The Effect of Female Genital Mutilation on Women and Their Communities in East Africa

Alexandra Pozo

About me

My name is Alexandra and I’m a student at Binghamton University. I’m a Biological Sciences major, on a Pre-Medicine track. I’m double minoring in Forensic Health and Global Studies. Currently, I’m thinking of adding on Africana Studies as a minor as well.

Traveling the world is the best way I could picture spending my time off from school. My favorite place to travel is Peru, the country that my mother and father grew up in. My interest in exploring other cultures began when I decided to spend the summer in Peru between ninth and tenth grade. I spent the summer helping my aunt sell clothes at the market and in return, on weekends we would explore. White water rafting, hand gliding, and traveling to the countryside gave me a better sense of self and strengthened my connection to my culture, however, it opened my eyes to the realities that lie beyond my own life experience. My perspective changed. Where I had previously seen happy pictures of families in a raft going down the river, I now saw the poverty that the workers lived in just so they could pay to use the river. I could see that I grew up in a sheltered world, one where my biggest struggle had been memorizing capitals in the US. Others less fortunate than me struggled for food and shelter.

From then on, I had a fascination with learning about different phenomena around the world. In my opinion, cultural competency is essential in any field, especially the one I wish to study, medicine. When I thought of this research, I knew I had found the topic that would pique my interest. Female genital mutilation is banned in the United States and most people here grow up either not knowing about it or not giving it a second thought. That’s exactly why I wanted to know more. It combines my passion for global studies and medicine since it is a cultural medical procedure. I love trying to wrap my mind around concepts that make me question my thoughts or even morals. As Westerners, we have no right to put opinions onto long-standing cultural practices that we will never understand. But, from what it seems, so many girls grow up to resent and denounce the practice, so should we make efforts to end its practice? That’s what I wanted to develop my own opinion on, after conducting mass research. So, what effect does female genital mutilation have on women and their communities in East Africa?

What is Female Genital Circumcision?

As social media and worldwide news coverage continue to take over the globe, we learn more about other cultures and traditions. Journalists can capture and spread the reality that may be difficult for an audience to understand or interpret. A tradition that comes to a shock for most of the Western world is Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C). The practice brings about very polarizing views. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting is the process of removing a part or whole of the female genitalia. The origins of the practice are speculated and there is no widely accepted origin story. While some believe that it began with the arrival of Islam in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa, others believe that it began during the slave trade when black women entered Arab societies. Ancient Egypt is the possible site of origin as fifth century BC circumcised mummies were discovered (Llamas, 2017). It does occur in the United States but it is illegal here. Statistics and research on the topic are not abundant because it generally occurs during childhood so numbers go unreported. Anti-human trafficking advocate, Joseph Chidiebere Osuigwe, stated: “To cut off the sensitive sexual organ of a girl is directly against the honesty of nature, a distortion to her womanhood, and an abuse of her fundamental human right” (DEVATOP, 2017). Others believe that female mutilation is a necessity so that a woman is fit to marry and see it as a right of passage (Alexander, 2020). Female mutilation has deeply-rooted cultural practices in Africa, the Middle East, and Asian countries. Generally, the collective and societal view in these regions is that female mutilation would prevent a girl’s promiscuity later in life. In Indonesia, it is a widespread belief that God wouldn’t accept the prayers of an uncircumcised woman. Accessibility is rampant in Indonesia, there are hospitals that offer female circumcision as a part of a “birthing package” which further legitimized the procedure (Alexander, 2020). Although female mutilation is justified by Islam, framing the practices as a religious tradition can promote Islamaphobia. The reality is that the Islamic religion does not condone female mutilation and the practices are recognized as outdated. Female mutilation takes place on cultural or traditional grounds, it is not done for medical reasons. Now it is a deeply rooted social norm that is rooted in gender inequality where violence against girls/women is widely socially accepted.

However, could we, as Westerners, ever truly understand the purpose and importance of female mutilation? I don’t believe that we could because everyone is a product of their own environment. In the USA, female mutilation is misunderstood because many people could never imagine mutilating one’s child in that way. However, male circumcision is a heavy practice and has become a norm in American society. The way literature is framed greatly influences our perception but language barriers and lack of cultural competence make it extremely difficult to find sources and support female mutilation.

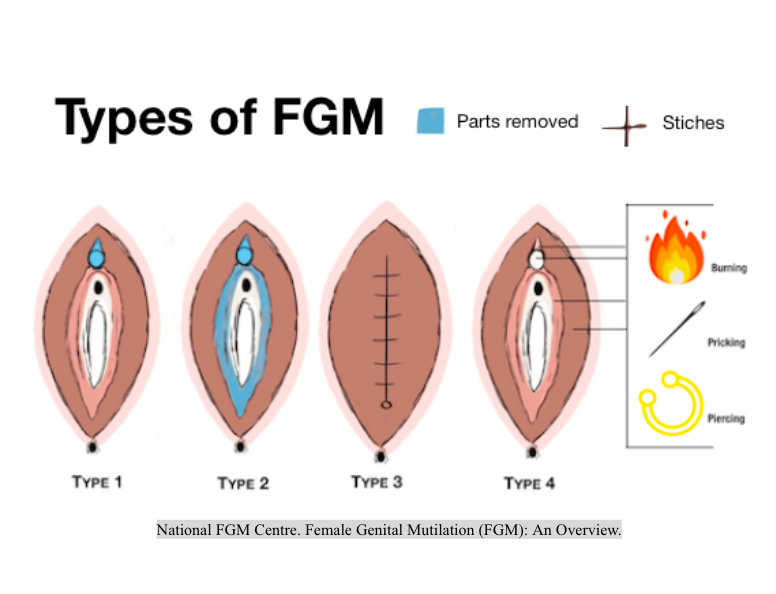

The procedure is generally done in unsanitary conditions which leads to a high risk of infection. The World Health Organization has classified four major types of female mutilation. Type I is when there’s partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and/or the prepuce/clitoral hood. The clitoral glans are the external/visible section of the clitoris that provides sexual pleasure, and the prepuce is the fold that surrounds it. Type II is the removal or partial removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (vulva’s inner folds), as well as the removal of the labia majora (vulva’s outer folds). Type III is also typically called infibulation which involves narrowing the vaginal opening with the creation of a covering seal by repositioning the labia minora/majora and cutting it. Lastly, Type IV includes the rest of the possible procedures done to the female genitalia for non-medical reasons like piercing, pricking, incising, scraping, and/or cauterization (World Health Organization).

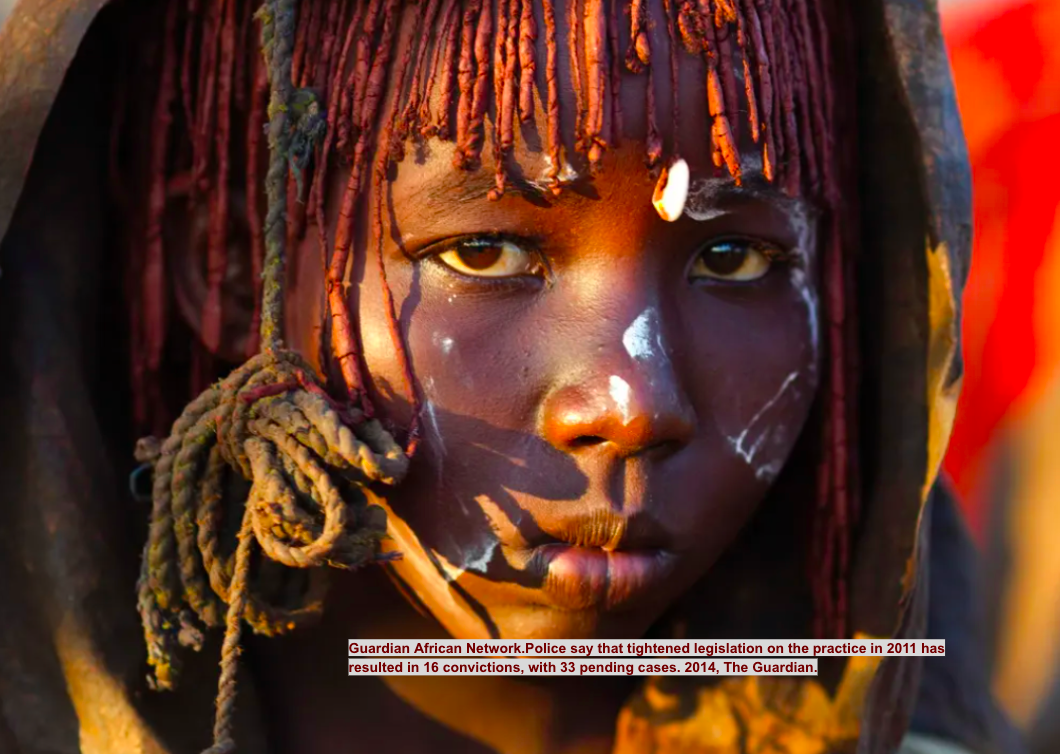

Circumcisor holding razors, commonly used to perform female mutilation

Circumcisor holding razors, commonly used to perform female mutilation

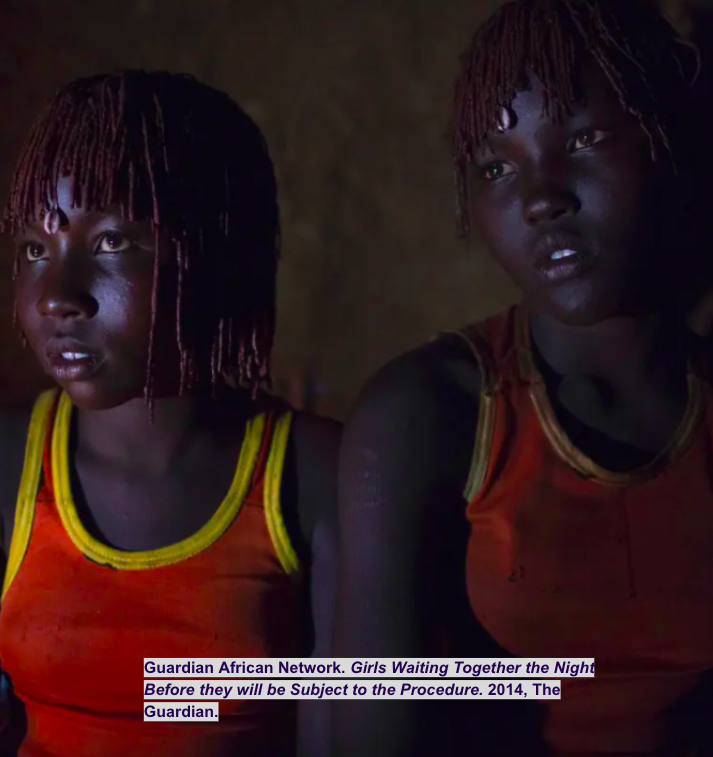

2 girls waiting together the night before undergoing the procedure

2 girls waiting together the night before undergoing the procedure

Rep. Mary Franson spoke in Minneapolis during a community education awareness meeting on female genital mutilation. To her right is FGM survivor Fadumo Abdinur

Rep. Mary Franson spoke in Minneapolis during a community education awareness meeting on female genital mutilation. To her right is FGM survivor Fadumo Abdinur

4 Types of FGM

4 Types of FGM

Prevalence:The Case in Kenya

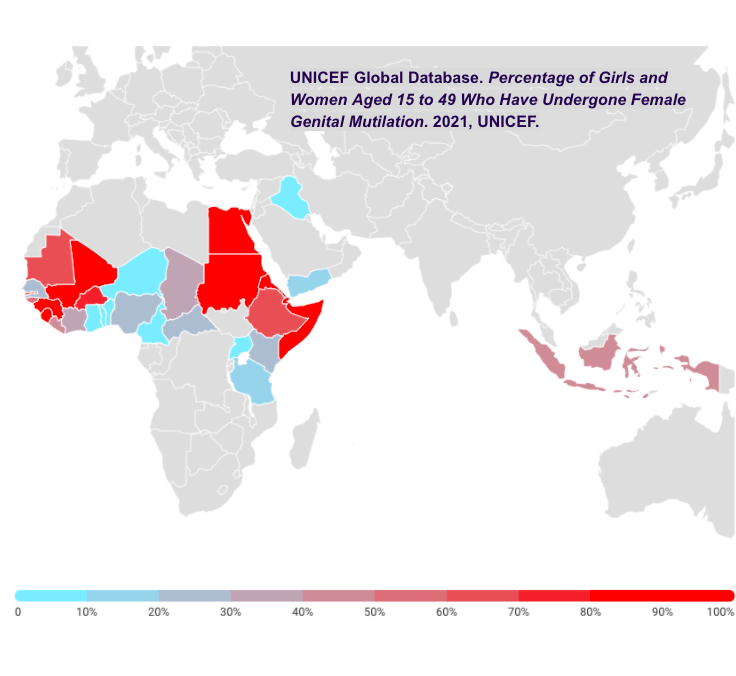

Percentage of Girls and Women Aged 15 to 49 Who Have Undergone Female Genital Mutilation

Percentage of Girls and Women Aged 15 to 49 Who Have Undergone Female Genital Mutilation

Prevalence: The Case in Kenya

According to the GLOBAL Revision of the World Population Prospects of 2017, Kenya has had 27% of girls/women aged 15 to 49 years old undergo the procedure. Traditional incisors make up the vast majority of performers of female mutilation (over 80%). Nurses, midwives, and other health care workers make up a small percentage of female mutilation performers (DHS, 2014). However, urban areas have higher rates of female mutilation performed by doctors compared to rural areas of Kenya due to access to healthcare. Growing concerns for human rights led to the criminalization of female mutilation in 2011. Punishment for performers or participants includes three years of imprisonment and a $2000 fine. The high court upheld the ban with a landmark ruling in 2021 in an attempt to eradicate the internationally condemned procedure. Even legal consequences did not put a stop however because it still runs rampant (Reuters, 2021).

The reasons why female mutilation is so prevalent are mostly social and economic. In many areas of Kenya, a family may be an outcast or shunned for not getting their girls circumcised. There is a huge amount of societal pressure imposed on the girls and their families to have the procedure done. The Kuria tribe is located close to the border of Tanzania and it has one of the highest rates of female mutilation. Families are often harassed by groups of armed men that go door-to-door to intimidate families into getting the girls circumcised. Community leaders are not completing their promise to put an end to the practice, leaving the townspeople feeling betrayed. High-level government officials and the Anti-FGM board visited Kuria to speak with the village chiefs and ask for cooperation, which was agreed upon. Shortly after the initial ban, the ceremonies were kept secret by taking girls early in the morning. But once there was a realization that nobody was going to stop them, the ceremonies became very public and full-blown once again.

Celebration hats are worn by girls who have just been circumcised as a sign. These girls were paraded openly in the streets while community members cheered, danced, and sang in celebration. The praise that the girls receive makes them feel accomplished and special. Although public celebrations are unchallenged by authorities, Kenya has been trying to reduce the prevalence by establishing a national Anti-FGM board, creating a reporting hotline, making a national roadshow program, and forming a team of twenty female mutilation prosecutors. Either way, rates tend to fluctuate because cutting will only happen in years that the elders see good omens.

Performers of female mutilation believe that there are health benefits in getting the procedure done but there aren’t. That is a myth, rather there are consequences. This belief however stems from the notion that female genitals are “dirty” and must be cut in order to become full, clean women as the girl ages (Desert Flower, 2018). Economically, a circumcised girl is beneficial because the family can get a higher bride price and have a higher status within the community (Horner, 2016).

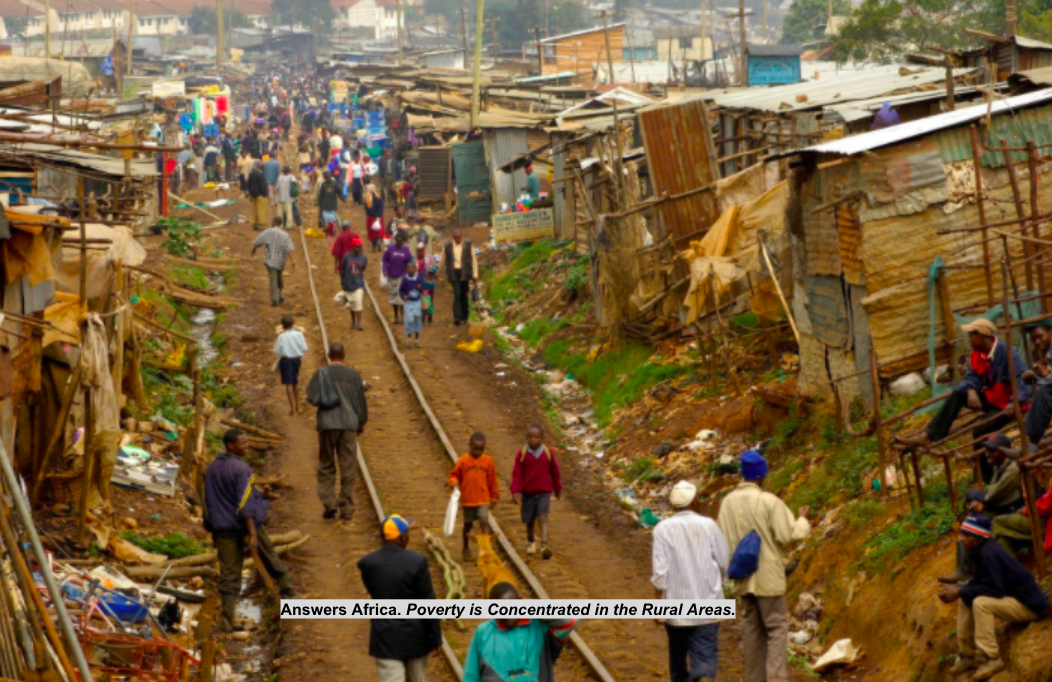

Crippling economy forces families to marry off their underage daughters

In Kenya, poverty is concentrated in rural areas

In Kenya, poverty is concentrated in rural areas

12-year-old Kenyan girl that was married to 2 men in the span of a month is carrying a baby

12-year-old Kenyan girl that was married to 2 men in the span of a month is carrying a baby

Crippling economy forces families to marrying off their underage daughters

The reality is that one-third of the population in Kenya is currently living under the poverty line, which is 15.9 million people poor. Looking beyond monetary poverty, the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics also measures multi-dimensionality poverty. To be considered to be living in multi-dimensionality poverty, you need to be deprived of at least three basic needs, rights, or services out of seven. “The basic needs are physical development, nutrition, health, education, child protection, information, water, sanitation, and housing. After analysis, the KNBS found that 53% of the population (23.4 million people) are multidimensionally poor (Wafula, 2020).

Families that are poverty-stricken offer their daughters as child brides as a means of knocking out certain living costs. By marrying off their daughter, there is one less person to feed, clothe and educate. Also, often the husband pays a dowry or a “bride price” that brings in income for those families in poverty. Younger girls are more likely to be married off because the older a girl gets, the more expensive the bride price becomes (Zarrilli, 2018). Girls that have undergone the procedure only increase the bride price higher (Horner, 2016). It makes sense that impoverished families would do what is necessary in order to survive. So, both child marriage rates and circumcision rates are high in sub-Saharan Africa. A population study has shown that the child marriage rate is about 54% in sub-Saharan Africa but there are large disparities ranging from 16.5% to 81.7% (Yaya, 2019).

However, marrying off young girls actually invocates an endless cycle of poverty. Girls that get married off, usually don’t get the opportunity to continue their education. Without education, it’s extremely hard to have economic growth in both the girl’s immediate and extended family. Child brides typically do a large amount of unpaid work at home like cleaning, cleaning, and caring for the family (children, husband, in-laws). So, they aren’t able to attend school. Even an extra year of primary school education for girls can improve future earnings by fifteen percent.

Internationally as well, child marriages have a big impact on economies. The World Bank and the International Center for Research on Women believe that in the year 2030, trillions of dollars will be the price to pay for child marriages since it perpetuates lack of education and the need to pay a “bride price” (Zarrilli, 2018).

Preservation of Virginity

Preservation of Virginity

Another huge reason for the prevalence of female mutilation is the belief that having the procedure done will preserve a girl’s virginity. In Western Africa, society dictates that in order to be wed, a girl or woman should be a virgin. If a girl has sex before marriage it is seen as a dishonor to the family. Girls who have sex during adolescence are even seen as dangerous. The age at first intimacy is an important indicator of risk for pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Currently, there is an AID pandemic in Africa. Increasingly important has become the trends of the age of first sex in order to determine and possible interventions targeted towards youth in order to reduce premarital sexual activity (Zaba, 2004). However, researchers have found that female circumcision has no association with outcomes of sexual behavior (Odukogbe, 2017). So, it seems that misinformation lies as a justification for the practice.

A population that is at potential risk of HIV transmission is the street-connected youth in Kenya. Even though it is an HIV endemic region, little is known about people’s perceptions of STIs. A study was conducted in Western Kenya on 65 participants to get firsthand accounts and experiences. It was found that the street youth in Western Kenya especially find sexually active adolescents dangerous. Miseducation about HIV only further perpetuates this idea. These ideas hurt the status of families just as being uncircumcised does. Girls who are uncircumcised are seen as less honorable and in practicing communities they are shunned. There have been instances where people will go as far as to refuse food prepared by an uncircumcised girl/woman and put curses on her and her family (National FGM Centre).

The concept of “defending the family’s honor” is only applied to girls because a boy’s honor is only his. This notion further perpetuates patriarchal values in society. Gossip, scandal, and shame are all tools used to control and dominate women, especially daughters and wives. Men on the other hand are allowed to behave autonomously and have the freedom to do as they would like. Feminine and masculine honor codes emphasize different values. While women accentuate chastity and conformity, men are supposed to be providers and protectors (Christianson, 2021). For women, any deviation from idealized sexual purity, modesty, decorum in dress, and discretion in social relations, is seen as a failure to act “correctly”. Restoring family honor is usually done by extreme corrections like honor violence. This type of violence can include social isolation, psychological/physical mistreatment, domestic violence, forced suicide, forced marriage, marital rape, and honor killing (Awwad, 2001). Honor violence is a problem worldwide that arises from gender-based and socio-economic inequalities (Bhanbhro et al., 2016).

16-year-old about to undergo virginity testing in a ceremony called Umhlonyana

16-year-old about to undergo virginity testing in a ceremony called Umhlonyana

Street children in Kenya

Street children in Kenya

Women in Lahore, Pakistan advocating for women's rights

Women in Lahore, Pakistan advocating for women's rights

From World Renowned Model to Award-Winning Activist

The Story of Waris Dirie

Young Safa Idress Nour who plays Dirie in her movie "Desert Flower" and who was saved from female mutilation by Dirie

Young Safa Idress Nour who plays Dirie in her movie "Desert Flower" and who was saved from female mutilation by Dirie

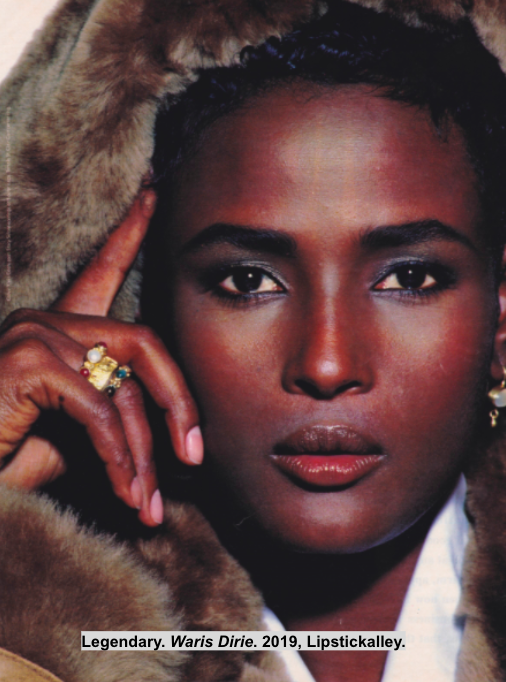

Headshot of Waris Dirie

Headshot of Waris Dirie

Waris Dirie accepting "Women of the Year Award Campaigning Award" for her work against FGM

Waris Dirie accepting "Women of the Year Award Campaigning Award" for her work against FGM

The Story of Waris Dirie

Waris Dirie’s story is a perfect example of how a survivor took it upon themselves to fight against those that oppressed them. She was a model who turned into an author and a Female Genital Mutilation advocate. Dirie was born into a 12 children household and the family lived near Somalia’s border with Ethiopia. During her childhood, she would tend to the family’s herd in order to earn enough food and water to survive.

Dirie underwent female mutilation when she was only 5 years old at the time. She really had no idea what the procedure was but her family spoke so highly and well of it, that she begged her father to have her do it. She experienced the most extreme form called infibulation, which is the process of having all or part of the external genitalia cut off and the vagina stitched up with only a small opening so that bodily fluids can be disposed of. The procedure was done under primitive and unsanitary conditions, also no anesthesia was used so she was forced to endure the terrible pain. Dirie states that she could barely walk afterward. Her sister also underwent the procedure but sadly bled out to death from the procedure (Britannica, 2021). At 13, Dirie ran away so she could avoid an arranged marriage to a man much older than her. At first, she embarked on a long and dangerous journey through the desert to get to Mogadishu, which eventually led her to London, England. In London, she served as a maid in the home of her uncle who was about to become an ambassador. Dirie stayed in London illegally after her uncle’s tenure was over. Since she was illiterate, she worked at a fast-food restaurant and took classes to learn how to read and write in English. When Dirie turned 18 in 1983, she was approached by a woman on the street who saw that she had a potential career in modeling. She went on to appear in runways in Paris, Milan, and New York; to advertise campaigns for Revlon and Chanel; and lead fashion magazines like Elle, Glamour, and Vogue. In 1995, her modeling career was chronicled by BBC in a documentary called “A Nomad in New York".

Eventually, she retired from modeling to focus on being an activist against female mutilation. In 2001, she founded the Desert Dawn Foundation so that she could raise funds for Somali clinics and schools. In 2002, she created the Waris Dirie Foundation so she could advocate for female mutilation abolition (Mantovani, 2019). She overcame many personal and cultural barriers along her path. Being that she had high celebrity status, female mutilation really came to the forefront. The United Nations Population Fund appointed her as the special ambassador for the elimination of female mutilation in 1997. Dirie then traveled and spoke about how her goal is to prevent future generations of women from undergoing the pain and suffering that she did as a result of female mutilation. She believes that legislation is not enough to stop the practice, rather countries must be actively working to end female mutilation. Dirie’s story is just another example of how some modern-day women and girls want to abandon this long-standing cultural practice.

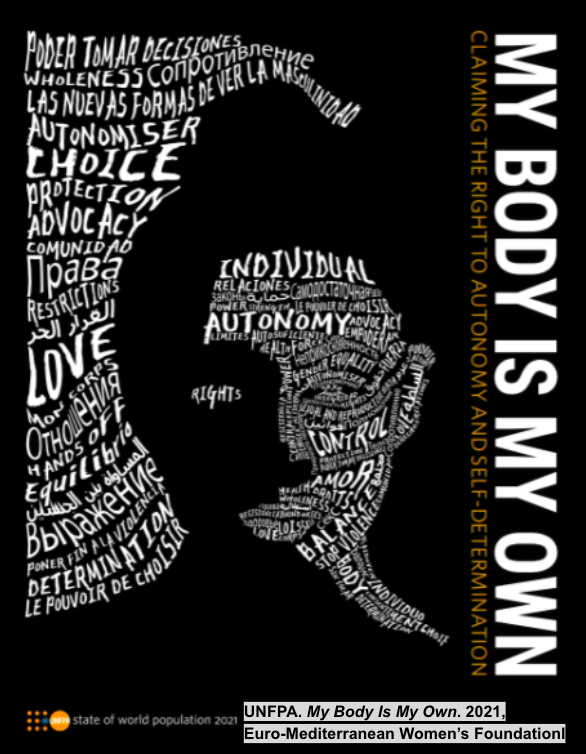

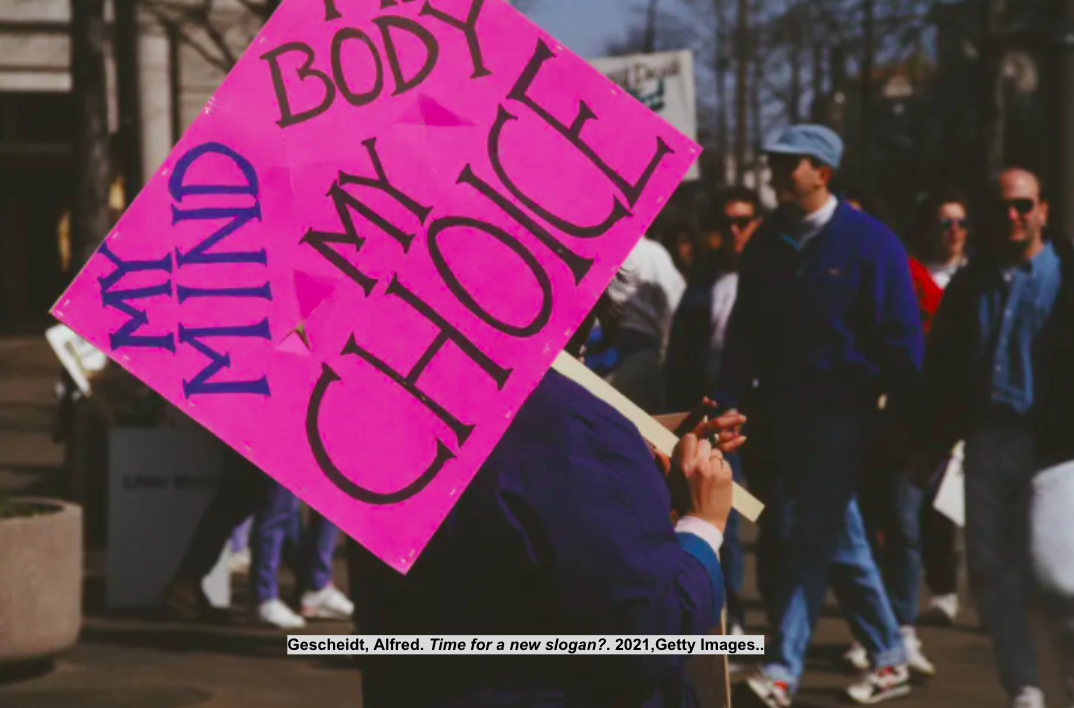

Is Female Mutilation a Breach of Body Autonomy?

Body Autonomy

One of the biggest arguments against female mutilation is the notion that it doesn’t allow girls bodily autonomy. Sometimes girls are tricked or forced into the procedure. Just as Waris Dirie mentioned, her family members acted as if female mutilation was a great accomplishment, this lead Waris to ask her parents to have the procedure done when she was only five years old (Britannica, 2021). Female autonomy is a human right but it is often disputed and disregarded at the hands of the men that government our countries.

Violations of bodily autonomy prevent women from having the ability to make decisions about their own bodies. A report has shown that in the countries where data was available, only 55% of women are empowered to make choices regarding healthcare, contraception, and the ability to say yes or no to sex (UNFPA, 2021). Body autonomy is only restricted when it comes to women and girls. 20 countries/territories around the world have “marry-your-rapist” laws, in which criminal prosecution for a rapist will be avoided if he married the girl/woman he has raped. While over 30 countries limit women from moving around outside of their homes. Men and boys do not have restrictions like this. Denying one of body autonomy perpetuates the inequality of women and maintains violence against women in the name of discrimination.

Is female mutilation a violation of bodily autonomy? It’s difficult to say really. In some regions it is done for girls that are 2 or younger, in that case, it is a violation of bodily autonomy because the girls cannot consent to a procedure like that yet. They do not know the consequences and the real-life traumatic experiences that can come with it. An adult woman can consciously consent but some people believe that they are “brainwashed” into wanting the procedure by environmental pressure. The reality is that everyone feels pressure to behave a certain way, and who are we (as Westerners) to say where the line must be drawn. This is especially true considering that efforts to end female mutilation have been grounded in conversion to Christianity, so these efforts could seem ingenuine. Moreover, efforts are being made to only prevent the practice, much less on aiding patients with health complications from female mutilation (Khosla, 2017). One will never truly be able to understand another culture without spending years embedded in it. It would be very difficult to look at it as black and white.

Cover of a report that highlights bodily autonomy that is popular in Africa

Cover of a report that highlights bodily autonomy that is popular in Africa

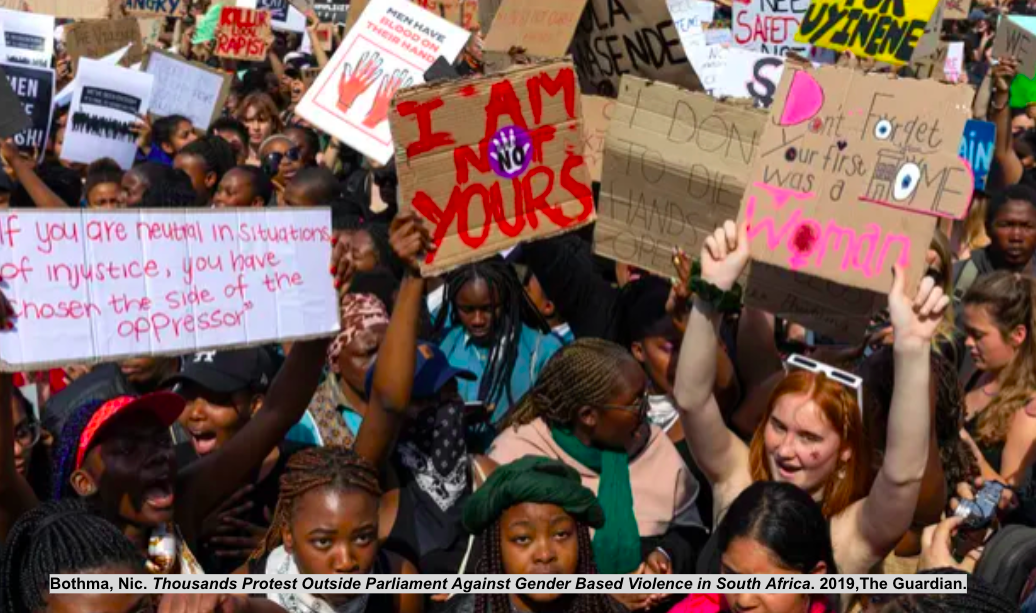

Women protest against rising violence against women

Women protest against rising violence against women

Protestor holding up a sign in support of women's bodily autonomy

Protestor holding up a sign in support of women's bodily autonomy

The Reality of Female Genital Mutilation

Consequences

Family mourning after the death of Fartun Hassan Ahmed from Somalia, which bled to death after undergoing female mutilation

Family mourning after the death of Fartun Hassan Ahmed from Somalia, which bled to death after undergoing female mutilation

6-year-old girl screaming as she is undergoing female genital mutilation

6-year-old girl screaming as she is undergoing female genital mutilation

Gynecological surgeon Dr. Marci Bowers conducting a clitoral restoration in Nairobi, Kenya

Gynecological surgeon Dr. Marci Bowers conducting a clitoral restoration in Nairobi, Kenya

Midwifery students studying how to deal with the complications caused by female genital mutilation at the Hargeisa Institute of Health Sciences

Midwifery students studying how to deal with the complications caused by female genital mutilation at the Hargeisa Institute of Health Sciences

Consequences

Practitioners of female mutilation have poor surgical skills making the procedure dangerous, to begin with. Additionally, they do not use antiseptic techniques and do not use anesthetic agents which leads to several complications. The damage may occur while the operation is happening or immediately after, but could lead to long-term ramifications. Poor quality of life or mortality can be consequences of female mutilation. Excruciating pain for one is immediate for the patient, among hemorrhage, shock, acute urinary retention, and injury to adjacent tissue. 185 studies across 57 countries have found that the most common immediate complications were urine retention, excessive bleeding, and genital tissue swelling. Infections of the reproductive tract are medium-term complications that come from using unsterilized instruments, septic environment, septic techniques, and raw wound surfaces. These techniques can result in urinary tract infections, pelvic inflammatory diseases, chronic pelvic pains, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, tetanus infections, hepatitis infections, human immunodeficiency viruses, and abscess formations.

Those that survive medium-term consequences may experience long-term consequences. These include psychological disturbances, low libido, apareunia or dyspareunia, chronic pain, dysmenorrhoea, synaesthesia, cryptomenorrhoea, vaginal fistulae, labial agglutination, hypertrophic scar/keloids, clitoridal retention cysts, dermoid cysts, vaginal lacerations during coitus, straining at micturition, genital tract lacerations, obstructed labor, increased rate of cesarean delivery and postpartum hemorrhage. Mortality can still happen after however. Stillbirth and early neonatal death rates are increased as well as babies with neurological deficits from severe birth asphyxia if birthed by circumcised women. Sexual arousal such as the attainment of orgasm and sexual satisfaction is put severely at risk since the clitoris is sometimes removed during certain types of circumcision.

While the best management is to avert the procedure, if it did occur then management would be patient-specific. If a patient is hemorrhaging, restoring the body’s cardiovascular volume with crystalloids, blood, and blood products while administering supplemental oxygen was crucial to limit any medium to long-term complications. For infections, microscopy tests were run on wound swabs so the patient could be treated with potent antibiotics. To control pain or acute urinary retention, urethral catheterization with analgesics is helpful. At the community level, creating emergency care and improving health care services in areas where female mutilation runs rampant could prove helpful.

Referrals to sex therapists and/or psychotherapy have proven to be effective in positively changing the patient’s life. This is because female mutilation deprives women of sexual gratification as well as a right to sexual pleasure, which is needed to achieve full psychophysical well-being. Reduction of sexual desire, arousal, excitement, orgasm, and dyspareunia has been reported to be problems for circumcised women. Sexual dissatisfaction in circumcised women is really dependent on what type of circumcision they have undergone. Those with types II, III, and IV are at a higher chance of having increased sexual dissatisfaction due to lower levels of sexual functioning, decreased arousal, vaginal dryness, and painful orgasm, and lower overall satisfaction compared to those with type I female genital mutilation. Also, negative genital image and sexual dysfunction are more common in a woman that has undergone type II, III, and IV female circumcisions (Krause et al., 2011). Psychosocial consequences consist of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, panic disorders, inhibition, depression, suppression of feeling/thinking, and suicidal tendencies (Abdel-Azim, 2013). These effects can come from the painful procedure itself or the sense of humiliation, feeling of betrayal by parents, use of force to have the procedure done, negative genital image, feeling of loss of bodily autonomy, the devastation of sexual life, or infertility that could develop after (World Health Organization, 2018).

The reproductive health of circumcised women is also at risk. Pelvic infections or coital problems can cause infertility. Even if these women do get pregnant, the circumcision puts them at high risk of having obstetric complications (Vita et al., 2016). As the type of female genital mutilation goes up, the severity of the risk increases, risks are not limited to postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomies, perineal lacerations, cesarean deliveries, stillbirth, or neonatal death. Type III female genital mutilation (infibulation) can cause an obstructed labor or vaginal/vulval laceration. Defibulation may be performed on women who have infibulation during the time of delivery (Rouzi, 2001). Health complications for newborns in Gambia are four times more likely if birthed by a mother with female mutilation.

Bibliography

Abdel-Azim, S. (2013). Psychosocial and sexual aspects of female circumcision. African Journal of Urology, 19(3), 141-142.

Alexander, L. (2020, May 11). Female Genital Mutilation in Southeast Asia. Retrieved from https://borgenproject.org/female-genital-mutilation-in-southeast-asia/

Awwad, A. M. (2001). Gossip, scandal, shame and honor killing: A case for social constructionism and hegemonic discourse. Social thought & research, 39-52.

Bhanbhro, S., de Chavez, A. C., & Lusambili, A. (2016). Honour based violence as a global public health problem: a critical review of literature. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, June 9). Waris Dirie. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Waris-Dirie

Christianson, M., Teiler, Å., & Eriksson, C. (2021). “A woman’s honor tumbles down on all of us in the family, but a man’s honor is only his”: young women’s experiences of patriarchal chastity norms. International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being, 16(1), 1862480.

DEVATOP. (2017, August 6). 7 Quotes About Female Genital Mutilation by Joseph Osuigwe Chidiebere. Retrieved November 24, 2021, from https://www.devatop.org/7-quotes-about-female-genital-mutilation-by-joseph-osuigwe-chidiebere/

Horner, R. (2016, December 23). FGM in Kenya:’Girls are being paraded openly in the streets’. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/dec/23/fgm-in-kenya-girls-are-being-paraded-openly-in-the-streets

Khosla, R., Banerjee, J., Chou, D., Say, L., & Fried, S. T. (2017). Gender equality and human rights approaches to female genital mutilation: a review of international human rights norms and standards. Reproductive health, 14(1), 1-9.

Krause, E., Brandner, S., Mueller, M. D., & Kuhn, A. (2011). Out of Eastern Africa: defibulation and sexual function in woman with female genital mutilation. The journal of sexual medicine, 8(5), 1420-1425.

Llamas, J. (2017, April). Female Circumcision: The History, the Current Prevalence and the Approach to a Patient. Retrieved November 24, 2021, from https://med.virginia.edu/family-medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/285/2017/01/Llamas-Paper.pdf

Mantovani, C. (2019, March 7). Model turned activist Waris Dirie says world is ignoring the crime of FGM. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-women-rights-fgm/model-turned-activist-waris-dirie-says-world-is-ignoring-the-crime-of-fgm-idUSKCN1QO22X.

Odukogbe, A. T. A., Afolabi, B. B., Bello, O. O., & Adeyanju, A. S. (2017). Female genital mutilation/cutting in Africa. Translational andrology and urology, 6(2), 138.

Project, B. (2019, November 05). The Effects of Child Brides on Poverty & the Benefits of Abolishment. Retrieved from https://borgenproject.org/the-crippling-effects-on-poverty-of-child-brides-and-the-benefits-of-abolishment/

Reuters. (2021, March 17). Kenya dismisses challenge to its ban on female genital mutilation. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kenya-women-fgm/kenya-dismisses-challenge-to-its-ban-on-female-genital-mutilation-idUSKBN2B9239

Rouzi, A. A., Aljhadali, E. A., Amarin, Z. O., & Abduljabbar, H. S. (2001). The use of intrapartum defibulation in women with female genital mutilation. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 108(9), 949-951.

UNFPA. (2021, April 14). Nearly half of all women are denied their bodily autonomy, says new UNFPA report, My Body is my own. GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.globenewswire.com/fr/news-release/2021/04/14/2209611/0/en/Nearly-half-of-all-women-are-denied-their-bodily-autonomy-says-new-UNFPA-report-My-Body-is-My-Own.html.

Vital, M., de Visme, S., Hanf, M., Philippe, H. J., Winer, N., & Wylomanski, S. (2016). Using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to evaluate sexual function in women with genital mutilation undergoing surgical reconstruction: a pilot prospective study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 202, 71-74.

Wafula, P. (2020, August 12). Kenya: Sad Reality of 23.4 Million Kenyans Living Below Poverty Line. Retrieved from https://allafrica.com/stories/202008120697.html

World Health Organization. (2018). Health risks of female genital mutilation (FGM). Accessed on, 20(8), 16.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Types of female genital mutilation. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-(srh)/areas-of-work/female-genital-mutilation/types-of-female-genital-mutilation

Yaya, S., Odusina, E. K., & Bishwajit, G. (2019). Prevalence of child marriage and its impact on fertility outcomes in 34 sub-Saharan African countries. BMC international health and human rights, 19(1), 1-11.

Zaba, B., Pisani, E., Slaymaker, E., & Boerma, J. T. (2004). Age at first sex: understanding recent trends in African demographic surveys. Sexually transmitted infections, 80(suppl 2), ii28-ii35.

5 Myths about FGM. (2018, January 25). Retrieved from https://www.desertflowerfoundation.org/en/news-detail/id-5-myths-about-fgm.html