The Creation of Culture on London's Transportation

How will an increase in active travel in England affect the cultural encounters that occur in the space of shared transportation?

Title image courtesy of Kate Hill (Hill, 2019).

INTRODUCTION

One night while I was in London, my friend and I were riding the tube from the West End to Shoreditch. The train was far from full, just us and a few other passengers spread out within the car. Across from us were two men, one of whom was eating a container of Isu soup that had an aroma that was filling the train. An older passenger enters the train a stop after we had, and makes a comment acknowledging the soup and it’s delicious scent. This begins a lively conversation among all of the passengers in the car. The man eating the soup responds in an American accent, which inspires my friend and I to interact with him and find out where he is from. When we discover he is from the east coast as well, we further marked our identities on the train as Americans in England. Our creation of a smaller group within a larger culture (Americans living in London), or a subculture, on that train marked every other passenger as an other (not an American living in London), and forced them to self-categorize as non-American in juxtaposition to our category of American. In response to our creation of subculture on the train, different passengers shared stories of their origins and some younger English passengers spoke of their travels to America.

Social scientist Goffman’s civil inattention rule of behavior, which is generally followed in the space of shared transit, states that “people show that they have noticed each other, but immediately afterwards they draw their attention away to show that they don’t see the other person as weird or special” (Soenen 2006, 3-4). The civil inattention rule is explained further in the Audiopedia video attatched in the following section. While the older gentleman first broke the civil inattention rule, the conversation quickly became one among the younger generations on the train, creating yet another subcultural group within the confined space of the train. Once we exited the train at our stop, the private relationships that we had formed briefly on the tube ceased to exist and remained just a singular experience on the tube, but an important one that allowed us to participate in and shape the culture of London during our brief trip to Shoreditch.

Recently, there’s been a push in England towards modes of active travel. These consist of methods of transportation that are better for both the body and the environment, such as walking or biking. In recent years, active travel has been preferenced by various political policies. For example, “successive Mayors have launched initiatives both to encourage cycling (e.g. a bicycle sharing system)” as well as policies to “discourage driving (e.g. the introduction of a 'congestion charge' for cars entering central London)” (Goodman 2013, 1). Additionally, England has implemented a Cycle to Work scheme that provides a tax-free bicycle to workers with savings between 25 and 39%. This scheme has been utilized by hundreds of thousands of workers (Busca 2016). The amount of people who cycle to work more than doubled between 2001 and 2011 (Office for National Statistics 2014, 3), so clearly the policies pushing for increasing active travel are being met positively.

If I had been walking or cycling to Shoreditch that day, would I have been able to participate in and produce the same cultural encounters? How will an increase in active travel (walking or cycling) in England affect the cultural encounters that occur in the space of shared transportation?

Will people be less likely to socialize while cycling than when riding on shared transit (Court 2018)?

Will people be less likely to socialize while cycling than when riding on shared transit (Court 2018)?

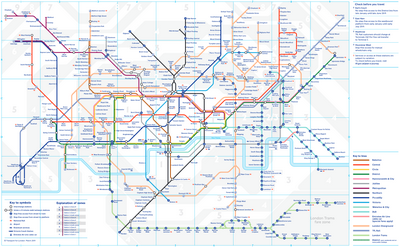

A map of London's Underground Tube System (Transport for London 2020).

A map of London's Underground Tube System (Transport for London 2020).

Civil Inattention explained by The Audiopedia (Audiopedia 2017).

A rainbow double-decker bus in London celebrating LGBTQ+ pride (Hoscik 2015).

A rainbow double-decker bus in London celebrating LGBTQ+ pride (Hoscik 2015).

THE SOCIETAL REALMS OF LONDON’S SHARED TRANSIT

The shared space of transportation, such as busses and the tube, is hard to define culturally. Since it is a shared confined space where strangers are forced to interact with one another, the space inherently creates “coprescences” (Goffman 1963, 17) between strangers that make it difficult to describe as within the social or private realm of society. These copresences, however, are within range of one another, meaning that “the physical distance over which one person can experience another with the naked senses” is shortened on public transit (Goffman 1963, 17). While the copresences of strangers within range limits the ways in which shared transit can be seen as private, it is also difficult to describe transit as within the public realm since people’s social lives are brought onto transit when groups of people ride together and private lives regularly overlap into the shared space through phone calls or conversations that are overheard by strangers (Soenen 2006, 4). The space is also government owned and requires an entry fee in the form of a ticket to enter the space. Additionally, strangers can form alliances in the face of a disruption to routine or in opposition to one another (Soenen 2006, 6). Although these connections most commonly end when one unknown passenger leaves the moving space, there is a potential for the link to grow into a closer relationship.

The space of transit is one where people’s private lives are brought into the public realm and “cross the traditional boundary between private behaviour in private space...and public behaviour in public space on the other” (Soenen 2006, 5). Thus, the shared space of transportation may best be defined as both public, as it is most commonly used that way, but additionally pre-private, as it inherently allows for the development and inclusion of private insights and relationships. In this sense, a pre-private environment is one that includes a platform for established private relationships to perform their relationship, as well as the potential for new private relationships or private encounters to form.

These relationships and interactions with one another foster community and diversity within a metropolitan like London. London’s use of shared transportation spans across different ages, races, backgrounds, and destinations. With a push towards transport only occurring in the public and non-confined space of the outdoors, there is a potential for these subcultural encounters to become limited and the communities within the diverse city of London to become further segregated from one another.

The interactions between different subcultures fosters the creation of community and sub-community in the moving space of public transit. Historically, it has been proven that “life-style groups are relevant behavioral groups which share relatively similar tastes in the choice of mode and destination for shopping trips” (Saloman 1983, 13). The mode one chooses to use for transit, in this case specifically for shopping trips, therefore indicates something about their class background and marks them as within a specific sub-community of London, even if said sub-community is simply those who take busses to the grocery store. Within that sub-community, there are different genders, ages, and educational backgrounds that meet in the shared space of transit.

Taking that into consideration, there are of course different lifestyles and classes that choose to take the underground or overground to work instead of driving in the difficult to park in and full of traffic metropolitan areas of London. For example, the relatively new above-ground tube system in London, the London Overground, cited in 2013, three years after its development, that 64% of its users were traveling to or from their workplace (The Economist 2013, 33). Of those going to work, there are various different jobs one could be traveling to, with different lifestyles and identifying factors.

Amid the Coronavirus, Transport for London began reserving some bus routes solely for children on their way to and from school (Transport for London 2020). Since Transport for London assumed it financially worthwhile to reserve these bus routes primarily for students, it can be assumed that a large proportion of bus-riders in the reserved times are school-aged. As is the same for workers, this creates a provincial community of students. Whether or not students who ride shared transit know one another, attend the same schools, or even take the same routes, they share the identity of a school-aged transit rider. When easily excited students bring social life into the space, raise noise-levels are raised, and/or create conflict in the confined space of public transit during these specific times of day (Soenen 2006, 4), other riders know to relate this shift to the students within the shared spaces, so that the school children, who may or may not know each other across different routes, backgrounds, and schools, are grouped together as one kind of passenger: students who ride public transport between X and Y hours. They then interact with other subgroups (ex.: workers from X neighborhood, people on their way to visit lovers, mothers on the phone with husbands, toddlers who are eager to meet new people. etc.) and further mark themselves in relation to the other.

Additionally, colleagues who ride the train together may further identify as workers from their company in contrast to workers in the shared space from other companies. In these instances both the students and workers are both actively creating cultural identifiers and then interacting with members of other subcultures. It would be very hard to imagine cycling or walking providing the same opportunities for social encounters as mass transit does with its confined shared spaces.

PRE-PRIVATE ENCOUNTERS ON LONDON’S SHARED TRANSIT

Not only does identifying one’s subculture through private interactions in the public realm of shared transit create the aforementioned pre-private atmosphere, but so does the public’s response to these private encounters. Goffman’s civil inattention rule can be broken in response to a change of routine or a positive conversation starter. In Soenen’s research about the space of transportation in the western world, she found that the factor most likely to force strangers within range of one another to break Goffman’s civil inattention rule was the presence of children or dogs (Soenen 2006, 4). Likewise, issues with transit or disorganization may force copresent strangers to work together, a rude or negative person on the transit could encourage strangers to exchange knowing looks, or other small eruptions on the confined space may also force copresent strangers to interact. For example, “the conversations of small groups can also cause laughter amongst strange bystanders and create a temporary social atmosphere” (Soenen 2006, 5). This is how the civil inattention rule was broken on my train ride to Shoreditch.

Since the civil inattention rule is always followed with the potential to be broken, the shared transit spaces always have the potential to become social and create private relations and thus always exist in a pre-private state. In addition to the creation of relationships when the civil inattention rule is broken, the private and public realms also interact when people bring their personal and private encounters onto the shared transit (Soenen 2006, 4-5). When a couple argues, or expresses public displays of affection, or marks themselves as a couple in any way in the shared space, they are displaying their private life. If a mother calls her daughter and recites a grocery list while on the bus, she is redefining the boundaries of the public space through virtual interactions with her private life.

Sadiq Khan implemented new policies to increase diversity on shared transit (Taylor 2016).

Sadiq Khan implemented new policies to increase diversity on shared transit (Taylor 2016).

Contrary to shared transit, "London's cycling chief has claimed the capital's biking community faces a diversity problem" (Willis 2018). Many cyclists are middle class white men like those in this photograph (Selwyn 2018).

Contrary to shared transit, "London's cycling chief has claimed the capital's biking community faces a diversity problem" (Willis 2018). Many cyclists are middle class white men like those in this photograph (Selwyn 2018).

This photograph, along with the underlying caption, was found on visitbritian.com in an article titled Tube etiquette: top 9 tips for travelling on the London Underground (Visit Britain 2020).

This photograph, along with the underlying caption, was found on visitbritian.com in an article titled Tube etiquette: top 9 tips for travelling on the London Underground (Visit Britain 2020).

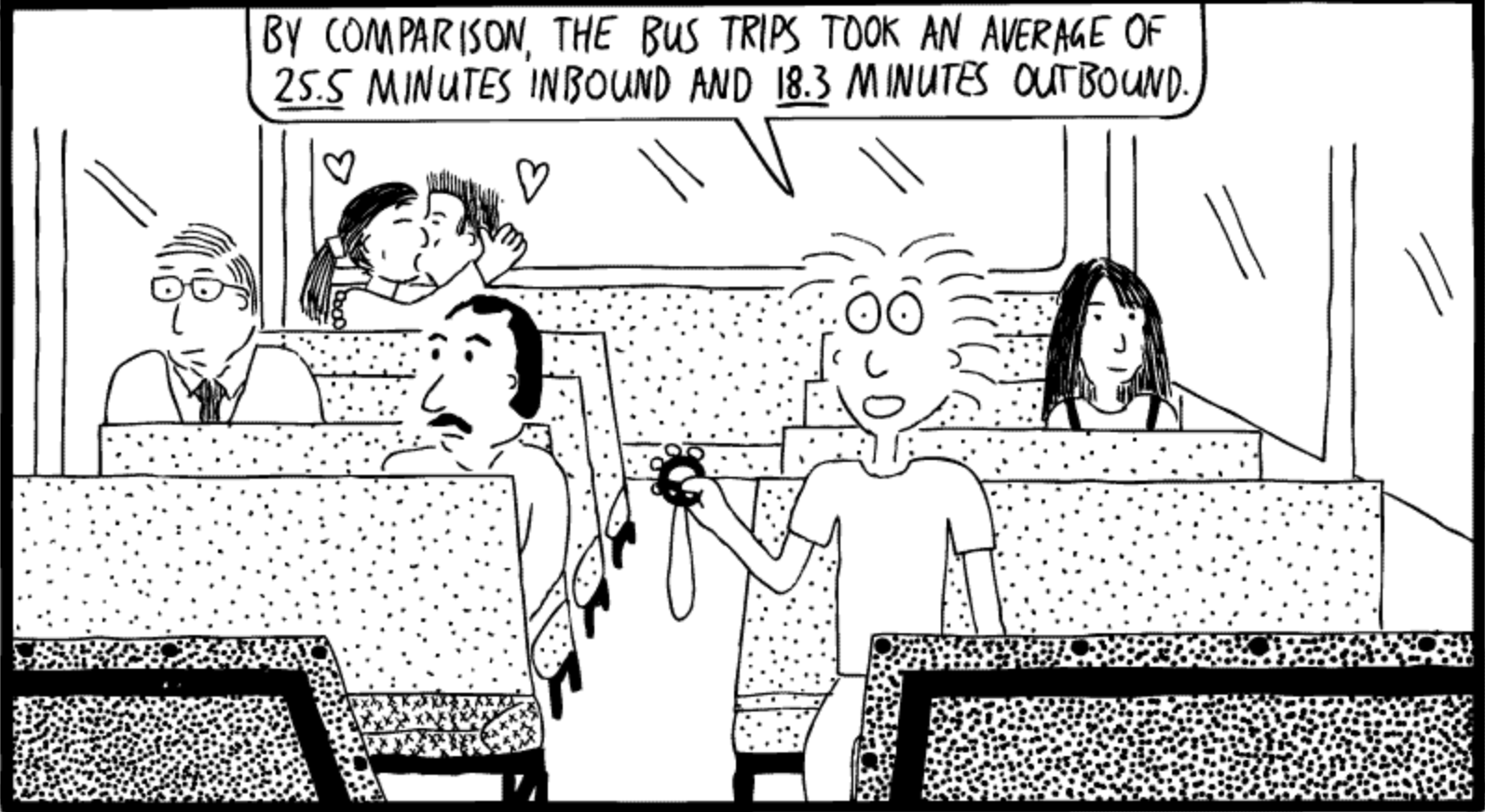

Comic artist, Stuart McMillen, found in 2009 in Brisbane that it was faster for them to cycle to work than to take the bus. However, in his depiction of the bus he includes a couple crossing the boundary between private and public realms (McMillen 2009).

Comic artist, Stuart McMillen, found in 2009 in Brisbane that it was faster for them to cycle to work than to take the bus. However, in his depiction of the bus he includes a couple crossing the boundary between private and public realms (McMillen 2009).

REPRODUCING CULTURE ON LONDON’S SHARED TRANSIT

Overall, “micro spaces tend to be semi-public and stimulate diverse groups to intermingle, which results in on – off as well as repetitive and structural interactions” (Peterson 2016, 1). In other words, the confined space of the shared transit forces culture to constantly be reproduced and identity to be reperformed routinely and structurally throughout the day. Not only that, but it also forces members of different subcultures to visualize other subcultures and, in light of breakage of the civil inattention rule, interact in response to small disruptions to the transit ride. If less people opt to take shared transit and instead begin to walk or bike, the ways in which people socialize and interact -- and by extension how culture is reproduced -- will inherently change as these conversations are not given a stage to be acted out upon. Thus the ways one marks themselves, as well as the other, will change alongside that.

LONDON’S SHARED TRANSIT AS A BRITISH EXPERIENCE

Furthermore, the experience of shared transit in London is unique to London. Each city interacts with their shared transit in a different way. Despite different backgrounds and subcultural groups utilizing London’s transit, all must do so in a British way in order to not cause a small disruption within the space. While the conversations between friends or couples on the phone or in person on shared transit define the intersections between private and public life within the shared space, they would, in my experience, be unwelcomed in the quieter transit of Paris.

The public performance of private lives and those accepting it as a cultural norm marks each passenger as a member of British culture at the time of the transit ride. In research done on well educated Taiwanese people traveling to New York City, they were shocked at the norms of transit in New York, asking “How could the subways in the Big Apple, presumably the pinnacle of Western modernity, be so shabby and disorderly?” (Lee 2007, 38). The answer, of course, is that the acceptance of the norm and the consequential performance of that norm is entirely culturally dependent. Therefore, the entirety of shared transit culture marks a British identity to all those who use it, creating an important subculture simply through its existence.

The standard double-decker bus has become an icon for London life and a popular photo-op and souvenir theme for tourists (Visit London 2020).

The standard double-decker bus has become an icon for London life and a popular photo-op and souvenir theme for tourists (Visit London 2020).

Double-decker buses have become symbolic of London life and are popular for souvenirs (Amazon 2020).

Double-decker buses have become symbolic of London life and are popular for souvenirs (Amazon 2020).

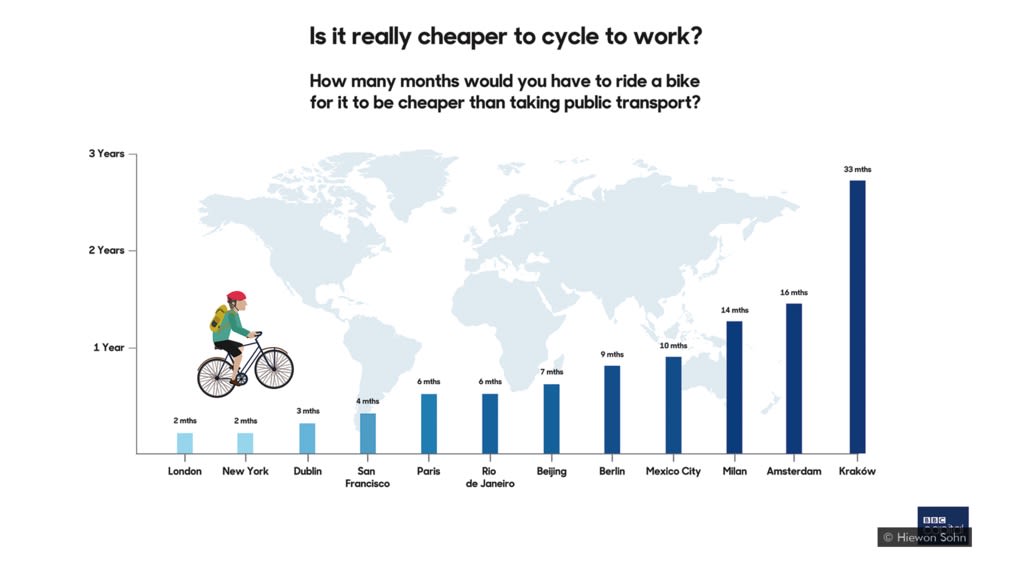

In London, it pays to switch to active travel. After just two months, workers will begin to save money from cycling (Sohn 2016).

In London, it pays to switch to active travel. After just two months, workers will begin to save money from cycling (Sohn 2016).

The Oyster Card is London Underground's contactless payment method (Visit London 2020).

The Oyster Card is London Underground's contactless payment method (Visit London 2020).

EXISTING EXCLUSION FROM LONDON’S SHARED TRANSIT

My hometown, Buffalo, NY, is the third poorest (Wozniak 2007) and sixth most segregated city in the US with a population over 250,000 (Heaney 2020). As an American from Buffalo who has frequently used public transportation, it is apparent to me that socioeconomics play a large role in one's use and experience of mass transit. For example, the same year that The Economist reported that 64% of the London Overground’s passengers were workers, The Independent theorized about the future of a cashless London (Beanland 2014). If this theorized future were ever to come to fruition, which is already an increasing reality through the employment of cashless Oyster Cards and debit cards on bus routes in England, it would limit the accessibility of public transportation to London’s exceptionally large population of homeless people (Fransham 2018, 1), as well as to children who don’t yet have access to cashless options without the aid of their parents.

A spatial analysis of customer satisfaction with bus routes in London found that “mean values of overall satisfaction were highest in the least deprived neighbourhoods and lowest in areas with higher social deprivation” (Grisé 2017, 174). Similarly, a study on the spatiotemporal dimensions of transport found that “night-time workers face severe accessibility barriers, often relying on low-frequency bus services that have inadequate service coverage across Greater London” (McArthur 2019, 433). Of course, customer satisfaction is a subjective measurement, which the authors acknowledge. The findings of their study use data from Transport for London’s customer satisfaction surveys between 2010 and 2015. Using the findings from these studies, it's fair to assume that out of the entirety of bus-users in London, those riding busses in the most affluent neighborhoods are more likely to be riding more satisfying and assumedly better kept busses.

In an attempt to categorize exclusion from transit, researchers Church, Frost, and Sullivan have created seven aspects of exclusion, the “physical, geographical, distance, economic, time-based, fear-based, and spatial, all of which can be seen to have a mobility component” (Shergold 2012, 412). That mobility component makes it difficult for the elderly and differently abled people to comfortably utilize all forms of shared transit, but they also will not benefit towards the push for active travel.

MODES OF TRANSPORTATION DISPLAYED IN BRITISH MEDIA

The Britishness of London’s public transit has been long-displayed in the media and thus holds the stake of global representation. The television show that has won six Emmys (Television Academy 2019), Fleabag, started off as a one-woman show in London (McIntosh 2019). Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s television series has received massive success globally since first airing on BBC in 2016. Despite the inherent Englishness of this series, Amazon opted to co-produce the original UK version instead of remaking the series for a US audience. Amazon’s choice to air the UK version instead of remaking the series, as has been done for the popular UK shows such as The Office and Shameless, signifies a new media connection between England and the United States (Waller-Bridge 2019).

This connection between BBC and Amazon, which extends to Waller-Bridge’s series Killing Eve as well, proves hopeful for Britain’s long-term goal of expanding its national cinema reputation. The desire for national identity in Britain to be emphasized through its cinematic output is summarized in former Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne’s, 2015 tax credit of 25% for television productions that qualify under the government scheme as British. In Osborne’s words, “a key part of [Britain’s] long term economic plan is supporting [the] creative industries that contribute billions to the economy and provide millions of jobs.” Waller-Bridge clearly understands the cultural and economic implications of her deal with Amazon, as she thanks Amazon for “coproducing Fleabag instead of remaking it” in her LA BAFTA Acceptance Speech, crediting this decision as a “real mark of change in the industry, and a bridge between the UK and American work” (Waller-Bridge 2019).

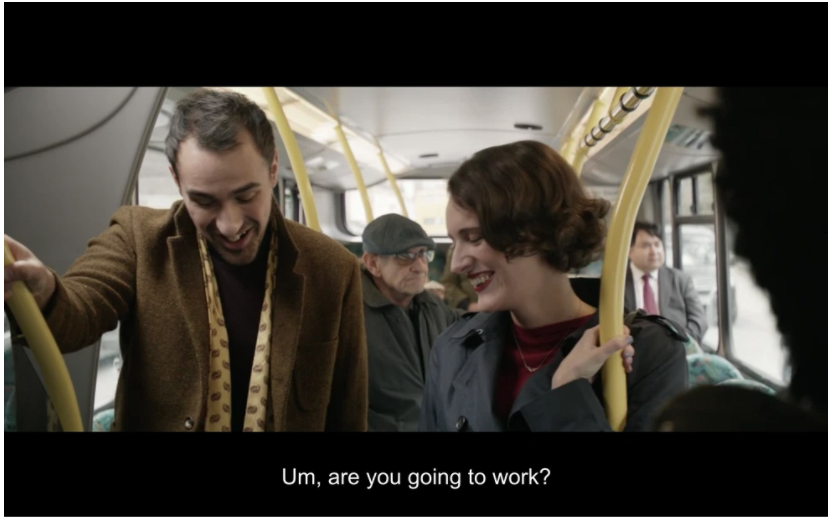

What’s important to the shared space of transit in this global representation of Britishness through Fleabag is the constant display of different modes of transportation throughout the series. An important display of shared transit is conveyed in the series’ first post-theme scene, in which Fleabag, the titular character, is shown reading a newspaper on a bus as she makes her way to a meeting about getting a loan for her small-business in London, England. On the bus, she meets Jamie Demetriou’s character, Bus Rodent, who has stereotypically “bad” teeth (Barlett 2013) and specifically English fashion, which is emphasized by Fleabag’s fashion and the newspaper which she reads. Of course, the bus itself also holds cultural weight as a meeting point for these two characters who later become romantically tied and sexually intimate, thus defining the bus as a pre-private place through this representation.

Fleabag’s indirect discussion of public transportation, which spans throughout the entire series through plot points about bicycles, cabs, and scenes such as this one on the bus, carry implications of shared transportation in London. Through the context of this bus scene occurring right before Fleabag has a bank meeting about a loan, in which she doesn’t get approved, this scene works to mark Fleabag as a member of the working class of London. Additionally, when they first speak, Bus Rodent asks Fleabag if she’s “going to work,” implying a further relationship between bus-riders and the working class and re-creating the subcultural group of workers who take busses in this media representation.

This representation within a series that has been widely critically acclaimed and was written by a native Londoner acts to prove that shared transit carries a pre-private weight to it in addition to connotations about subculture. The pre-private space of busses is implicitly compared to that of taxis later within the pilot episode. Where busses are pre-private meeting places, taxis act as a more sacred and internal space throughout the episode. First, Fleabag chooses to help a drunk girl on the side of the road get home safely in a taxi. Moments prior to putting the unnamed drunk girl safely in the cab, the character sees Fleabag for who she is, accurately calling her “sad face.” However, when Fleabag tries to seek further intimacy with the drunk girl, offering her to sleep at her place that night, the girl becomes offended and rejects the offer, getting into the taxi by herself. While the side of the road, an entirely public place where active travel would occur, lends itself to heavily pre-private encounters, the taxi itself rejects such occurrences and is reserved only for the drunk girl and the driver. This may suggest, then, that active travel better carries a pre-private atmosphere than taxis or cars, which exist nearly singularly in the private realm.

To further the privateness of taxis with the representation of Fleabag, late in the episode the audience follows Fleabag into the taxi her father orders for her in the middle of the night. In this taxi, we are introduced to a confession that is deeply connected to transit and sets the stage for season one. It is within this taxi that we discover the commonly argued cause of Flebag’s underlying sadness: the loss of her best friend and co-worker, Boo, to a darkly comedic cycling accident. Boo, as a pedestrian, was run over by a cyclist in the public space of the street. The confession of this intimate secret in a taxi furthers the argument that taxis and cars exist in a private realm instead of pre-private.

Another example of British media that often discusses modes of transportation on a global scale is that of The Smiths’ discography. As a band that has “inspired deeper devotion than any British group since the Beatles” (Ian Young 2013), The Smiths have earned their role in the global discussion of England’s mass transit. They regularly rely on allusions to different methods of transportation in their discography’s lyricism. In fact, about 26% of their songs make notable mention of some form of transportation, most commonly cars or general reference to the “streets,” followed by trains, bicycles, walking, busses, and finally general travel.

Both Fleabag and The Smiths therefore display the cultural importance of different modes of travel. It would be inarguably irresponsible to push for and create policy to prefer active travel over shared transit without considering the cultural weight of such pushes and policies.

Fleabag and Bus Rodent on the bus in the first post-theme scene of the series (Waller-Bridge 2016).

Fleabag and Bus Rodent on the bus in the first post-theme scene of the series (Waller-Bridge 2016).

About 26% of songs by the globally popular British band, The Smiths, reference different modes of transportation (Nathanson 2020).

About 26% of songs by the globally popular British band, The Smiths, reference different modes of transportation (Nathanson 2020).

Cyclescheme is an example of a push towards active travel (Cyclescheme 2015).

Cyclescheme is an example of a push towards active travel (Cyclescheme 2015).

Dogs are one of the most likely causes for a social interaction to occur on public transit. This dog went on many transit trips while his owners explored London (AnotherHeader 2015).

Dogs are one of the most likely causes for a social interaction to occur on public transit. This dog went on many transit trips while his owners explored London (AnotherHeader 2015).

CONCLUSION

While the streets in which walking and cycling occur in London are public spaces that allow for cultural encounters, they are inherently not the same as the hard-to-define pre-private and confined public spaces of London’s shared transit, in which culture is constantly reproduced and represented. The desire for better health and a better environment, such as the push for active travel represented in the Cyclescheme video included, is understandable and important, yet when pursued at the cost of the vital sociocultural occurrences in the temporal space of transit, much may be lost.

The established causes that lead one to break the civil inattention rule (dogs, children, small disruptions, etc.) are, in many ways, less likely to occur in a non-confined space. When people are constantly moving at their own pace, strangers within range of each cyclist or pedestrian’s senses change rapidly and, in general, are more scarce than when in the confined space of mass transit. A cyclist may be less likely to break the civil inattention rule for a few reasons. First, there may simply be less causes in their individual space to encourage them to break it. Likewise, for them to break the inattention rule they may have to place a more extreme version of special attention to the strangers in their range. Instead of starting conversation with the person next to them, a cyclist may have to pull over, stop biking, and catch their breath before starting the conversation. A pedestrian may have to approach a stranger from afar. This makes it harder to break the cultural norm of inattention. Additionally, the close observance of strangers is less likely for those opting for cycling since it is a less conversation and more individual action than riding transit or co-workers, peers, or friends.

Since the civil inattention rule is less likely to be broken during active travel, subcultures within London are less likely to interact through this mode of travel. Since it’s less social and arguably not a pre-private realm given the little potential for private encounters to be formed or private relationships or identities to be performed, the space of active travel does not allow for the same cultural creations as shared transit. While active travel is being pushed for due to many benefits in regards both public health and environmental wellbeing, two very important and noble causes, one must also consider the effects said push leaves on London’s culture.

References

Amazon. “London Busses Shirts.” Amazon. Accessed 2020. https://www.amazon.com/s?k=london+busses+shirt&ref=nb_sb_noss.

AnotherHeader. 2015. Photograph. London. https://anotherheader.wordpress.com/2015/01/01/england-london-dogs-on-the-tube/

Audiopedia. “What Is CIVIL INATTENTION? What Does CIVIL INATTENTION Mean? CIVIL INATTENTION Meaning & Explanation.” YouTube. YouTube, May 5, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AMZfTuWOiyM.

Bartlett, James. 2013. “The Tooth of the Matter: What's With the Stereotypes About British Dental Care?” BBC America. https://www.bbcamerica.com/anglophenia/2013/09/british-dental-care-the-tooth-of-the-matter.

Beanland, Christopher. 2013. "IS A CASHLESS SOCIETY REALLY ON THE CARDS?" The Independent, Jul 18, 42.

Busca, Nick. 2016. “Is Cycling to Work Really Cheaper than Public Transport?” BBC Worklife. BBC, December 7. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20161206-is-cycling-to-work-really-cheaper-than-public-transport.

Church, A., M. Frost, K. Sullivan. 2000. “Transport and social exclusion in London.” Transport Policy. July, 7, 3: 195-205.

Court, Carl. 2018. Photograph. London

Cyclescheme Ltd. 2015 “What Is Cyclescheme?” Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/131630071.

“Fleabag.” Television Academy. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.emmys.com/shows/fleabag.

Frasham, Mark, Danny Dorling , and Halford Mackinder. 2018.“Homelessness and Public Health.” BMJ, January 19.

Goodman, Anna. “Walking, Cycling and Driving to Work in the English and Welsh 2011 Census: Trends, Socio-Economic Patterning and Relevance to Travel Behaviour in General.” PLoS ONE 8, no. 8 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071790.

Goffman, Erving. Behavior in Public Places. NYC, NY: The Free Press, 1963.

Grisé, Emily, and Ahmed El-Geneidy. 2017“Evaluating the Relationship between Socially

(Dis)Advantaged Neighbourhoods and Customer Satisfaction of Bus Service in London, U.K.” Journal of Transport Ecology January, 58.

Heaney, Jim. 2020. “The Roots, and Consequences, of WNY's Racism.” Investigative Post, July 20. https://www.investigativepost.org/2020/07/20/the-roots-and-consequences-of-wnys-racism/.

Hill, Kate. 2019. “London Underground History.” Greater London Properties, April 30. https://www.greaterlondonproperties.co.uk/london-underground-history/.

Hoscik, Martin. 2015. “TfL Celebrates London's Diversity as Rainbow Bus Takes to the Streets.” MayorWatch, March 2. https://www.mayorwatch.co.uk/tfl-celebrates-londons-diversity-as-rainbow-bus-takes-to-the-streets/.

“In the Loop .” 2013. The Economist . October 5, 409 edition, sec. 8856.

Khan, Sadiq. 2019. “London Mayor Sadiq Khan: Time to Let Go of Segregation - Globally.” chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune, May 11. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-sadiq-khan-mayor-london-integration-perspec-0915-md-20160914-story.html.

Lee, Anru. 2007 “Subways as a Space of Cultural Intimacy: The Mass Rapid Transit System in

Taipei, Taiwan.” The China Journal, July, 58: 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/tcj.58.20066306.

McArthur, Jenny, Enora Robin, and Emilia Smeds. 2019.“Socio-Spatial and Temporal Dimensions of Transport Equity for London's Night Time Economy.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 121: 433–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.01.024.

McIntosh, Steven. 2019. “Fleabag: Six Things to Know about the Original Play.” BBC News. BBC, August 29. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-49482752.

McMillen, Stuart. 2009. “Bicycle Versus Bus.” Recombinant Records. http://www.recombinantrecords.net/docs/2009-01-Bicycle-versus-Bus.html

Peterson, Melike. 2016 “Living with Difference in Hyper-Diverse Areas: How Important Are Encounters in Semi-Public Spaces?” Social & cultural geography, July 20, 18, no. 8: 1067–1085.

Saloman, I, and M Ben-Avika. 1983. “The Use of the Life-Style Concept in Travel Demand Models.” Sage Journals.

Selwyn, Jeremy. 2018. Photograph. London.

Shergold, Ian, Graham Parkhurst. 2012. “Transport-related social exclusion amongst older people in rural Southwest England and Wales.” Journal of Rural Studies. October, 28, no.4: 412-421.

Soenen, Ruth. 2006. “An Anthropological Account of Ephemeral Relationships on Public Transport. A Contribution to the Reflection on Diversity.” ResearchGate.

Sohn, Heiwon. 2016. Chart. BBC Capital.

Taylor, Jack. 2016. Photograph. London.

The Smiths. 1984. “Hatful of Hollow.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 1984. “The Smiths.” Warner Music UK Ltd,.

The Smiths. 1985. “Meat is Murder.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 1986. “The Queen Is Dead.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 1987 “Louder Than Bombs.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 1987. “Strangeways, Here We Come.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 1987. “The World Won’t Listen.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 2008. “The Sound of the Smiths.” Warner Music UK Ltd.

The Smiths. 2011. “Complete.” Rhino UK.

Transport for London. “Tube.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://tfl.gov.uk/maps/track/tube.

“Using Buses in London.” 2020. Transport for London. https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/buses/using-buses-in-london.

Visit Britain . “Tube Etiquette: Top 9 Tips for Travelling on the London Underground.” Visit Britain, March 27, 2020. https://www.visitbritain.com/us/en/tube-etiquette-top-9-tips-travelling-london-underground.

Visit London. 2020. “London Buses.” visitlondon.com. Visit London, July 22. https://www.visitlondon.com/traveller-information/getting-around-london/london-bus?ref=more-ideas.

Visit London. 2020.“Oyster FAQs: How to Use Your Card.” visitlondon.com. Visit London, August 12. https://www.visitlondon.com/traveller-information/getting-around-london/oyster-faqs/how-to-use-your-card?ref=more-ideas.

Waller-Bridge, Phoebe. 2016. Fleabag, Season 1, Episode 1 [Video file].

Waller-Bridge, Phoebe. 2019. “Phoebe Waller-Bridge's Acceptance Speech | 2019 British Academy Britannia Awards,” October 26. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0znqOUfdeq4.

Wills, Ella. 2018. “London's Cycling Chief Claims London Cyclists Are Too White, Male and Middle Class... but Campaigners Say the Issue Is Infrastructure Not Diversity.” London Evening Standard | Evening Standard. Evening Standard. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/transport/campaigners-call-for-more-infrastructure-after-capital-s-cycling-chief-claims-london-cyclists-are-too-white-male-and-middle-class-a3850256.html.

Wozniak, Mark. “Buffalo Still Tops Poor Cities List.” WBFO. https://news.wbfo.org/post/buffalo-still-tops-poor-cities-list.