The Birth of Hallyu

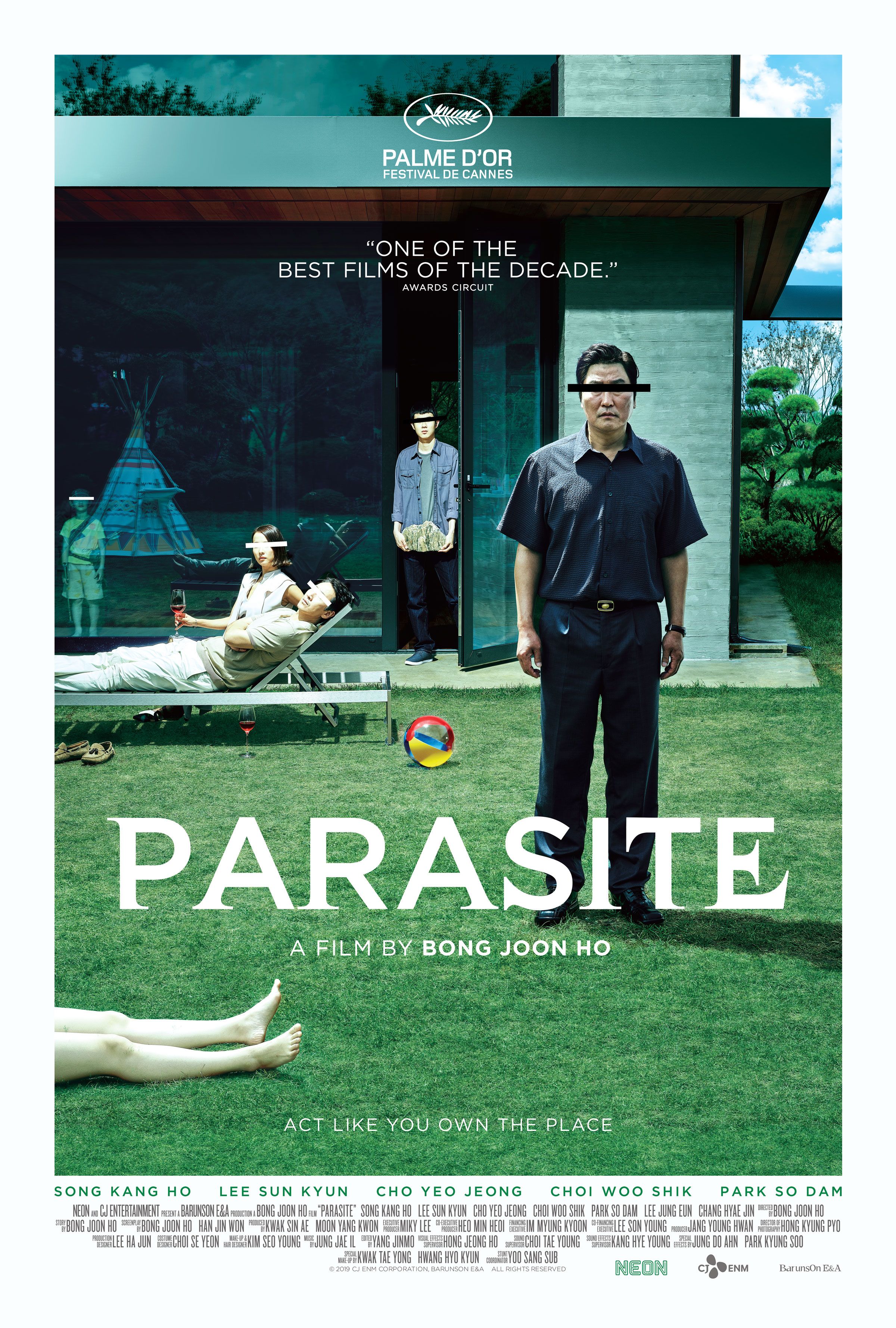

How the Korean government achieved immense soft power after years of cultural suppression.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, the world has watched and become engrossed in Korean culture and media. Affectionately called Hallyu (한류)—which translates to ‘Korean wave’— KPOP fandom culture has grown exponentially with the rise of worldwide social media, and it is hard for non-fans to escape the constant stream of Korean culture being delivered to the home pages of Twitter or Instagram. Korean drama is on the front page of Netflix and is being watched by millions of fans worldwide. Korean food and KBBQ has become popular and trendy, with more Korean restaurants popping up in cities than ever before. This love for Korean culture has elevated Korea to newfound popularity for tourists and has contributed to many economic gains. This late and sudden emergence of ‘Korean’ culture and power is not coincidental—rather, it is the consequence of a deliberate governmental fostering of culture after years of historical cultural suppression.

BTS, arguably the most popular KPOP band in the world. Bighit Entertainment.

BTS, arguably the most popular KPOP band in the world. Bighit Entertainment.

Korean BBQ which has been spreading throughout the West. LET'S MEAT KBBQ, Charlotte.

Korean BBQ which has been spreading throughout the West. LET'S MEAT KBBQ, Charlotte.

Emperor Sunjong of Korea, the last ruler before Japanese Occupation. Wikipedia.

Emperor Sunjong of Korea, the last ruler before Japanese Occupation. Wikipedia.

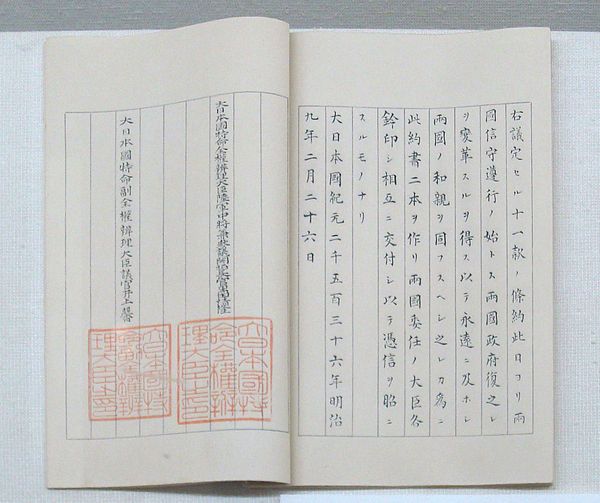

The Japan-Korea Treaty of 1876, the first on many unequal treaties signed by Korea. Japan Diplomatic Archives.

The Japan-Korea Treaty of 1876, the first on many unequal treaties signed by Korea. Japan Diplomatic Archives.

Preview to Annexation

Korea historically has had an isolationist policy, and had not opened itself up to Western trade. To the West, Korea was known as the “Hermit Kingdom1”. Its rulers had seen the Opium Wars in China, which only solidified their desires to stay an isolated kingdom2. During the mid-eighteenth century, Korea limited its outside trade to China and Japan. At the time, the Joseon Dynasty was a tributary state to Qing China. Western forces tried numerous times during the eighteenth century to establish trade, only to be turned away each time3. Japan, realizing the West’s efforts in opening up Korea, decided it wanted to open Korea first and exert more political influence. Korea was currently going through political turmoil as it changed leaders, and officials who were against the isolationist policy rose to power. Japan, taking advantage of this instability, plotted to give an extraordinary show of force in Korean coastal waters to pressure them to sign a Japan favored treaty between the two kingdoms4. This display of gunboat diplomacy worked, and this treaty served to open up Korea to Japan instead of the West5. This treaty was the starting point for many unequal treaties signed by Korea to come, and the preview to the eventual annexation of Korea into Japan.

1Jinwung Kim, A History of Korea: from 'Land of the Morning Calm' to States in Conflict (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012), pp 279.

2Ibid pp 281.

3Ibid pp 284.

4Key-Hiuk Kim, The Last Phase of the East Asian World Order: Korea, Japan and the Chinese Empire: 1860-1882 (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1980), pp. 205-231.

5Shinichi Kumamoto, “A Reckless Adventure in Taiwan amid Meiji Restoration Turmoil,” July 22, 2007.

Power Transfer to Japan

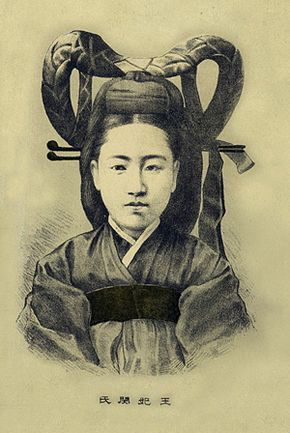

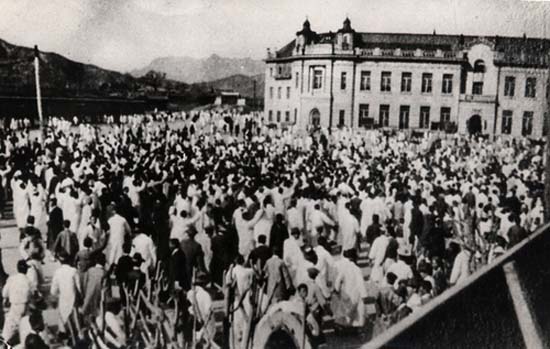

Unfortunately for Koreans, the Japanese had colonial expansion in mind with these unequal treaties. The Japanese win against China in the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895 ended Korea’s tributary relationship completely with China. A Japanese peace treaty signed with Russia in 1905 forced Russia to acknowledge Japan’s “paramount political, military, and economic interest” in Korea, and Russia seceded interest in influencing Korea. Eventually, through moves of subterfuge and military dominance—including the Japanese assassination of Korean Queen Min6—Japan was able to ensure military and economic dominance by 1904. In 1905, the signing of the Japan-Korea Treaty made sure that Korea would become a protectorate of Japan, and eventually it was annexed with the Emperor handing over his power to Japan7. In 1907, before the annexation, the emperor of Korea tried to secretly send three delegates to the Second Peace Conference without the knowledge of Japan. He wished for these delegates to bring to attention what was happening and hopefully inspire help. Unfortunately, the representatives were denied access to the meeting due to their status as a Protectorate of Japan8. Koreans did not take this peacefully, and riots ensued, but at this point it was far too late to change things, as other countries recognized Korea as under Japanese rule.

6박 종효, “‘일본인 폭도가 가슴을 세 번 짓밟고 일본도로 난자했다,’” shindonga.donga.com, November 9, 2004.

7“The Annexation of Korea,” The Japan Times, August 29, 2010.

8Carter J. Eckert et al., Korea, Old and New a History (Sǒul: Ilchokak, 1990), pp 245

Portrait of Queen Myeongseong, also known as Queen Min, who was assassinated by the Japanese. Wikipedia.

Portrait of Queen Myeongseong, also known as Queen Min, who was assassinated by the Japanese. Wikipedia.

Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty, signed in 1910, beginning the period of full Japanese rule in Korea. Yi Tae-jin.

Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty, signed in 1910, beginning the period of full Japanese rule in Korea. Yi Tae-jin.

Anti-Japan Righteous Armies who rebelled against Japanese authority with volunteer fighters. Frederick A. Mackenzie.

Anti-Japan Righteous Armies who rebelled against Japanese authority with volunteer fighters. Frederick A. Mackenzie.

Taken during the March 1st Demonstrations in 1919. This public display of resistance against Japanese authority led to many casualties of Korea protestors and the arrests of many activists. Historycollection.com.

Taken during the March 1st Demonstrations in 1919. This public display of resistance against Japanese authority led to many casualties of Korea protestors and the arrests of many activists. Historycollection.com.

Japanese Occupation

The Japanese occupation aimed to utterly squash Korean resistance in order to ensure the success and hegemony of the Japanese people9. The Japanese confiscated much of Korean farmland, forcing many Koreans to become tenant farmers10. Japanese officials forced Koreans into compulsory labor and taxed them heavily causing even more of them to lose their land. Rice production increased in Korea, but much of it was sent to Japan, reducing the amount of food for Koreans themselves11. In 1907, the Japanese passed a law that prohibited the publication of local newspapers. Through education, Japan aimed to impose its cultural ideals onto Korea while simultaneously marginalizing Korean history, culture, and people as ‘lesser beings’ or ‘backwards.’ Japan aimed to show the rest of the world that their modernization and civilization of Korea was legitimate due to the ‘backwards’ nature of Koreans12. This ideology only hammered home the idea to the West that Korean culture was ‘backwards’, leading to many of the negative conclusions the West had on Korea before hallyu.

9Jong-Wha Lee, “ECONOMIC GROWTH AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA, 1945-1992,” n.d..

10Shannon McCune, Korea's Heritage (Rutland, VT: Tuttle, 1966), pp. 86.

11“The Annexation of Korea,” The Japan Times.

12E. Taylor Atkins, Primitive Selves: Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910-1945 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010).

The Argument of "Justification"

The Japanese often justified this invasion by claiming they were ‘modernizing’ Korea, touting themselves as a modern country. However, many of these economic and infrastructural changes destroyed Korean culture and heritage sites. The Korean royal palace Gyeongbokgung was torn down in order to build the Japanese general government building13. When World War II neared, even teaching Korean and speaking Korean was prohibited14. Education was used as a way to assimilate Koreans in the Japanese empire and ‘modernize’ them. The Japanese used the idea of education producing a “loyal imperial citizen15” with correct political ideals and morals, and the school system was rarely equal between Japanese and Koreans16. While the Japanese modernization of Korea did improve its economic output, the atrocities committed will never make up for it.

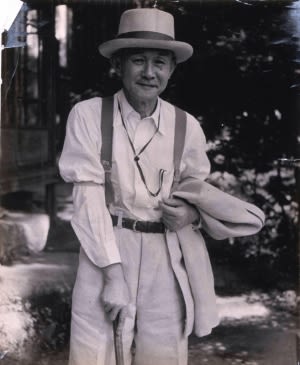

Yanagi Soetsu was one of the first foreigners to advocate for the importance of Korean culture and art. As Japanese critic of both art and imperialism, he first made a trip to Korea in 1916. He became enthralled with Korean art and history, and fought for cultural independence from Japan. He details in his works the importance of Korean ceramics and how art is the ‘soul’ of a nation17. Seen as a hero by many Koreans, and even awarded the Bogwan Order of Cultural Merit, he fought hard against Japan’s goal of removing and erasing Korean culture. His discourse Beauty of Sorrow influenced the global perception of Korea so much so that it continues to influence it today. Yanagi believed that art could be used to show the spirit of a nation, and that Korean art showed that it was “impossible” for Koreans to sustain national peace and happiness. He believed that Koreans live in constant pain and anguish, and that they would always be subservient to stronger powers18. While his advocacy of Korean culture and independence is important, he also served to further the global perception that Korea is helpless, and in that way, legitimized Japanese rule.

13Peter Bartholomew, “Choson Dynasty Royal Compounds: Windows to a Lost Culture,” Transactions: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch 68 (1993): pp. 11-44, pp. 30.

14“The Annexation of Korea,” The Japan Times.

15Mark Caprio, Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009).

16Ibid.

17Penny Bailey, “The Aestheticization of Korean Suffering in the Colonial Period: A Translation of Yanagi Sōetsu’s Chōsen No Bijutsu,” Monumenta Nipponica 73, no. 1 (2018): pp. 27-62, pp. 28.

18Ibid 38.

Some Japanese 'comfort women' POW. Japan claims these women volunteered, but in reality they were sex slaves abducted by Japan from Korea. These women were expected to have sex over fifty times per day. Medium.com.

Some Japanese 'comfort women' POW. Japan claims these women volunteered, but in reality they were sex slaves abducted by Japan from Korea. These women were expected to have sex over fifty times per day. Medium.com.

Gyeongbokgung palace, which has been restored to its former glory after the end of Japanese Occupation. Shutterstock.

Gyeongbokgung palace, which has been restored to its former glory after the end of Japanese Occupation. Shutterstock.

Yanagi Soetsu, hailed as a hero for his preservation of Korean art and culture during the Japanese Occupation. Textile Research Centre.

Yanagi Soetsu, hailed as a hero for his preservation of Korean art and culture during the Japanese Occupation. Textile Research Centre.

Portrait of Syngman Rhee, taken in 1956. syngmanrhee.or.kr

Portrait of Syngman Rhee, taken in 1956. syngmanrhee.or.kr

North Korean refugees fleeing south to escape the violence of war. dw.com.

North Korean refugees fleeing south to escape the violence of war. dw.com.

Performance of Arirang by Korea star So Hyang. Arirang has 3,600 variations and 60 different versions of the song, and is estimated to be around 600 years old. Youtube.

Leadup and Korean War

The fall of Japan in World War Two left Korea divided into two different zones, divided at the 38th parallel. The Soviet Union occupied the North while the US occupied the South. During this time, Korean culture was neglected and an afterthought for the US—rather, the US wanted to instill a positive image of themselves onto Koreans19. Many South Koreans, eager to be independent, were infuriated when the US declared a five year trusteeship before granting independence20. This anger was stoked by the fact that the US placed many Japanese-sympathizing Koreans into power. The US, realizing that this was not going well, declared they would have a general election to create an independent Korea. This election yielded Syngman Rhee, one of the first of many authoritarian rulers of modern day Korea. The election is widely suspected to have been rigged due to his pro-American stance. The North then established a communist government, with Kim Il-Sung as its leader. A war was about to break out once more.

The Korean War began when the North invaded the South on June 25th, 1950. This war caused the suffering of the entire Korean population, and many families were displaced in the effort to flee South to escape conflict. The war destroyed most of the Korean industry for both the North and the South, and resulted in over three million casualties21. Many children were left in orphanages and families were stuck on opposite sides of the border, unable to communicate with each other. The war still had very deep ties to the Korean people today, with the Korean people only wishing for peace for the two countries. Many just want to see their families and do not wish for conflict. The song “Arirang” is a traditional Korean folk song, and is considered to be the national anthem of Korea. It is sang in both countries as a symbol of unity despite the physical divisions spawned by the Korean War22. While the war came to an armistice in 1953, it has never officially ended.

19Charles K. Armstrong, “The Cultural Cold War in Korea, 1945–1950,” The Journal of Asian Studies 62, no. 1 (2003): pp 71-99.

20James L. Stokesbury, A Short History of the Korean War (New York, NY: Quill, 1990) pp 25-26.

21“The Korean War - CCEA - GCSE History Revision - CCEA - BBC Bitesize,” BBC News (BBC), accessed November 18, 2020.

22“N. Korea's Arirang Wins UNESCO Intangible Heritage Status,” Yonhap News Agency, November 27, 2014.

Yearning for Peace

On June 30 of 1983, Korean news company KBS broadcast a special called Finding Dispersed Families where they reunited families that had been separated due to the Korean war thirty-three years prior. What was supposed to be a one off special ended up running daily for an extra four-hundred and three hours until it concluded on November 14th of the same year23. The special had 100,952 applicants who wanted to find their family members and 10,189 families were reunited on live television thanks to this special24. This event rose to international prominence and was broadcast around the world, with KBS even working with US news agencies to find Korean families dispersed in the US. This broadcast was accepted to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 201525.

It initially only intended to reunite a small number of people, but the surge of applications from Koreans expanded it so that 50,000 people and their stories were aired on the show26. It became a national sensation and almost every household in the country had watched it, enthralled and living vicariously through those finding their family. This program also aimed to show the world the suffering that Koreans went through due to these wars, and served as an important cultural and historical moment in postwar reunification. The program was used as a bargaining chip with North Korea in an attempt to reunite families torn apart by the border27. This media is integral in showing the effects that war and occupation had on the general Korean public, as well as the yearning the Korean people have for peace and reunification with family members.

23Cultural Heritage Administration, "The Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast 'Finding Dispersed Families'". Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register, 2014.

24Steve Lohr, “War-Scattered Korean Kin Find Their Kin at Last,” The New York Times, August 18, 1983.

25The Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast ‘Finding Dispersed Families,’” Memory of the World (UNESCO, 2015).

26Lohr, “War-Scattered Korean Kin Find Their Kin at Last”.

27“The Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast ‘Finding Dispersed Families’”.

General overview of the program Finding Dispersed Families. Youtube.

One of the most famous reunifications between brothers. Don't forget to turn on English subtitles! Youtube.

A compilation of daughters finding their mothers, who were often forced to leave their children behind. Don't forget to turn on English subtitles! Youtube.

Two sisters being reunited after escaping bombings during the war. Don't forget to turn on English subtitles! Youtube.

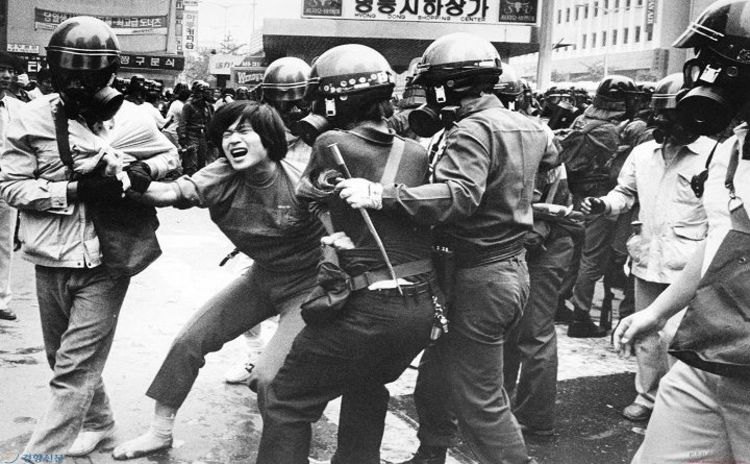

Police arresting a protestor during the April Revolutions. histhrill.com.

Police arresting a protestor during the April Revolutions. histhrill.com.

A mob of protestors during the April Revolution, with an estimated 30,000 people participating. Histhrill.com.

A mob of protestors during the April Revolution, with an estimated 30,000 people participating. Histhrill.com.

First of many Dictators

The countless authoritarian leaders South Korea withstood until 1987 boosted the economy but censored culture. The first ruler, Syngman Rhee, pushed through amendments that erased term limits, censored the press, and insured his control over the government28. During this time, support for his government was low. The April Revolutions broke out in 1960 due to the killing of a high schooler protesting government corruption. Rhee attempted to suppress these revolts, killing 186 people who protested against his regime29. Protests got so out of control that Rhee submitted his resignation later that year and fled the country. For a brief interim, the country had a democratic leader, who was elected with a cabinet. This government was much more left, but neglected the economic side of Korea30. The value of money quickly fell, and the government became unstable, and a coup occurred and was successful only one year later.

28Sŭng-hŭm Kil and Chung-in Moon, Understanding Korean Politics: an Introduction (Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press, 2001), pp. 143.

29“Remembering the April 19 Revolution,” www.donga.com, April 17, 2010.

30Andrew C. Nahm, Korea: Tradition Et Transformation ; a History to Korean People, 2nd ed. (Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym, 1996), pp. 412.

Park Chung-Hee's Modernisation

After successfully overthrowing the government, Park Chung-hee ruled from 1961 to 1979. While he reinstalled a presidential system in 1963, Park still tried to change things to work in his favor, forcing an amendment through that would allow him to run for a third term31. Park’s regime oversaw huge economic growth and industrialization. The first half of his regime is most noted for the economic growth and subsequent modernization of Korea. He re-established relations with Japan and kept close ties with the United States. He had an obsession with modernizing Korea, viewing Korean tradition and culture similarly to the Japanese. This emphasis on economic growth, left culture lagging behind. In fact, he tried his best to destroy old religious and cultural heritage in his quest of westernizing Korea and leaving the old behind.

The Saemaeul Undong Movement—translated to the New Community Movement—aimed to increase the quality of living for villages and help them industrialize32. The movement was launched by Park, and while it increased the standard of living and infrastructure in small towns, it also wished to change the rural population in ‘spirit’ by suppressing local superstition, worship, and culture33. This coincided with the peak of the Misin Tapa Undong movement, a movement stoked by the Japanese during the occupation in order to undermine local religion and label shamans and their rituals as backwards and wasteful34. The Saemaeul Undong Movement joined with the Misin Tapa Undong Movement with police and government approval in order to suppress local cults. They destroyed village shrines, sacred trees, totem poles, and arrested shamans35. This destruction of indigenous tradition and culture is thought to be a big reason as to why many Koreans adopted the Western Christian religion36.

31Nahm, Korea: Tradition Et Transformation pp 424.

32Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw, eds., “The Agricultural Crisis of the Late 1980s,” SOUTH KOREA - A Country Study, accessed November 19, 2020,

33Laurel Kendall, Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2010), pp. 10.

34Ibid pp 9.

35Ibid pp 10.

36Ibid.

Portrait of Park Chung-hee, Korea's second dictator. Britannica.

Portrait of Park Chung-hee, Korea's second dictator. Britannica.

Village totem-poles, the likes of which were targetted for destruction during the Saemmaeul Undong Movement. Homer Hulbert.

Village totem-poles, the likes of which were targetted for destruction during the Saemmaeul Undong Movement. Homer Hulbert.

Kim Jae-gyu, who assassinated Park. He was the director of the Korean Central Intellegence Agency and part of Park's regime. The assassination reason is still speculated. Wikipedia.

Kim Jae-gyu, who assassinated Park. He was the director of the Korean Central Intellegence Agency and part of Park's regime. The assassination reason is still speculated. Wikipedia.

Korea's final dictator Chun Doo-hwan. Globalsecurity.org.

Korea's final dictator Chun Doo-hwan. Globalsecurity.org.

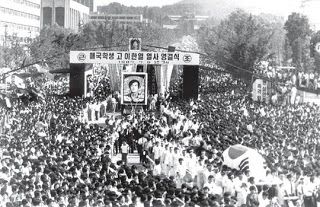

Lee Han Yeol, the symbol of opposition during the June Democracy movement. The student was wounded when he was hit in the head by a tear gas grenade, and died on July 5th. Korea Bridge.

Lee Han Yeol, the symbol of opposition during the June Democracy movement. The student was wounded when he was hit in the head by a tear gas grenade, and died on July 5th. Korea Bridge.

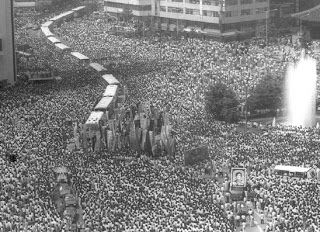

Lee han Yeol's fineral, where more than one million people attended. Koreabridge.

Lee han Yeol's fineral, where more than one million people attended. Koreabridge.

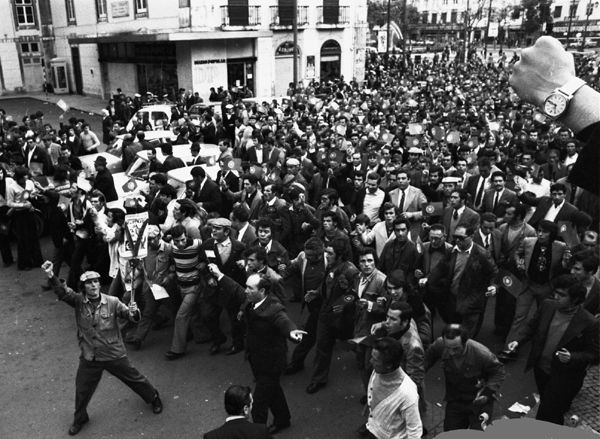

Crowds of protestors calling for free and fair elections during the June Democracy Movement. Koreabridge.

Crowds of protestors calling for free and fair elections during the June Democracy Movement. Koreabridge.

Voices for Democracy

In 1972, Park held a self-coup against his own government. Desiring more power and feeling threatened by the growing power of the opposition, he dissolved the national assembly and suspended the constitution37. During this time, he cracked down on free speech and censored the media even harder. He eventually created a new constitution that formally gave Park almost all power in government38. Despite his promises for a full democracy, he continued his dictatorship which induced growing civil unrest and opposition. He attempted to forcefully end these demonstrations, but his eventual murder of eight protestors under the guise of anti-communism caused significant bad press even through censorship, and only increased the protests for democracy, with people from all walks of life joining in. Eventually in 1979, Park was assassinated, finally ending his eighteen year rule39.

This did not end the dictatorship, however, as Major General Chun Doo-hwan executed yet another coup to take over the country only six days after the assassination. Protests continued against authoritarian rule, and new president Chun’s regime committed the Gwangju massacre, which ended up causing 1100 casualties40. Despite public dissonance, the economy under Chun continued to grow, and diplomatic relations continued to improve. Promises for democratisation were never acted on, and the eventual death of a protester under police interrogation spawned mass protests. Chun, not wishing to give into the pressure for a free and fair election, rejected the demands of protestors. This led into the June Democracy Movement in June of 1987, where more than one million people participated in a mass protest41. Due to the hosting of the 1988 Summer Olympic games, Chun did not want to resort to violence as all eyes were on Korea. His successor, Roh Tae-woo, gave in to demands and the election, for the first time in many years, was free and fair. Roh did win the presidency, and his government aimed to eliminate authoritarian rule. Finally, the era of dictatorship in Korea was over.

37Pankaj Mohan and Gil-sang Lee, Korea through the Ages, vol. 2 (Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do: Center for Information on Korean Culture, The Academy of Korean Studies, 2005), pp. 201-203.

38Byung-Kook Kim and Ezra F. Vogel, The Park Chung Hee Era: the Transformation of South Korea (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), pp. 27.

39Pankaj Mohan and Gil-sang Lee, Korea through the Ages, pp. 201-203.

40Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw, eds., “The Kwangju Uprising,” SOUTH KOREA - A Country Study, accessed November 19, 2020.

41“6월 민주항쟁,” Doopedia, accessed November 19, 2020.

Prelude to Hallyu

During these dictatorships, Korea focused heavily on its economy and industrialization. The rise of companies like Hyundai and Samsung were Korea’s golden children, with little attention paid to the arts. In fact, dictators actively subjugated the music industry and radio, censoring what music could and could not be played40. TV shows, music, and movies were all under tight control by dictators, and were often propaganda machines for the regime’s interests. The dissolution of the dictatorship and its censorship exposed Koreans to many more kinds of music and TV, as well as the resurgence of Korean rock, which was heavily inspired by the West. The introduction of foreign music via radio became a hit with the younger generation, and began to merge with traditional music. These new styles of music fused with Korean culture to form the beginnings of Hallyu. With the addition of outside influences and a lack of censorship, these new cultural developments thrived like never before.

40Aja Romano, “How K-Pop Became a Global Phenomenon,” Vox (Vox, February 16, 2018).

A selection of Korean trot music, the popular form of Korean music during Korean dictatorship. Youtube.

Samsung TV ads from the 70s to 80s. By this time, TVs were becoming more and more common in korean households, whereas they were a luxury in the 60s.

This song is the definite beginning of KPOP, and the inspiration for many Korean bands in the 90s. By their disbandment in 1996, they had set into motion one of the largest music industries in the world. YouTube.

Considered to be the first idol group, H.O.T.—standing for Highfive of Teenagers—was a huge sensation. This song established their popularity in Korea. Youtube.

Beginnings of KPOP

The beginnings of KPOP started on April 11, 1992 with the boy band Seo Taiji and Boys and their performance of their single “Nan Arayo.” This was a fusion of both modern American-style pop music and South-Korean culture, and it was a smash hit with the Korean population, topping music charts for seventeen weeks43. Their experimentalism led to many more bands following through, breaking more boundaries which were priorly forbidden by the authoritarian style government. Eventually, studios took over this new music scene and began creating idol groups, with the first popular one being H.O.T. with his target audience being teenage fans. This whole time, KPOP was building itself up as a brand and preparing itself for national success.

43Romano, “How K-Pop Became a Global Phenomenon”.

Beginnings of KDRAMA

The beginnings of Korean drama began in the sixties, though they were used heavily as propaganda machines by the government. They began to boom in the 70s, but the government put heavy restrictions on them, viewing them as “poor taste”44. It was only in the 80s, with the assistance of Japanese influence, that dramas began focusing on the lives of the younger population and having love as a main theme, which is the most common in dramas today. The relaxation in the 90s of government censorship led to more investment of both money and effort into dramas. This era also marked the beginning of the export of dramas like Autumn in my Heart and Winter Sonata, to the surrounding countries, jumpstarting the Korean wave and an influx of incoming tourists from nearby Asia wanting to find love like in their favourite drama. Korean tourist sites even show where dramas like Winter Sonata were filmed for these tourists45.

44Kalbi, “K-Drama Series – A Brief History of K-Dramas,” Korean Culture Blog, October 10, 2016.

45“Korean TV Drama,” Winter Sonata: The Official Site For Korean Tourism (Korea Tourism Organization), accessed November 19, 2020.

Winter Sonata was one of the first dramas to break through outside of Korea. This drama was loved so much in Japan, especially by middle age women, most notably for the actor Bae Yong-jun, who was nicknamed Yon-sama by Korean fans. It is estimated that he brought in $2.3 billion in tourism and merch sales. Youtube.

Though not to the success of Winter Sonata, Autumn in my Heart is considered a pioneer of melodramatic dramas which were one of the main focuses of the Korean Wave. Youtube.

A statistic showing the currencies and their values during the Asian Financial Crisis. grips.ac.jp

A statistic showing the currencies and their values during the Asian Financial Crisis. grips.ac.jp

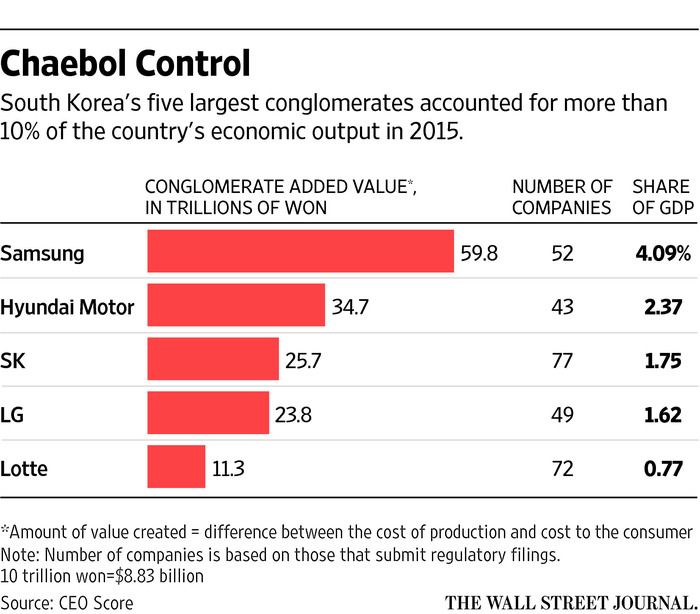

The economic impact of the five largest South Korean chaebols in 2015. Wall Street Journal.

The economic impact of the five largest South Korean chaebols in 2015. Wall Street Journal.

Facilitating Hallyu

Studies show that hallyu was not spontaneous, instead it was the result of economic policies that boosted cultural output46. This began with the ban on foriegn travel for Koreans in the early 1990s. This allowed its citizens to experience more of the Western world and its culture. This also allowed for more Koreans to study abroad or intern in foriegn companies before settling down in Korea. This newfound perspective of Western-travelled and educated Koreans introduced different business practices and new forms of music, art, and media into Korea47. This also created a new generation of ‘young’ Koreans with different perspectives from the traditional older generations. In 1996, Korea also lifted censorship laws that prohibited the entertainment sector from highlighting and showcasing controversial topics, such as politics and rebellion. This allowed for the younger generation to showcase their bolder, newer ideas without fear of censorship. These changes set the stage for the country.

One of the most important events that facilitated the spread of Hallyu was the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98. Despite Korea’s steady growing economy, Korea had a large amount of foreign debt, and the Korean currency—won—began falling in value48. Investors began to panic and many Korean companies went bankrupt, specifically Korean chaebols. Chaebols are large Korean industrial conglomerates that the country had come to rely on, and their large scale failure and bankruptcy during this crisis left the government realizing the country needed to diversify49. The Korean president Kim Dae-jung realized that Korea needed to fix its foriegn image, and so pushed for information technology and popular culture as the two concurrent avenues for Korea’s future. The government believed that popular culture and cutting edge technology could become a hugely profitable export product while simultaneously rebranding Korea’s shaky image50. Chaebols like Samsung began funding Korean movies and shows that would advertise their products while growing the entertainment industry51.

46Molly Mastantuono, “Hooray for Hallyu,” Bentley University Newsroom, October 14, 2020.

47“Korean Wave (Hallyu) - Rise of Korea's Cultural Economy & Pop Culture,” Martin Roll, August 2020.

48Ibid.

49Ibid.

50Ibid.

51Ibid.

The Power of Culture

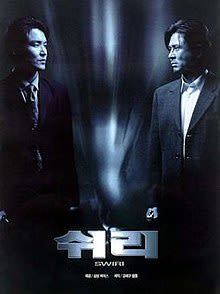

In 1998, the Korean Ministry of Culture, armed with a budget increase, began a large-scale five year plan to increase domestic industry. This is in part because Korea wished to compete globally and domestically with Japanese culture, which was popular on the Korean black market52. Previous to this year, Japanese cultural imports were banned in Korea, but the country was looking to lift these restrictions. The Ministry of Culture provided equipment and scholarships to colleges and universities, aiming to increase culture industry departments; by 2005, there were almost 300, growing from nearly zero53. It was during these formative years that hit movies such as Shiri (1999) and My Sassy Girl (2001) were released, leading to smash hits domestically and abroad, specifically in Southeast Asia. This, combined with the regional success of television hits like Autumn in my Heart (2000) and Winter Sonata (2002), were the main players in the beginning of the Korean Wave54. The government, clearly realizing the growing soft power and popularity of culture, opened the Korea Culture and Content Agency to encourage these exports. The entertainment industry had only received heavy government investment in the late 90s, and went from $8.5 billion in 1999 to $43.5 billion in 200355. The shift towards culture had begun, and Korea’s brand would irreversibly change.

52Norimitsu Onishi, "South Korea adds culture to its export power". The New York Times, 29 June 2005

53Ibid.

54“Korean Wave (Hallyu) - Rise of Korea's Cultural Economy & Pop Culture.”

55Onishi, "South Korea adds culture to its export power".

Shiri movie, the first hit film Korea had, and often noted as the 'start' of hallyu. Wikipedia.

Shiri movie, the first hit film Korea had, and often noted as the 'start' of hallyu. Wikipedia.

My Sassy Girl, which spawned foreign many remakes after its release. Wikipedia.

My Sassy Girl, which spawned foreign many remakes after its release. Wikipedia.

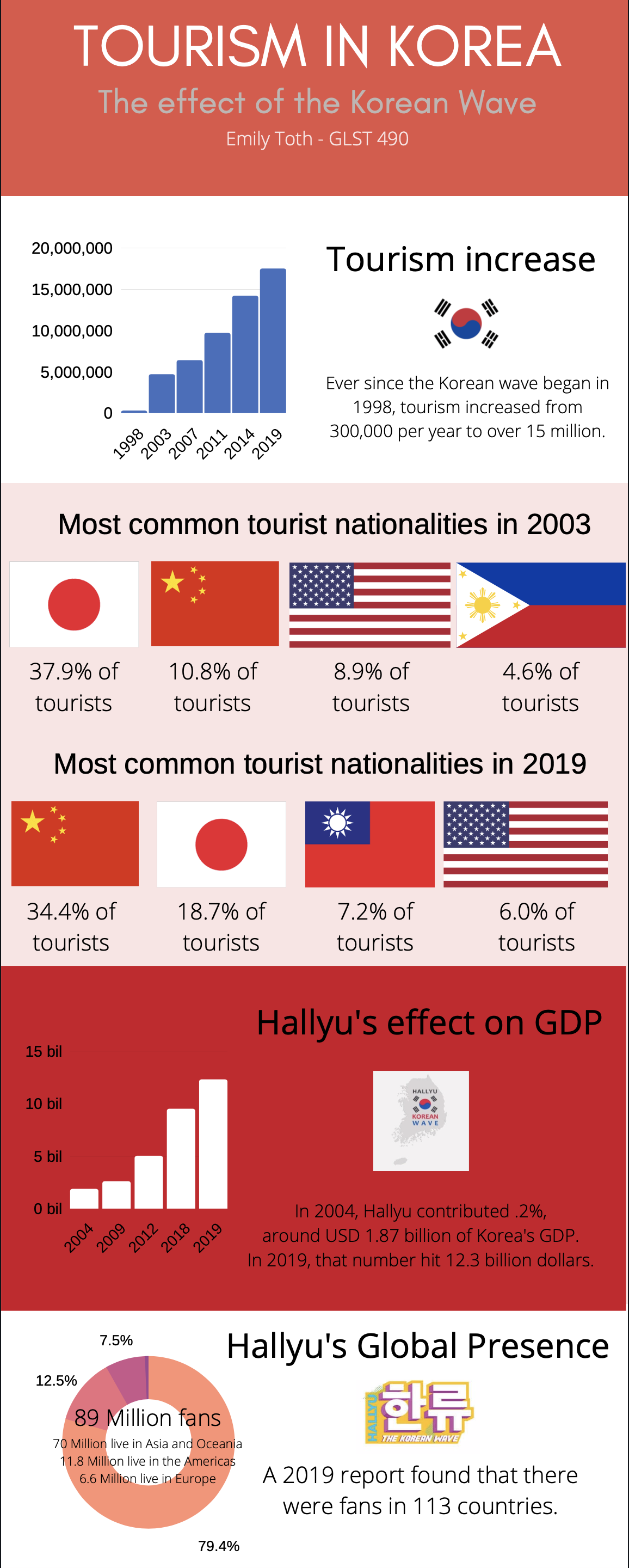

Infographic showing the rate of tourism in Korea due to Hallyu. Original Content.

Infographic showing the rate of tourism in Korea due to Hallyu. Original Content.

Conclusion

The entertainment industry and its growth in the late nineties lends much of its power to the introduction of a true democracy in Korea and the desire of the government to ‘rebrand’ the global image of the country. This effort has been immensely successful, with the brand of Korea completely changing from an authoritarian, war-torn country to a global cultural empire56. While the Korean Wave seems to have emerged from nowhere, in reality a number of factors, policies, and government efforts facilitated its spread across the globe, and the resulting impact leaving Korea with an unimaginable amount of soft-power. The story of Hallyu is a prime example of how a government can skillfully change the image of a country through the use of culture.

56Yi Zhou and Liz Rodwell, “The Korean Wave (Hallyu),” Society for East Asian Anthropology, July 30, 2014.

Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century.

Works Cited

“6월 민주항쟁.” Doopedia. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?docId=1166426.

“The Annexation of Korea.” The Japan Times, August 29, 2010. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2010/08/29/editorials/the-annexation-of-korea/ .

“The Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast ‘Finding Dispersed Families.’” Memory of the World. UNESCO, 2015. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/memory-of-the-world/register/full-list-of-registered-heritage/registered-heritage-page-8/the-archives-of-the-kbs-special-live-broadcast-finding-dispersed-families/.

Armstrong, Charles K. “The Cultural Cold War in Korea, 1945–1950.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62, no. 1 (2003): 71–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096136.

Atkins, E. Taylor. Primitive Selves: Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910-1945. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010.

Bailey, Penny. “The Aestheticization of Korean Suffering in the Colonial Period: A Translation of Yanagi Sōetsu’s Chōsen No Bijutsu.” Monumenta Nipponica 73, no. 1 (2018): 27–62. https://doi.org/10.1353/mni.2018.0001.

Bartholomew, Peter. “Choson Dynasty Royal Compounds: Windows to a Lost Culture.” Transactions: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch 68 (1993): 11–44.

Caprio, Mark. Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009.

Cultural Heritage Administration, "The Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast 'Finding Dispersed Families'". Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register, 2014.

Eckert, Carter J., Ki-baik Yi, Yŏng-ik Yu, Michael Robinson, and Wolfgang Eric Wagner. Korea, Old and New a History. Sǒul: Ilchokak, 1990.

Kalbi. “K-Drama Series – A Brief History of K-Dramas.” Korean Culture Blog, October 10, 2016. https://koreancultureblog.com/2016/10/10/k-drama-series-a-brief-history-of-k-dramas/.

Kendall, Laurel. Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2010.

Kil, Sŭng-hŭm, and Chung-in Moon. Understanding Korean Politics: an Introduction. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press, 2001.

Kim, Byung-Kook, and Ezra F. Vogel. The Park Chung Hee Era: the Transformation of South Korea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Kim, Jinwung. A History of Korea: from 'Land of the Morning Calm' to States in Conflict. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Kim, Key-Hiuk. The Last Phase of the East Asian World Order: Korea, Japan and the Chinese Empire: 1860-1882. Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1980.

“Korean TV Drama.” Winter Sonata: The Official Site For Korean Tourism. Korea Tourism Organization. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://english.visitkorea.or.kr/enu/CU/CU_EN_8_5_1_1.jsp.

“The Korean War - CCEA - GCSE History Revision - CCEA - BBC Bitesize.” BBC News. BBC. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zqqd6yc/revision/1.

“Korean Wave (Hallyu) - Rise of Korea's Cultural Economy & Pop Culture,” Martin Roll, August 2020, https://martinroll.com/resources/articles/asia/korean-wave-hallyu-the-rise-of-koreas-cultural-economy-pop-culture/.

Lee, Jong-Wha. “ECONOMIC GROWTH AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA, 1945-1992,” n.d. http://smesindia.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Korea.pdf.

Lohr, Steve. “War-Scattered Korean Kin Find Their Kin at Last.” The New York Times, August 18, 1983.

Mastantuono, Molly. “Hooray for Hallyu.” Bentley University Newsroom, October 14, 2020. https://www.bentley.edu/news/hooray-hallyu.

McCune, Shannon. Korea's Heritage. Rutland, VT: Tuttle, 1966.

Mohan, Pankaj, and Gil-sang Lee. Korea through the Ages. 2. Vol. 2. Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do: Center for Information on Korean Culture, The Academy of Korean Studies, 2005.

“N. Korea's Arirang Wins UNESCO Intangible Heritage Status.” Yonhap News Agency, November 27, 2014. http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/culturesports/2014/11/27/39/0701000000AEN20141127000300315F.html.

Nahm, Andrew C. Korea: Tradition Et Transformation ; a History to Korean People. 2nd ed. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym, 1996.

Onishi, Norimitsu, "South Korea adds culture to its export power". The New York Times, 29 June 2005

“Remembering the April 19 Revolution.” www.donga.com, April 17, 2010. http://www.donga.com/en/article/all/20100417/264838/1/Remembering-the-April-19-Revolution.

Romano, Aja. “How K-Pop Became a Global Phenomenon.” Vox. Vox, February 16, 2018. https://www.vox.com/culture/2018/2/16/16915672/what-is-kpop-history-explained.

Savada, Andrea Matles, and William Shaw, eds. “The Agricultural Crisis of the Late 1980s.” SOUTH KOREA - A Country Study. Accessed November 19, 2020. http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-12321.html.

Savada, Andrea Matles, and William Shaw, eds. “The Kwangju Uprising.” SOUTH KOREA - A Country Study. Accessed November 19, 2020. http://countrystudies.us/south-korea/21.htm.

Stokesbury, James L. A Short History of the Korean War. New York, NY: Quill, 1990.

Zhou, Yi, and Liz Rodwell. “The Korean Wave (Hallyu).” Society for East Asian Anthropology, July 30, 2014. http://seaa.americananthro.org/2014/07/the-korean-wave-hallyu/.

박 종효. “‘일본인 폭도가 가슴을 세 번 짓밟고 일본도로 난자했다.’” shindonga.donga.com, November 9, 2004. https://shindonga.donga.com/3/all/13/101476/1.