industrialization reshaped the conflict as Quebec versus the rest of Canada, as people moved to the cities. The formation of a new bureaucratic middle class and an urban working class shifted concerns over minority rights into concerns about economic inequality, which was divided more along linguistic lines than religious ones. “And since access to economic power and equality in the new industrial order came to be determined more along linguistic lines than religious lines, language replaced religion as the primary line of communal cleavage in Canada.” (Fenwick 1981, 204).

Additionally, while French Canadian communities outside Québec had survived by being largely self-sufficient pre-industrialization, afterwards increased ties to the outside economy necessitated many to learn English. In some cases, the next generation were raised as monolingual English speakers, leading to a decline in the French-speaking population in such areas.

While there were some government efforts to combat this - the 1944 foundation of Hydro-Québec (today one of Canada’s biggest power companies) aimed to break up the anglophone monopoly on electricity - the trend persisted until about the 1980s (Bailey 2003).

The end of the 20th century saw the rise to power of René Levesque and the “souverainiste” movement. They advocated for Quebec sovereignty, ideally with some sort of economic agreement with English Canada, as a “fast track to equality with English Canadians” (Charbonneau 2017, 496). They argued that Francophones had been treated as second class citizens since the time of Confederation and government efforts to change that were “purely cosmetic” (Charbonneau 2017, 496). While the idea of separatism was fiercely divisive, the sentiments behind it were far from uncommon - even politicians against sovereignty called for changes to the status quo in favor of French Canadians.

In 1976, Levesque and his “Parti Québécois” gained their first majority government and enacted a series of policies with these goals in mind, including the passage of the Charter of the French Language (but we’ll get to that.)

This movement culminated in two separate referendums on independence - one in 1980, and one in 1995. Although “no” won both times, the race was very close. In the case of the second referendum, only 50.58% voted against sovereignty - a majority, but only barely (Blood 2020, 151).

Even now, people still identify as Québécois first and Canadian second. A 2003 survey by Statistics Canada found that 66.2% of anglophones described the sense of belonging to Canada as “très fort,” [very strong] compared with 29% of francophones (Oakes and Warren 2009, ). Additionally, when a survey conducted by La Presse, a daily French newspaper, asked if anglophones were “less québécois” than others, the general consensus was “yes.” (Oakes and Warren 2009, 199) - signifying, if nothing else, that the definition of "québécois" falls by popular perception along language lines.

Changing demographics

The 21st century saw Quebec taking in an influx of immigrants from around the world. This has brought with it a significant degree of linguistic diversity - according to the 2001 census, 50.5% of the population had neither English nor French as a mother tongue (Oakes and Warren 2009, 209).

Immigration offers a solution to several demographic problems the province faces, including an aging population and the labor shortage. However, it also raised new questions: what would it take for these new arrivals to become part of Quebec’s society? How much societal change was acceptable as a result?

Many new immigrants are “allophones” - speakers of a language other than French, English, or an indigenous language. Learning French is seen as an essential step on the way to assimilation, and integral to the preservation of Quebec’s culture/identity. There is a unique focus on having immigrants learn the language because of the perception that French’s position in North America is relatively precarious.

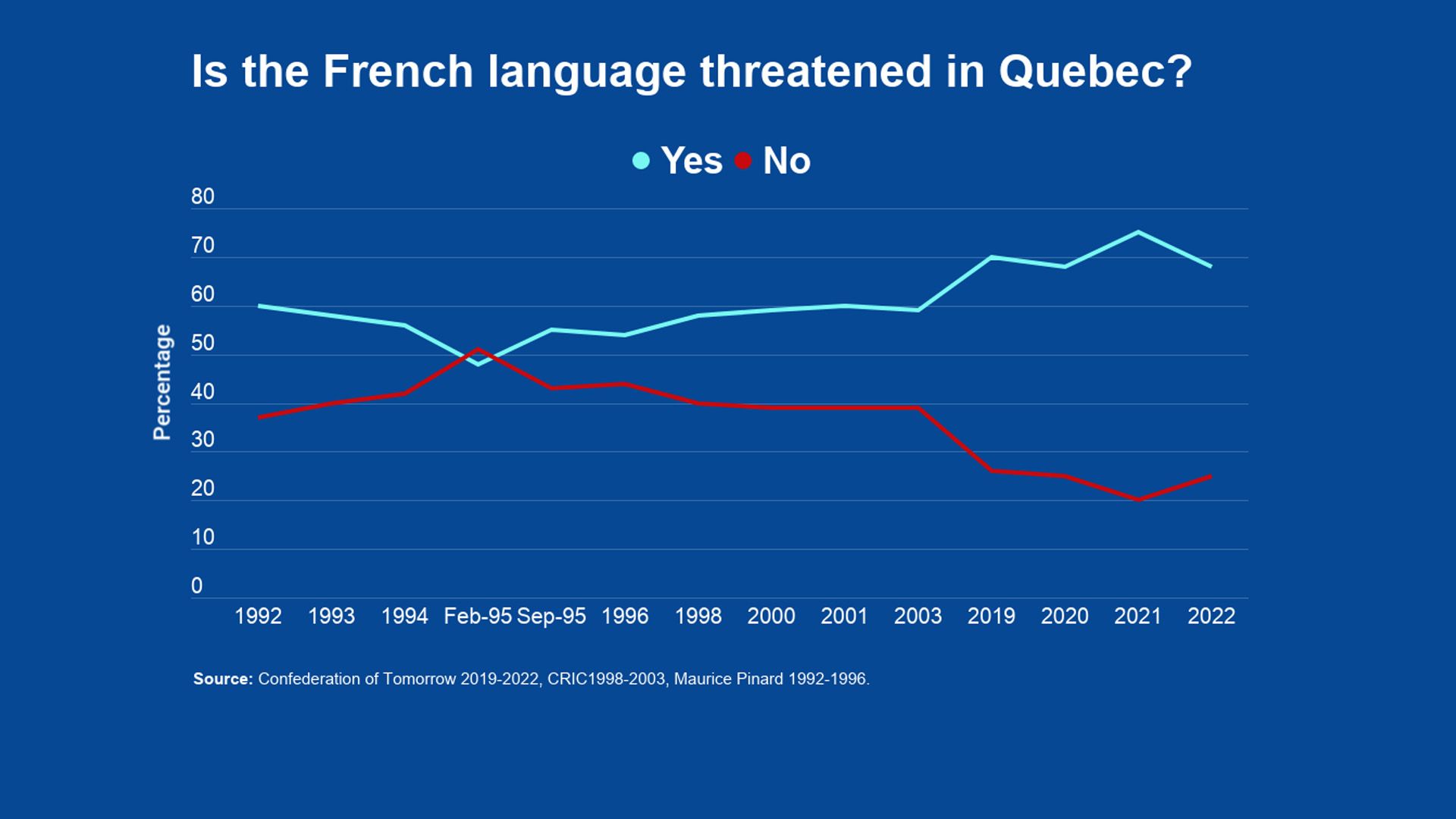

Figure 6: the results of a public opinion survey of French Quebecers. (Graph by Charles Breton et al., 2022. Policy Options. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/june-2022/quebecers-more-pessimistic-than-ever-about-the-future-of-the-french-language/)

Figure 6: the results of a public opinion survey of French Quebecers. (Graph by Charles Breton et al., 2022. Policy Options. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/june-2022/quebecers-more-pessimistic-than-ever-about-the-future-of-the-french-language/)

Photo by Metin Ozer on Unsplash

Photo by Metin Ozer on Unsplash

Data from the Confederation of Tomorrow, which conducts annual studies in partnership with a variety of government agencies, found that roughly two-thirds of Francophone Quebecers agreed that French was threatened in Quebec (Breton et al., 2022). Although this rate has been on the decline since 2021, it is still well above where it was in the 1990s and 2000s.

Beyond a numerical shift, there has also been a demographic one. In 2001, respondents above 55 and those with a university education were overall less pessimistic. By 2022, older generations had become more likely to respond pessimistically, and having university education no longer affected the response (Breton et al., 2022).

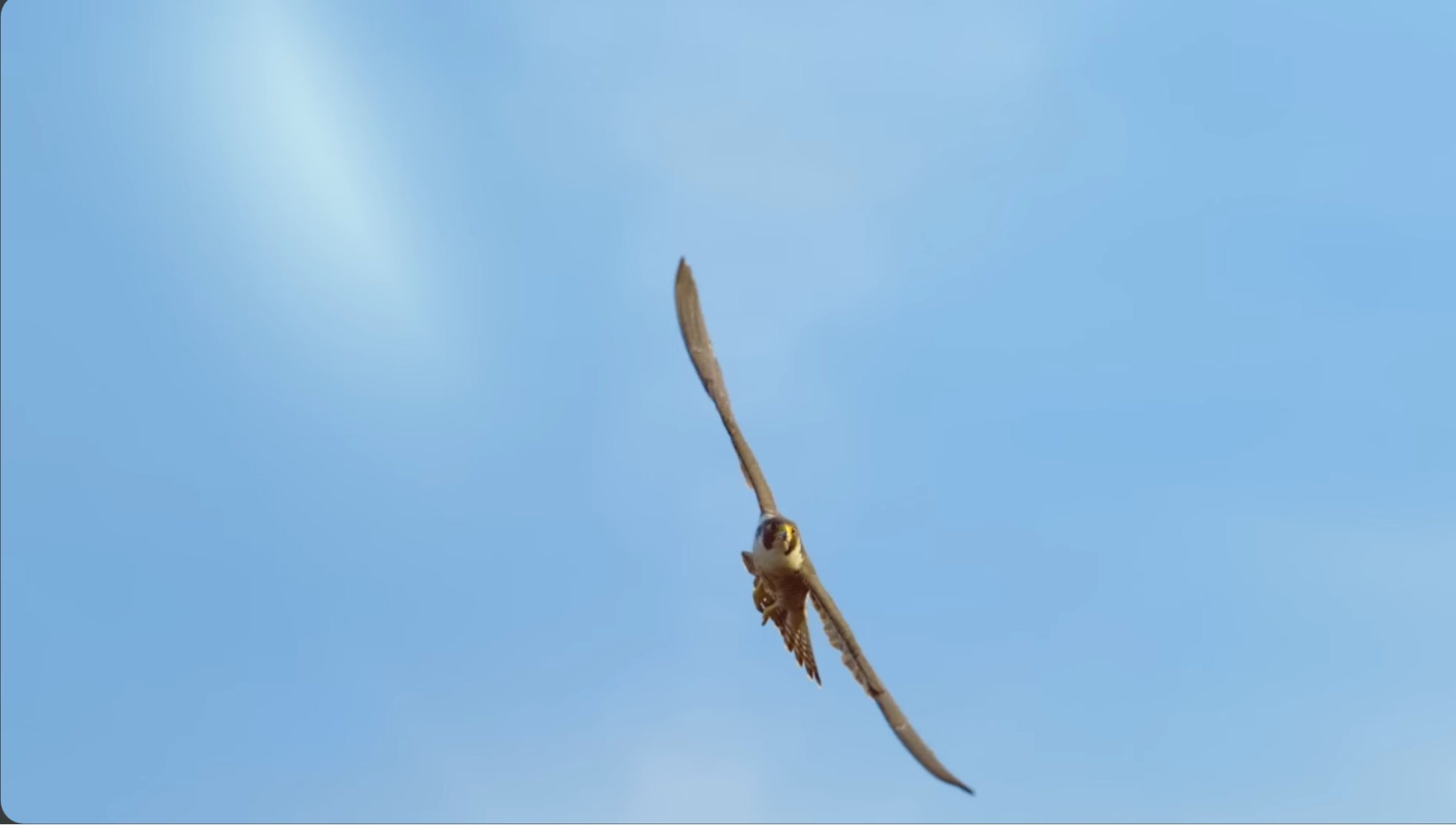

In March of 2023, Quebec's Ministry of the French Language put out a short PSA criticizing the use of "Franglais."

The video styles itself like a nature documentary, featuring clips of a peregrine falcon soaring through the air overlaid with a calm voiceover. However, our narrator is no David Attenborough - though he speaks in French, he tosses in English slang almost every sentence. He calls it a "vraiment sick" bird of prey and says it is known for being "assez chill." Once he's done, the screen fades to black, displaying a brief message: "Au Québec, le français est en déclin. Renversons la tendance." Roughly translated: "French is in decline in Quebec. Reverse the trend."

The PSA in question, published on the Ministry of the French Language's official YouTube Channel.

Figure 7: In Québec, road signage is almost exclusively in French. (Photography by Chris Donovan, Stop Sign in Quebec, 2019. Canadian Geographic Photo Club https://photoclub.canadiangeographic.ca/media/7072385)

Figure 7: In Québec, road signage is almost exclusively in French. (Photography by Chris Donovan, Stop Sign in Quebec, 2019. Canadian Geographic Photo Club https://photoclub.canadiangeographic.ca/media/7072385)

There are several aspects of this video that are worth discussing.

For starters, there's the intended message: that those who use Franglais are somehow bastardizing the French language, and that it is necessary to limit the influence of English on the French language in Quebec. This point is underscored by the visuals - while a falcon soars through the air, majestic and serene, the narrator speaks extremely casually. Calling it a mismatch in tone would be putting it mildly.

A still from the PSA video, showing a peregrine falcon in flight.

A still from the PSA video, showing a peregrine falcon in flight.

However, it is reflective of a fairly common desire to keep Quebec's French "pure." Although French has its fair share of borrowed words - "coton" (cotton) and "orange" both come from Arabic (Spector 2023) - there is a perception of English influence as something to be avoided. This can be seen in some of the vocabulary unique to Quebec. Whereas someone from France might use anglicisms such as "le chewing-gum" and "le pull-over," the Québécois tend to use "le gomme à macher" and "le chandail" instead - alternatives that sound more "French." Quebec, as a francophone community in the midst of a majority-angophone North America, has become especially protective of its language, and this video reflects that.

Also, this PSA compares the French language in Quebec to an endangered species - something to be respected and defended. Beyond his use of Franglais, the narrator makes a point of highlighting the uncertain nature of the falcon's future - it is "sketch," he says. Many who are worried about the status of French in Quebec express similar concerns for the future.

A still from the end of the video, urging action on the part of the viewer.

A still from the end of the video, urging action on the part of the viewer.

Figure 8: Simon Jolin-Barrette, Quebec's Minister of the French Language. (Photograph by Denise Bombardier, 2020. Vigile Québec https://vigile.quebec/articles/simon-jolin-barrette-a-t-il-un-avenir)

Figure 8: Simon Jolin-Barrette, Quebec's Minister of the French Language. (Photograph by Denise Bombardier, 2020. Vigile Québec https://vigile.quebec/articles/simon-jolin-barrette-a-t-il-un-avenir)

The ideologies surrounding language preservation in Quebec are not unique, but the method of carrying them out might be.

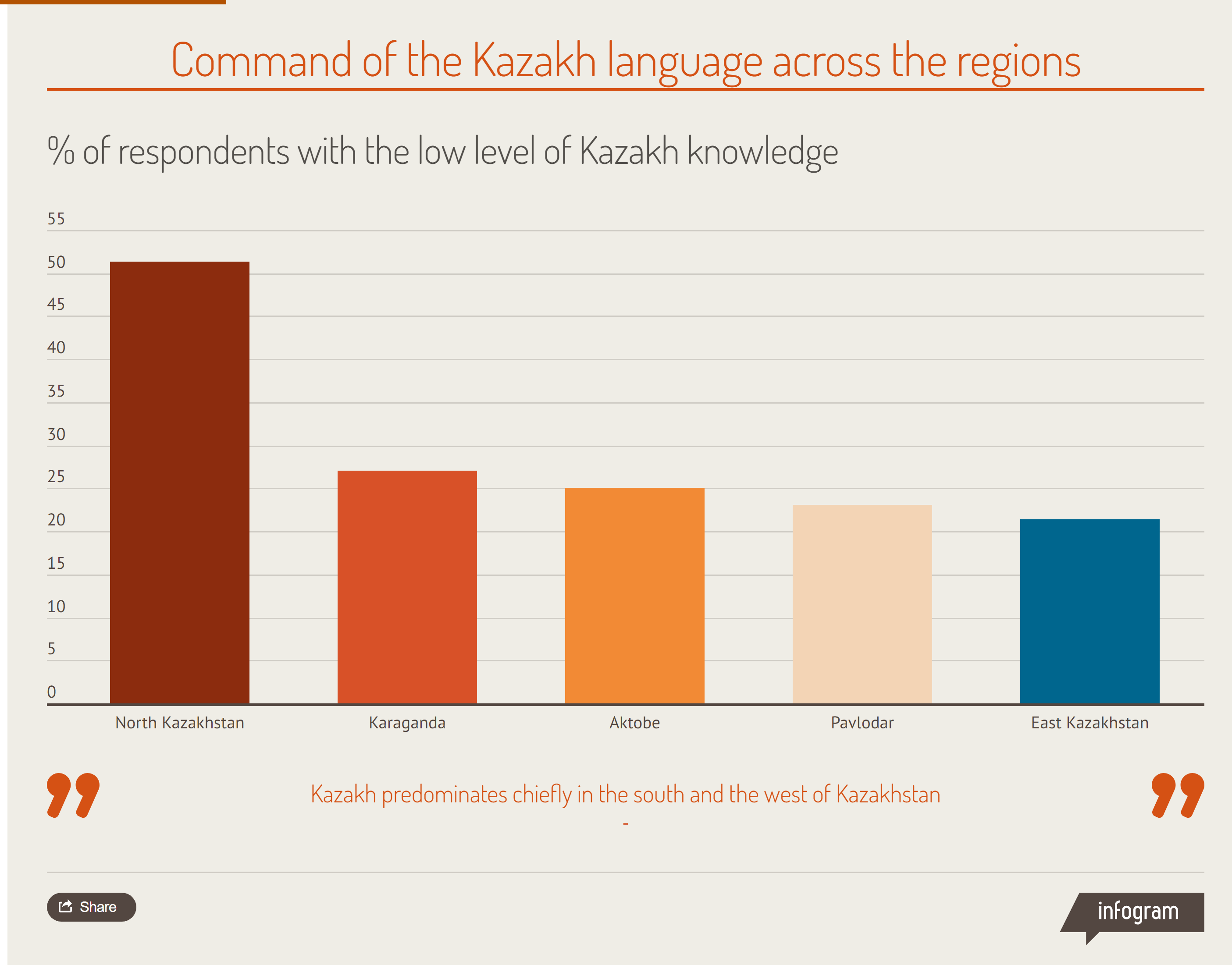

Kazakhstan, although a long way from Quebec, is also in the process of instituting a language policy - in this case, a trilingual one, focusing on teaching Kazakh, Russian, and English. More than 98% of the population lists Kazakh as their native language, although less than three-quarters are fluent, showing again the role of language as a determinant of ethnic identity.

The Soviet Union's policies of "linguistic and cultural Russification" (Moldagazinova 2019) have led to Russian being widely understood, even today. During that time period, like during the British conquest of Quebec, the language of a majority ethnic group (Kazakhs) was more or less displaced by the language of the ruling country (the Soviet Union).

Unlike Quebec, however, Kazakhstan aims to increase proficiency of all three languages, rather than prioritizing one by pushing out the other. Although Kazakh is slowly replacing Russian as the language of the government, Russian remains in use in professional spheres. Now, the government is pushing English in order to help its citizens participate in an increasingly global world order- a logical enough concern, but nonetheless an interesting contrast. As we will see in the following sections, Quebec, rather than shifting the language of its populace to better fit the international sphere, has instituted policies that seek to make international influences within its borders (such as immigrants and businesses) adopt French.

A central part of the PSA's message is the repetition of the claim that French in Quebec is actively in decline. This is a claim that has been somewhat contentious. It has been repeated by several figures in Quebec's government. Simon Jolin-Barrette, the Minister of the French Language, said that “on this continent and in Canada, the survival of the French language is threatened” (Ross 2022) - a claim that he would later use to justify the passage of Bill 96. He cites low rates of linguistic transfer among immigrants - while two-thirds said they spoke French in 2010, less than half say the same today.

However, Jack Jedwab, president of the Association for Canadian Studies, argues that projections that seem to show a decline in the use of French are "ethnically driven" (Fletcher 2021). He argues that they exclude second-generation French speakers, such as Haitian or Arabic people, or others who are "equally French" (Fletcher 2021). Jedwab raises an interesting point: the line between who "counts" as a French speaker and who doesn't is extremely undefined and can even vary from source to source.

Still, in Quebec, that distinction carries some importance. From a 2001 government statement: "in order to feel at home in Québec, [new arrivals] must first feel at home with the French language (Oakes 2009). More than a means of communication, French has become an integral part of the Québécois identity, to the point that learning it is seen as essential step for assimilation and integration. Perceived threats to the language are worrisome because they present a threat to the fabric of Quebec's society. It is in this way that this PSA also evokes nationalist ideals. The incursion of English via "Franglais" is in this view not merely a question of adopting slang, it is an unacceptable compromise on a fundamental part of the Québécois identity.

As Lévesque himself wrote: “Being ourselves is essentially a matter of keeping and developing a personality that has survived for three and a half centuries. At the core of this personality is the fact that we speak French. Everything else depends on this one essential element” (Handler et al., 1984, 60).

Figure 9: A graph showing rates of low Kazakh proficiency across various regions of the country. (Command of the Kazakh language across the regions, 2008. “Alternativa” Center of Current Studies. https://voicesoncentralasia.org/trilingual-education-in-kazakhstan-what-to-expect/)

Figure 9: A graph showing rates of low Kazakh proficiency across various regions of the country. (Command of the Kazakh language across the regions, 2008. “Alternativa” Center of Current Studies. https://voicesoncentralasia.org/trilingual-education-in-kazakhstan-what-to-expect/)

Language Legislation since the 1970s

A series of legislative measures have been passed since the 1970s with the express goal of promoting the use of French in various aspects of society. This is seen as a pathway to protecting the unique Québécois identity so many were trying to preserve.

First, there was Bill 101, also known as the Charter of the French Language, passed in 1976. It pushed a policy of unilingualism, viewing Quebec as “an overwhelmingly Francophone nation-state in embryo” (Coleman 1981, 476).

One of the bill’s most significant impacts was the limiting of access to English schooling to:

“Children whose mother or father had received their primary schooling in Quebec in English.”

“Children whose father or mother lived in Quebec at the time of the promulgation of the law and who had received their primary instruction in English outside Quebec.”

“Children who in the previous school year had received legally instruction in English in the public school system.”

“Younger brothers and sisters of the latter”

(Coleman 1981, 469)

The end goal was to restrict freedom to choose English language education to those anglophones with “historic” roots in Quebec. This affected two main groups: the children of immigrants (who became the so-called “children of Bill 101”) and English Canadians who moved to the province later in life. In its first year of operation, the bill saw a 6.4% rise in the number of allophone children enrolled in French-language schools, and for the first time a majority of allophone parents with newly school-aged children sent them to French-language kindergartens (Coleman 1981, 470-471). At the same time, the English school system saw a 15% drop in enrollment after the first two years (Coleman 1981, 471). Between 1981 and 1971, 12% of native English speakers left the province, likely in response to the passage of the Charter (Oakes and Warren 2009, 195). The lasting effects are striking: from 1976 to 2015, the percentage of students attending French school whose first language wasn't French more than quadrupled, rising from 20 per cent to 90 per cent (Stevenson and Nakonechny 2022)

This is an initiative that has been backed almost continuously by the provincial administration. “Every single Quebec government since 1977 [...] have supported the fundamental elements of Bill 101” (Charbonneau 2017, 501). This includes the idea that because French is a minority language in North America, immigrants should have to send their kids to French schools to keep the province from being overwhelmed by non-French speakers that would “threaten the linguistic equilibrium of the province” (Charbonneau 2017, 501). The rhetoric behind Bill 101 again reinforces fears about “cultural pollution” - that the increased presence of other groups could erase what makes Quebec's national culture distinctive.

Nationalist groups argued the bill wasn’t restrictive enough. Some feared it would allow francophones already enrolled in English schools “to continue living on the margins of the Québécois nation” (Coleman 1981, 469), and called for the return of such children to the French school system. The Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal even suggested limiting English schooling to children with English as a mother tongue and whose parents lived in Québec when the law took effect - a plan that would have led to “the eventual disappearance of English language schools” altogether (Coleman 1981, 470).

More recently, there was the passage of Bill 96, which served as an update to the Charter of the French Language. Like Bill 101, its primary goal was to promote and preserve the use of French across many aspects of Quebec’s society. It is extremely explicit about such foals - it goes so far as to add a sentence to the preamble of the Charter, recognizing Quebec as “ the only French-speaking State in North America,” and goes on to say that that “that confers a special responsibility on Québec, which intends to play a leading role within La Francophonie (Bill 96).”

Bill 96 imposed a cap on English CEGEP (post-secondary) enrollment at 2019 levels and increased French proficiency requirements to graduate, even for anglophone rights holders. It also greatly limited access to English government services to a set of specifically defined groups, including new immigrants. However, after 6 months, these immigrants must communicate with the government in French. In addition to that, it requires businesses with between 5 and 49 people to disclose how many of their employees don’t speak French, and requires those with more than 25 employees to use French as their common language.

Has Quebec Gone Too Far?

Bill 101 was met with criticism from the other side as well. Groups from the employer class argued that freedom to choose the language of schooling should be offered to all children, and that at the very minimum English Canadians from outside Quebec should be able to send their children to English schools. Associations representing new immigrants were unhappy that the bill included no provision for English second-language education.

Also, figuring out who qualified for English education and who didn’t was a messy process. Bill 101 led to the establishment of “écoles passerelles” [bridging schools] - English institutions that students would attend for a few months to a year, which then counted as them having received English schooling in Quebec and allowed them to transfer to an English school (Charbonneau 2017). By 2002, roughly 1000 students per year used this method to acquire access to English-language schools, the vast majority having attended non-subsidized school for less than a year.

The Quebec government passed Bill 104 to close this loophole by ruling that unsubsidized schools were not considered “part of a valid curriculum.” This decision was contested in court by a group of parents. The case eventually reached the supreme court, which ruled that while “it is acceptable for the province to limit access to subsidized English schools” (Charbonneau 2017, 503), the way that they had gone about it was not. Instead of judging a person’s eligibility for minority-language schooling by a set list of criteria, the court said that it should instead be evaluated whether or not the person had shown a “genuine commitment” to become part of the linguistic minority.

Since attendance at a non-subsidized school constituted one of the only ways to show this “commitment,” this meant in effect that “the very wealthy in Canada can now purchase the right to be considered a member of the minority in provinces” (Charbonneau 2017, 504-505).

More recently, there has been widespread indigenous opposition to Bill 96 (Bell and Gunner 2022). Indigenous students already have very low graduation rates, and some worry that increased French proficiency requirements could impose an additional burden on them. Many indigenous communities are trying to preserve their native languages, and so teaching those to the next generation is a higher priority. For children from such communities, French is often their third language. Daisy House, the Chief of the Chisasibi Cree community, said the additional French proficiency requirements would force Cree youth who could not meet them to attend college in Ontario, farther away from their culture and communities. She called the Bill "an inconvenient and disrespectful obstacle for our nation to face when it comes to business, economic development, education, and attempting to strengthen our nation-to-nation relationship with Quebec" (Bell and Gunner 2022). Bertie Wapachee, chair of the Cree Board of Health and Social Services in the James Bay community, called it "another language that will again be forced on us" (Bell and Gunner 2022).

There is also the claim that Bill 96 puts an unfair burden on immigrants - they are required to communicate with the government and access government services in French after just 6 months. Even Quebecers who are generally in favor of the bill agree that the time frame is too short (Stevenson and Nakonechny 2022). More damningly, in 2019 Quebec's Immigration Ministry ordered a qualitative study, ostensibly to figure out what changes would need to be made to a government-funded French program in order to more effectively serve new arrivals "without a strong educational background" (Shingler 2022). The results of this study documented a range of challenges for new immigrants, from finding a place to live to dealing with the oft-traumatic events that pushed them out of their home countries. However, the report was never made public, its findings seemingly completely disregarded by the legislature in the drafting of Bill 96. Garine Papazian-Zohrabian, who led the study, condemned the six-month clause as "inhuman, and at the same time, it's also discriminating" (Shingler 2022).

Conclusion

The French language in Quebec has been tied to ethnic nationalism for nearly two centuries. While such nationalism initially developed as a way to preserve the French-Canadian identity in the face of a hostile government, it can still be found in Quebec even today. Although Canada has been independent for more than a century and a half, concerns about threats to the language have not abated. French, more than a means of communication, has become wrapped up in the struggle to define a cultural identity in an ever-changing world. In the process, however, efforts to protect French are veering dangerously close to the same type of linguistic repression they have historically tried to counter, threatening to render Quebec's current leadership no better than its former oppressors.

Bibliography:

Authier, Philip. 2023. “Quebec Has Reached Turning Point on Immigration Levels: Montreal Chamber.” Montrealgazette, September 20, 2023. https://montrealgazette.com/news/quebec/quebec-has-reached-turning-point-on-immigration-levels-montreal-chamber.

Bayley, Robert, and Schecter, Sandra, eds. 2003. Language Socialization in Bilingual and Multilingual Societies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Accessed November 10, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.binghamton.edu/lib/binghamton/detail.action?docID=236958

Bélair-Cirino, Marco. 2022. “La Réforme De La Loi 101 Du Gouvernement Legault Décortiquée.” Le Devoir, November 9, 2022.

https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/600986/presentation-de-la-nouvelle-loi-101.

Bell, Susan. 2022. “Indigenous Calls for Exemptions to Quebec’s Bill 96 Get Louder.” CBC, May 26, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/cree-inuit-education-bill-96-indigenous-languages-1.6465703.

Bell, Susan, and Stephane Gunner. 2022. “Cree Opposition Building in Northern Quebec to Bill 96’s Language Restrictions.” CBC, June 17, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/cree-bill-96-language-treaty-rights-indigenous-1.6490949.

Bill 96, An Act Respecting French, the Official and Common Language of Québec - National Assembly of Québec.” n.d. https://assnat.qc.ca/en/travaux-parlementaires/projets-loi/projet-loi-96-42-1.html.

Breton, Charles, Andrew Parkin, and Justin Savoie. “Quebecers More Pessimistic than Ever about the Future of the French Language.” 2022. Policy Options. June 27, 2022. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/june-2022/quebecers-more-pessimistic-than-ever-about-the-future-of-the-french-language/.

Canadian Heritage. “Some Facts on the Canadian Francophonie.” Canada.ca, 13 Sept. 2019, www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/official-languages-bilingualism/publications/facts-canadian-francophonie.html.

CBC. 2009. “Quebec Sees Growth in English-Speaking Population,” December 22, 2009. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-sees-growth-in-english-speaking-population-1.780246.

CBC. 2022. “Large Protest Held in Downtown Montreal against Quebec’s Controversial French-Language Bill,” May 14, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/protest-montreal-bill-96-1.6453557.

Charbonneau, François. “The Art of Defining Linguistic Minorities in Quebec and Canada.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 35, no. 1/4, 2017, pp. 493–511. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44983555 . Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

Cecco, Leyland. 2019. “Quebec Denies Frenchwoman Residency for Failing to Show Command of French.” The Guardian, November 9, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/08/quebec-denies-frenchwoman-residency-for-failing-to-show-command-of-french.

Cecco, Leyland. 2021. “Pardon My French: Dismay in Quebec as Francophones Fail Language Test.” The Guardian, April 8, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/06/quebec-language-requirement-test-residency.

Coleman, William D. “From Bill 22 to Bill 101: The Politics of Language under the Parti Québécois.” Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 14, no. 3 (1981): 459–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3230345 .

Educaloi. 2023. “Language Laws and Doing Business in Quebec | Éducaloi.” Éducaloi. June 5, 2023. https://educaloi.qc.ca/en/capsules/language-laws-and-doing-business-in-quebec/.

Fenwick, Rudy. 1981. “Social Change and Ethnic Nationalism: An Historical Analysis of the Separatist Movement in Quebec.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 23, no. 2 (1981): 196–216. http://www.jstor.org/stable/178733 .

Government Of Canada, Statistics Canada. 2022. “In Quebec, the Relative Proportion of Individuals Who Speak Predominantly French at Home Has Been Decreasing since 2001.” August 17, 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220817/g-a002-eng.htm.

Hall, Chris. 2021. “Why (Almost) Nobody in Ottawa Wants to Talk About Quebec’s New Language Bill.” CBC, May 28, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/bill96-quebec-language-legault-trudeau-blanchet-1.6043135.

Handler, Richard, Bernard Arcand, Ronald Cohen, Bernard Delfendahl, Dean MacCannell, Kent Maynard, Lise Pilon-Lê, and M. Estellie Smith. 1984. “On Sociocultural Discontinuity: Nationalism and Cultural Objectification in Quebec [and Comments and Reply].” Current Anthropology 25 (1): 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1086/203081.

Jonas, Sabrina. 2022. “Threat to French Language in Quebec ‘is a Myth,’ Says Canadian Party Leader at Campaign Launch.” CBC, August 31, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/canadian-party-of-quebec-1.6567686#:~:text=%22The%20idea%20that%20French%20is%20threatened%20in%20Quebec,decline%20in%20the%20French%20language%20in%20this%20province.%22.

Lampert, Allison, and Anna Mehler Paperny. 2022. “Analysis: Quebec Focuses on French-Speaking Immigrants as Companies Plead for Workers.” Reuters, June 13, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/quebec-focuses-french-speaking-immigrants-companies-plea-workers-2022-06-12/.

Latouche, Daniel. 1985. “JEUNESSE ET NATIONALISME AU QUÉBEC UNE IDÉOLOGIE PEUT-ELLE MOURIR ?” Revue Française de Science Politique 35, no. 2 (1985): 236–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43121410 .

Linteau, Paul-André. “UN DÉBAT HISTORIOGRAPHIQUE: L’ENTRÉE DU QUÉBEC DANS LA MODERNITÉ ET LA SIGNIFICATION DE LA RÉVOLUTION TRANQUILLE.” Francofonia, no. 37 (1999): 73–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43016993.

Lowrie, Morgan. 2022. “Setback for Quebec’s New Language Law as Judge Suspends 2 Articles of Bill 96.” CBC, August 12, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-judge-suspends-articles-1.6549844.

Marchand, Laura. 2022. “What’s in Quebec’s New Law to Protect the French Language.” CBC, May 24, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-explained-1.6460764.

Millette, Dominique. 2015. “Quiet Revolution.” n.d. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/quiet-revolution.

Ministère de la langue française, "Renversons la tendance." YouTube Video, 0:30. March 15, 2023. Ministère de la Langue française. 2023. “Renversons La Tendance.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVDofNbr80M .

Moldagazinova, Zhuldyz. 2019. “Trilingual Education in Kazakhstan: What to Expect - Voices on Cental Asia.” Voices on Cental Asia. May 24, 2019. https://voicesoncentralasia.org/trilingual-education-in-kazakhstan-what-to-expect/.

Oakes, Leigh, and Jane Warren. 2009. Langue, Citoyenneté et Identité Au Québec. Langue Française En Amérique Du Nord. Québec [Que.]: Les Presses de L’Universite Laval.

“Quebec | History, Map, Flag, Population, & Facts.” 2023. Encyclopedia Britannica. August 30, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/place/Quebec-province/Manufacturing#ref43138.

Ross, Selena, and Kelly Greig. 2022. “Quebec Lawmakers Vote on Amendments to Bill 96 as Its Final Passage Nears.” Montreal, May 12, 2022. https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/lawmakers-vote-on-bill-96-amendments-including-rules-for-cegeps-and-new-immigrants-1.5900079 .

Ross, Selena, and Joe Lofaro. 2022. “Language Law Bill 96 Adopted, Promising Sweeping Changes for Quebec.” Montreal, May 25, 2022. https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/language-law-bill-96-adopted-promising-sweeping-changes-for-quebec-1.5916503.

Rukavina, Steve. 2022. “Now That Quebec’s New Language Law Has Been Adopted, Many Wonder How It Will Be Enforced.” CBC, June 1, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-enforcement-1.6472094 .

Shingler, Benjamin. 2022. “Learn French in 6 Months? Quebec-Commissioned Report Shows Why That’s Nearly Impossible.” CBC, June 13, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-french-language-1.6483297.

Shingler, Benjamin, and Kate McKenna. 2022. “Quebec’s Election Campaign Has Just Begun, but Many Anglophones Already Feel Sidelined.” CBC, August 30, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-election-legault-caq-anglophones-english-1.6558678.

Stevenson, Verity. 2022. “Quebec Adopts Bill 96 French Language Reforms amid Concerns for Anglophone, Indigenous Rights.” CBC, May 24, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-vote-law-1.6463965.

Stevenson, Verity. 2023. “Quebec English Speakers Brace as Major Provisions of Language Law Come Into Effect.” CBC, June 1, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-major-provisions-into-effect-1.6861311.

Stevenson, Verity, and Simon Nakonechny. 2022. “What Do Rural Quebec Voters Think of Bill 96?” CBC, June 12, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/mauricie-region-bill-96-1.6486118.

The Canadian Press. 2021. “‘Breaking Point’: Studies Find French Language Is on the Decline in Quebec.” Montreal, March 30, 2021. https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/breaking-point-studies-find-french-language-is-on-the-decline-in-quebec-1.5367575.