"Strajk Kobiet!"

The Women of Poland vs. The Constitutional Tribunal

My Story

Saturday afternoon trips to the Greenpoint markets, the smell of barszcz bialy (Polish White Borscht) brewing in the morning, and early Sunday masses are some key features of my childhood growing up Polish in New York City. My parents immigrated to the states in the early 1990s chasing the American dream, which resulted in my peculiar upbringing. I like to believe that I had the best of both worlds; unlimited access to bacon, egg, and cheese’s at the corner bodega and freshly made pierogi after school. This fusion of cultures contributed to my interests in language and travel, which is the reason why I applied for the Global Studies minor.

Figure 1: Old Poland Bakery in Greenpoint, New York.

Figure 1: Old Poland Bakery in Greenpoint, New York.

When brainstorming ideas for my capstone project, I couldn’t decide. There was just too much to talk about; beauty standards in Korea, the prison system in Finland, sustainability in China. Soon I realized that there were some serious issues closer to home that deserved attention; Women's Rights in Poland. As a child, I would regularly visit my friends and family back in Poland during the summer. As I’ve maintained these connections throughout the years, I noticed some prominent disparities between life in Poland and life in the United States, especially for women. When discussing services such as Planned Parenthood, my friends couldn’t comprehend that such a resource existed. Similarly, when sharing photos from the Pride Parade in June, they marveled at the peace and community at the event. They claimed that they would never consider going to such an outing because of the potential dangers associated with sexual expression in Poland. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, I was unable to visit Poland these past two summers, and experience these attitudes firsthand. However, after some research, I soon realized how little I knew about my own country of origin. As a result, in this capstone I will explore how women's reproductive rights are represented in the Polish Constitution, and what this means for the future of Polish democracy?

Figure 2: Family's place of origin; Krakow, Poland.

Figure 2: Family's place of origin; Krakow, Poland.

Poland's Pseudo-Democracy

Throughout the history of Poland, the church has been the defender of freedom and a source of protection from opposing forces. When the country fell into the hands of Stalin, post- World War II, the communist government experienced difficulty undermining the historical significance of the church given that nearly 100% of the population was Roman Catholic (Eberts, 1998). Initially, the communist government decided to coexist with the church by granting the institution freedoms to worship without interference, reconstruction of numerous buildings with state funding, and military assistance with Corpus Christi processions (Eberts, 1998). The church was even given the autonomy to publish Catholic periodicals: Tygodnik Powszechny (Universal Weekly) and Znak (The Sign) . The regime believed that this church-state partnership would positively influence Polish affinity for the new order.

Figure 3: Painting of Our Lady of Czestochowa. On the Virgin Mary's left cheek you can notice scratches as a result of communist confiscation that damaged the painting.

Figure 3: Painting of Our Lady of Czestochowa. On the Virgin Mary's left cheek you can notice scratches as a result of communist confiscation that damaged the painting.

However by the early 1950s, tensions began to grow between the two influences which ultimately led to a widespread censorship on church publications and suspension of church programs. The regime confiscated the church’s charitable organizations, hospitals, and artifacts (Eberts, 1998). This resulted in a wave of backlash from the public, and further strengthened Polish support of the Catholic church. At the time, the public attitude was: they can seize our monuments, and threaten our clergy, but they can never take away our faith. By April of 1950, the communists realized that they couldn’t win against the Catholic church, and abruptly signed an agreement that promised certain freedoms and benefits to the church, in exchange for the promotion of respect for the communist authorities (Eberts, 1998). Whenever the regime needed the church to mitigate internal affairs, it would grant concessions to the institution. This was especially prominent during the 1980s Solidarity Movement led by Lech Walesa.

Figure 4: Strike at the Gdansk Lenin shipyard in 1988.

Figure 4: Strike at the Gdansk Lenin shipyard in 1988.

By the 1980s, the Polish public was tired of the communist government’s attempts to destroy labor unions through the imposition of martial law. The Poles demanded the right to form trade unions, the right to peacefully protest, and the right to freely express their ideas in the media (Kubow, 2013). Despite the church-state agreement, the church continued to serve as a safe haven for persecuted members of the Solidarity Movement, who gathered in churches as a symbol of opposition to the communist authorities. This, once again, made the Catholic church a symbol of freedom, and firmly established the congregation as a legitimate authority in the country (Eberts, 1998). The Poles wanted their country back, and they did so with the Church at the forefront of the movement.

After the collapse of communism in the summer of 1989, the newly autonomous government had to reestablish itself, and so did the role of the Catholic Church in its political affairs. Prior to the collapse of the communist government, the 1989 Statute on the Relationship between the Catholic Church and State was passed, which guaranteed the church full control over its offices, and provided a variety of tax and customs exemptions (Eberts, 1998). Furthermore, two additional documents; the Concordat and the Constitution, established the basis for newfound church-state relations and laid the blueprint for Poland’s newfound democracy. The new Concordat was meant to replace the previously passed Statute, and was initially passed without the approval of the Polish Parliament. The purpose of this document was to set out the rights and responsibilities of the Catholic church from the perspective of the Holy See. Some provisions of the Concordat included; state subsidies for Catholic schools and educational institutions owned and operated by the church, textbooks used in religious courses were to be determined by the Catholic church without any consultation with the government, and canon law matrimonies would hold the same legal status as civil matrimonies (Ebert, 1998). Interestingly, the first article of the Concordat declared that “the State and Catholic Church are, each in its own domain, independent and autonomous,” but the word “separate” was not directly mentioned in the document, instead the document mentions how the church and state will “cooperate for the development of mankind and the common good”(Eberts, 1998). The proposed statute sparked intense debate given the unprecedented autonomy being granted to the church, yet on January 8th, 1998, with 273 votes in support and 161 votes in opposition, the Polish Sejm passed the 1993 Concordat.

Figure 5: The Polish Parliament building in Warsaw, Poland.

Figure 5: The Polish Parliament building in Warsaw, Poland.

By 1997, government officials began drafting the new Polish constitution, which was meant to lay out the foundations of democracy. The Catholic church played a prominent role in the drafting process under the pretext that despite being a legal document, the constitution should preserve the national traditions and Catholic values of the country (Eberts, 1998). The involved bishops demanded that there be a reference to God in the preamble, the Constitution should guarantee the protection of human life from conception until death, and that marriage can only be granted to members of the opposite sex (Eberts, 1998). Uniquely, the Polish Constitution incorporates many of the church’s demands without turning Poland into a denominational state. How was this accomplished? Through a simple play on words. For example, the preamble mentions God as the source of “truth, justice, goodness, and beauty,” but also mentions how non-believers can obtain these virtues through their respective entities (Eberts, 1998). Furthermore, the preamble refers to the Christian heritage of the Polish Nation, but never directly mentions Catholicism or the Church specifically (Eberts, 1998). As a result, the constitution was ratified on April 2nd, 1997 giving birth to Poland’s pseudo-democracy.

Figure 6: Celebrations from May 3rd, 1791, when Poland signed its first written constitution in Europe.

Figure 6: Celebrations from May 3rd, 1791, when Poland signed its first written constitution in Europe.

The Current Political Arena

As we make our way towards the current political climate in Poland, you can clearly see the the divide between the liberal and conservative forces in the country. In the 2020 presidential election, president-elect Andrzej Duda and Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski battled head-to-head for the presidential seat. Both men were born into upper-class families, and worked in academia prior to entering politics as ministers for the European Union (Pronczuk, 2020). Despite their similar upbringing, their political campaigns couldn’t have been more divergent. Duda, a member of the Law and Justice (PiS) party, ran on an anti-LGBTQ platform with slogans such as; “LGBT are not people, they are an ideology” (Fitxsimons, 2020). The politician's campaign gained traction through radical promises such as eliminating the "rainbow plague" and establishing "LGBT-free zones" attracting an older, conservative audience. The success of radical political campaigns has been demonstrated by former U.S. president Donald Trump who won the 2016 presidency by promising to “Make America Great Again,” and build a wall to eradicate illegal immigration into the states. Upon his visit to the White House, president Trump publicly endorsed Duda’s candidacy by stating, “He’s doing a terrific job. The people of Poland think the world of him” (Pronczuk, 2020).

Figure 7: President Trump endorses Andrzej Duda's presidential candidacy in 2020.

Figure 7: President Trump endorses Andrzej Duda's presidential candidacy in 2020.

Navigated by the conservative forces of Parliament and the Catholic church, Duda pledged to ban same-sex marriage and LGBTQ adoption rights in an attempt to reinstate the importance of “traditional families” (Fitzsimons, 2020). On the other hand, Trzaskowski entered the presidential election relatively late, but had ample time to catch up as a result of the election postponement. Trzaskowski identified as a pro-democracy activist, and an avid supporter of LGBTQ+ rights and the European Union (Scislowska, 2020). As mayor of Warsaw, he signed a declaration of tolerance for the LGBTQ+ community, which entailed social service programs for gay youth that had been rejected by their families, and even road on a float in the city’s annual pride parade (Scislowska, 2020). In regards to his political agenda, he wanted to prevent the EU from punishing Poland with financial sanctions for violating human rights policies. He encouraged that the EU to bypass the national government, and make its funding directly available to local governments given the growing chasm between the nationalists and progressives (Scislowska, 2020).

Figure 8: Rafal Trzaskowski, mayor of Warsaw, marches in 2019 PRIDE Parade.

Figure 8: Rafal Trzaskowski, mayor of Warsaw, marches in 2019 PRIDE Parade.

On July 13th, 2020, the National Electoral Commission announced that with 100% of the votes counted, Duda secured 51.03% of the vote while Trzaskowski gained 48.97% of the vote, announcing Andrzej Duda as the next president by a margin. This has been labeled as the closest presidential election since the end of communism in 1989 (Pronczuk, 2020). Despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the turnout was 68.18% with Poles living in Poland rushing to the polls, as well as those living abroad in the United States and the United Kingdom. One important question to consider is; Was it a fair fight? The PiS government used state media to promote its views and silence opposing ones, manipulated courts, and gained support through instilling fear and division (Pronczuk, 2020). There was no opportunity for a televised debate over fear of state broadcaster’s manipulating the footage to make the PiS candidate appear more favorable in the public eye (Pronczuk, 2020). How can the Polish public be expected to make an informed decision about their future political representatives, when their judgement is clouded by propaganda?

Figure 9: "Polands Conservative President Duda re-elected" -BBC News

Silenced No More

After the re-election of Andrzej Duda, and the majority of parliamentary seats filled by PiS representatives, the political party embarked on fulfilling it’s campaign promises; starting with abortion. Poland had strict abortion laws since the early 1990s, with abortion being legal under three conditions; if the pregnancy resulted from rape/incest, if the mother’s life was at risk, or if it was predetermined that the fetus was developing abnormally (Mortensen, 2021). However, in October of 2020 the constitutional tribunal revised the abortion clause by deeming abortions on the basis of fetal abnormalities unconstitutional (Mortensen, 2020). It was identified that legal personhood begins at conception, therefore, the unborn fetus deserves the same civil liberties and protections (Gliszczyńska- Grabias, 2020). Given that approximately 98% of abortions in Poland are conducted on the basis of fetal defects, this was a near-total ban on abortion in the country (Picheta, 2020). This resulted in public uproar, as hundreds of thousands of protestors, predominantly women between the ages of 18-35, hit the streets at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 10: "Mass Protests in Poland Against Law Banning Almost All Abortions" -BBC News

In 2016, previous attempts have been made to restrict abortion, however, massive public demonstrations resulted in the retraction of the legislation (Picheta, 2020). By passing this new abortion ban during the height of the pandemic, the government hoped to avoid large public protests. However, women found alternative methods to protest while simultaneously abiding COVID-19 precautions by using their vehicles to block the main roundabout to the Polish capital (Mackintosh, 2020). Protestors would honk their horns, shout slogans, hold black umbrellas ( a symbol of the abortion right’s movement), and attached “Women’s Strike” posters to their windows (Mackintosh, 2020). This infringement on women’s rights sparked the birth of numerous women’s organizations, particularly Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet (National Women’s Strike), which advocates for legal abortion per request, sex education in schools, and freely available contraceptives. Additionally, the organization heavily criticizes the bias of the Constitutional Tribunal, and the Supreme Court of Poland influenced by the PiS party (Forbes). In a country of 38 million inhabitants, fewer than 2,000 legal abortions are performed annually, but approximately 200,000 procedures are performed illegally or abroad ( The Guardian, 2020).

Figure 11: "Strajk Kobiet" banners in the streets of Warsaw after announcement of the abortion ban.

Figure 11: "Strajk Kobiet" banners in the streets of Warsaw after announcement of the abortion ban.

The Handcuffed Uterus

In an attempt to protect the personhood of the unborn fetus, the Constitutional Tribunal endangers the life of the living mother. This is demonstrated in the case of Izabela, a 30-year-old woman in her 22nd week of pregnancy, who abruptly died from septic shock during delivery (Reuters, 2021). She is the first woman to die as a result of the October 2020 ruling (Reuters, 2021). Izabela, who’s last name remains hidden for privacy reasons, carried until full term despite the scans showing numerous defects to the developing fetus. When the doctors realized that the unborn child wasn’t going to make it, they waited until the heartbeat stopped before treating Izabela, but by that time it was too late (Reuters, 2021). During transport to perform a cesarean section, Izabela’s heart stopped, and she died despite efforts to resuscitate. In 2012, a similar instance occurred in Ireland, when 31 year-old Savita Halappanavar died after she was refused an abortion despite serious complications to the pregnancy (Reuters, 2021). This served as the catalyst for the legalization of abortion laws in Ireland (Reuters, 2021).

Figure 12: Justice of Izabela !

Figure 12: Justice of Izabela !

When asked to comment on the tragedy, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki stated that the blame should not be placed on the abortion ban, but on the doctor’s malpractice. Under the constitution, abortion is legal under circumstances when the mother’s life is in danger. Then why didn’t the doctors intervene sooner?

In Poland, medical personnel caught performing illegal abortions can risk losing their medical license, and face criminal penalties such as imprisonment for up to 3 years (Gajewski, 2020). When journalist Dore van Duivenbode documented the abortion conflict in her documentary, “Forbidden Abortion in Poland,”she spoke with a Polish gynecologist practicing in Germany. The gynecologist, who remained unnamed for privacy reasons, claimed that gynecologists practicing in Poland are subject to a witch hunt every time a pregnancy is terminated. The Medical Board investigates whether the abortion was justified, and if there is even a slight inkling of evidence suggesting otherwise, then their entire career is in jeopardy. As a result, most gynecologists will refuse to perform abortions, even if they are legal, because they don’t want to subject themselves to this type of scrutiny.

Figure 13: "Sex is not a crime: the women protesting Poland's new abortion law"

As a result, most women are forced to seek abortions elsewhere, whether it be abroad or underground. Although abortion remains illegal, 75% of abortions still take place in Poland explained the interviewee; “you can get an abortion anywhere in Poland except at the doctor’s office” (“Forbidden Abortion in Poland”). They are performed by shopkeepers, lumberjacks, mechanics, or anyone looking to make some extra cash. An abortion performed by an unqualified individual in an unsanitary environment can result in serious complications to the woman’s reproductive health. Many women who travel abroad also seek medical attention for stomach ulcers and severe cramps as a result of these botched procedures because going to a clinic in their hometown would raise a lot of red flags (“Forbidden Abortion in Poland”). Annually, up to 150,000 abortions are performed in Poland illegally, with 15% resulting in death of the woman (Roache, 2019). As a result, non-profit organizations such as Abortions Without Borders work to raise funds for underprivileged women to obtain safe abortions in neighboring countries (The Guardian).

Lets Talk About (Safe) Sex

The irony behind Poland’s attitudes towards sex is that from an outsider perspective you would assume that Polish society is relatively open to conversations about sex based on mainstream media. In April of 2021, Netflix released the Polish series Sexify which tells the story of three university students attempting to create an application that can enhance the female orgasm. All three women are different in terms of personality, interests, and values but throughout the trajectory of the show they develop confidence in their sexuality (Netflix).

Figure 14: Sexify Official Trailer

The depiction of various erotica throughout the scenes makes Poland seem like a progressive society, but that couldn’t be farther from the truth. Conversations pertaining to sex, abortion, and contraception remain taboo, especially amongst the older generations. Many women who obtain abortions describe it as lonely process, as they tell their families that they are simply going on vacation or have a mandatory business trip (“Forbidden Abortion in Poland”). In public schools, children are exposed to “Family Life” classes where students learn about family planning and the innate roles of the man and woman in the home (GrupaPonton). These classes are introduced as early as primary school, and then in secondary school boys and girls are separated into different cohorts to discuss issues pertaining to menstruation and pregnancy (for girls) and the increasing urge for sex and masturbation (for boys). This type of curriculum mainly focuses on abstinence, and fighting the urge to have sex before marriage. In some schools, this type of material is taught by members of the clergy in religious classes, where students are taught to aspire to the same standards as St. Mary and St. Joseph from the Bible (Eberts, 1998).

Figure 15: Placement of Cross in Polish classrooms

Figure 15: Placement of Cross in Polish classrooms

In 2019, the mayor of Warsaw attempted to challenge this outdated curriculum by introducing comprehensive sex education courses into public high schools (Wilczek, 2021). Topics discussed would involve safe sex, contraception, pleasure, and same-sex relations, but the initiative was quickly overruled by strong backlash from government and the clergy (Wilczek, 2021). Government officials, with influences from the Catholic Church, claim that conversations pertaining to sex are the responsibility of the parent, and should be conducted in the privacy of the home (Wilczek,2021).

Figure 16: "The Brief: MEPs vote to condemn Poland's anti-sex education bill"

The issue with an inadequate sex education curriculum is that it contributes to an increase of unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. Women, particularly from poorer, rural areas, don’t have the knowledge or access to reliable methods of contraception resulting in unwanted pregnancies. Furthermore, women are dissuaded from using hormonal contraceptives such as the combination pill or intrauterine device (IUD) under the false pretext that these methods can decrease the chances of getting pregnant in the future (Margolis, 2017). As a result, the government limited access to emergency contraceptives by requiring women to obtain a medical prescription prior to purchase (Margolis, 2017). This causes many women to miss the 72-hour period because they are unable to acquire a doctor appointment early enough within the mandatory window (Margolis, 2017). Women shouldn’t be shamed for having sex, instead they should be provided with the necessary services to be in control of their sex lives.

What does the European Union have to say?

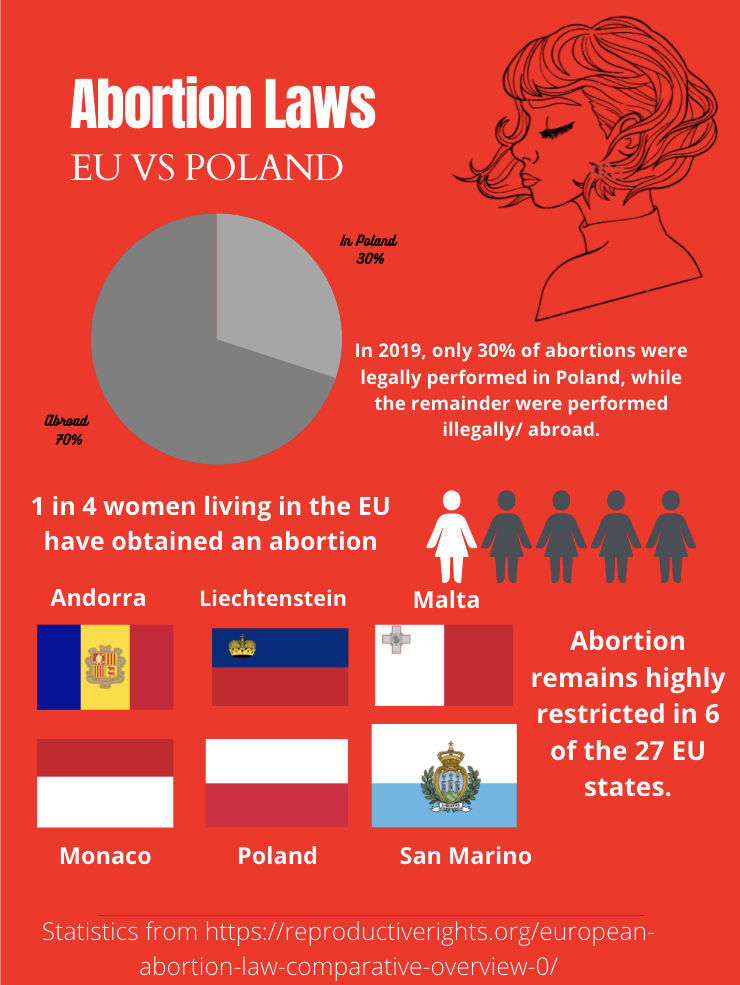

As an institution, the European Union (EU) believes that each member country should legalize abortion upon request, at least during the first trimester of pregnancy. In instances where the pregnancy poses a danger to the women’s health or life further along the pregnancy, then abortion should be taken into consideration to protect the woman (“Center for Reproductive Rights”). However, this isn’t necessarily the case for all EU states. Across Europe, 41 of 47 countries have legalized abortion upon request, and 39 of these states have legalized it without the need to provide a documented reason (“Center for Reproductive Rights”). Only 6 European countries maintain highly restrictive abortion laws and do not allow abortion upon request. These include Andorra, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, Poland, and San Marino ( see Figure 17)

Figure 17: Abortion in the European Union. See following paragraphs for description.

Figure 17: Abortion in the European Union. See following paragraphs for description.

Although the EU highly criticizes Poland’s near-total abortion ban, it has no jurisdiction over regulating abortion rights within a member state. Decisions pertaining to abortion legislation are independent of EU influence (Euronews, 2021). As a result, sovereignties have the autonomy to instate mandatory waiting periods, counseling, distress requirements, third party authorization, or refusals of care on ethical grounds (“Center for Reproductive Rights”). However, under circumstances where commitments established under international law are challenged, then the EU has the responsibility to intervene (Euronews, 2021). As a result, this past November the European Parliament’s Women’s Rights and Gender Equality Committee approved a resolution condemning Poland’s ban on abortion (Martuscelli, 2021). This resolution was proposed after the death of two Polish women who died from septic shock after the failure of doctors to conduct a potentially life-saving abortion (Martuscelli, 2021). Although the resolution has no legal authority to overturn the Polish bans, it reaffirms the EU as a supporter of the Women’s Movement.

Maintaining Abortion Laws in the U.S.A.

Similar to the EU, the United States has legalized abortion on a federal level after the monumental Roe v. Wade (1973) decision that established a woman’s legal right to an abortion. The courts ruled that a woman’s right to obtain an abortion is protected by the privacy rights guaranteed by the 14th amendment and U.S. Constitution (HISTORY). However, now nearly 40 years after the ruling, Norma McCorvey (Jane Roe) seems to have experienced a change of heart from being a pro-choice activist in her 30s to a born-again Christian and pro-life activist in her 40s (Leonhardt, 2021). McCorvey’s new perspectives on abortion pose a threat to the sanctity of Roe v. Wade as many southern states attempt to overturn the ruling and implement strict restrictions.

Figure 18: Norma McCorvey photographed with attorney, Gloria Alfred, in 1989

Figure 18: Norma McCorvey photographed with attorney, Gloria Alfred, in 1989

At the forefront of this debate is Texas, housing the country’s most restrictive abortion laws, outlawing all abortions after approximately 6 weeks of pregnancy (Leonhardt, 2021). Similarly, 11 (Ohio, Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri, Alabama, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Texas) states under the Bible Belt have proposed heartbeat laws in 2018, which outlaw abortion procedures in instances where the fetuses heartbeat is detected on an ultrasound (Leonhardt, 2021). These restrictions are problematic given that most women don’t even realize that they are pregnant until 6 weeks after gestation, and that is typically when the fetal heartbeat is first detected. This imposes a near total ban on abortion in the Southern states.

If Texas successfully challenges Roe v. Wade, then there will be an enormous chasm between the southern and northern states on abortion accessibility. Currently, most women have to travel an average of 42.54 miles to reach the nearest abortion clinic in their state, as these resources are mainly available in urban settings (Bearak, 2017). Furthermore, if southern states refuse to use state funding to finance abortion clinics, then these resources will be even more scarce, especially for women living in rural areas

The obstacles faced by women seeking to obtain abortions are depicted in the movie UNPREGNANT, which documents the journey of a young woman needing to travel hundreds of miles to the nearest abortion clinic. In the movie, Veronica, engages in safe sex with her partner, but the condom breaks resulting in an unwanted pregnancy. Under Missouri state law, the minor is required to obtain parental consent, which is challenging given her family’s strict, religious background. The overarching message of the film is that sometimes things go wrong during sex, even when protective measures are used, but that shouldn’t force teenage girls into motherhood.

Figure 19: UNPREGNANT Official Trailer

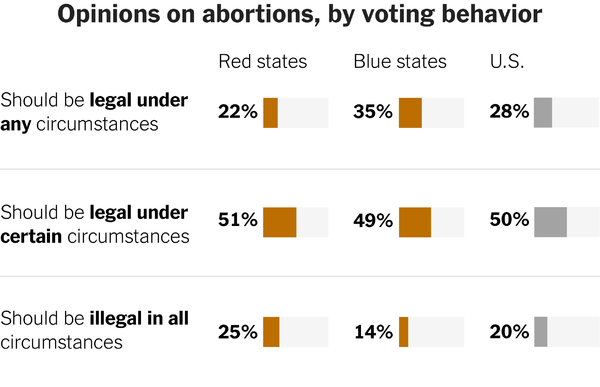

Furthermore, the need for women to travel to northern states for abortion procedures will limit the availability of reproductive resources for women living in those states. Figure 20 breaks down attitudes towards abortion across the country depicting that 50% of the U.S. agree that abortion should be legal under certain circumstances. The statistics confirm that the attitudes towards abortion are more conservative in red states as opposed to blue states. The overarching consensus is that more individuals believe that abortion should be legal (28%), rather than illegal under all circumstances (20%). The fight for abortion is not an isolated incident pertaining to Poland, but is experienced throughout the world as women’s rights continue to be challenged on the basis of religion.

Figure 20: Opinions on abortions, by voting behavior

Figure 20: Opinions on abortions, by voting behavior

Where do we go from here?

The current humanitarian crisis in Poland is about much more than abortion. It depicts the dangers of a divided society, where the ideals of the minority shape the lives of the majority. Members of the LGBTQ+ community are unable to peacefully protest without being attacked by radical, military groups. Women are dying on operating tables because of an inadequate healthcare system that repeatedly fails them. Younger generations, unwilling to compromise their freedoms, are forced to leave their friends and families seeking political refuge overseas. These issues are real, and they are happening in our modern world. As a Polish-American woman, these issues are especially alarming to me because I could have been any of those young women at the front lines of the Women’s Movement being doused in tear gas and attacked by the militia. It’s simply unfair that I get the privilege of living in a country where I have control over my reproductive rights, whereas the lives of women back home are determined by a corrupt government and outdated institutions.

As a result, I consider this capstone as my contribution to the Women’s Rights Movement, hopefully, readers are able to learn and empathize with the current political situation taking place in Poland. Despite the ongoing obstacles, I choose to remain optimistic. More and more young people are using their social media platforms to speak out against such atrocities, and voting in national and local elections. In due process, we will be able to replace corrupt politicians with progressive leaders, especially women, who have been impacted by these reproductive restrictions. As women, it is our responsibility to unite and fight for equity in all sectors of society, including healthcare.

Works Cited

Bearak, Jonathan M. Burke, Kristen Lagasse, & Jones, Rachel K. (2017). Disparities and Change over time in distance women need to travel to have an abortion in the USA: a spatial analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 11(2), e493-e500, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30158-5

Eberts, Mirella W. (1998). The Roman Catholic Church and Democracy in Poland, Europe-Asia Studies, 50(5), 817-842, https://www.jstor.org/stable/153894

Euronews. (2021). EU Criticizes Poland’s abortion ban as it reminds member states to ‘respect fundamental rights’, EuroNews, https://www.euronews.com/2021/02/24/eu-criticises-poland-s-abortion-ban-as-it-reminds-member-states-to-respect-fundamental-rig

Fitzsimons, Tim. (2020). Poland re-elects president who creates ‘dangerous’ society for gays, advocates say, NBCNews, https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/poland-re-elects-president-who-created-dangerous-society-gays-advocates-n1233684

Forbes, Phil. Polish Women- How Polish Girls Have Shaped Their Beautiful Country, Expats Poland, https://www.expatspoland.com/polish-women/

History.com editors. (2019). Roe v. Wade, HISTORY, https://www.history.com/topics/womens-rights/roe-v-wade

Kubow, Magdalena. (2013). The Solidarity Movement in Poland: Its History and Meaning in Collective Memory, The Polish Review, 58(2), 3-14, https://doi.org/10.5406/polishreview.58.2.0003

Leonhardt, David. (2020). The Mushy Middle, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/27/briefing/abortion-texas-roe-v-wade.html

Mackintosh, Eliza. (2020). As Poland defies ‘European values,’ women resist on streets and online, CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/22/europe/poland-protest-abortion-lockdown-intl/index.html

Margolis, Hillary. (2017). In Poland, Being a Woman Can Be Bad for Your Health, Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/06/poland-being-woman-can-be-bad-your-health#

Martuscelli, Carlo. (2021). European Parliament set to condemn Poland’s abortion rules, POLITICO, https://www.politico.eu/article/european-parliament-poland-abortion-ban/

Mortensen, Antonia & Reuters, (2021). Poland puts new restrictions on abortion into effect, resulting in near-total ban on termination, CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/28/europe/poland-abortion-restrictions-law-intl-hnk/index.html

Picheta, Rob. (2020). Poland moves to near-total ban on abortion, sparking protests, CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/22/europe/poland-abortion-fetal-defect-ruling-intl/index.html

Pronczuk, Monika & Santora, Marc. (2021). Andrzej Duda Wins 2nd Teen After Tight Race in Poland, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/13/world/europe/poland-president-elections-Andrzej-Duda.html

Reuters. (2021). Death of pregnant woman ignites debate about abortion ban in Poland, CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2021/11/07/europe/poland-abortion-ban-march-intl/index.html

Roache, Madeline. (2019). Poland is Trying to Make Abortion Dangerous, Illegal, and Impossible, Foreign Policy, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/08/poland-is-trying-to-make-abortion-dangerous-illegal-and-impossible/

Ścisłowska, Monika. (2020). Liberal Warsaw mayor injects suspense into presidential vote, ABCNews, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/liberal-warsaw-mayor-injects-suspense-presidential-vote-70978871

Sex Education in Poland, Grupa Ponton, https://ponton.org.pl/en/sex-education-in-poland/

Staff and agencies in Warsaw. (2020). Poland rules abortion due to foetal defects unconstitutional, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/22/poland-rules-abortion-due-to-foetal-defects-unconstitutional

Wilczek, Maria. (2021). Polish government to help parents stop “corrupting” sex education in schools, Notes from Poland, https://notesfrompoland.com/2021/11/26/polish-government-to-help-parents-stop-corrupting-sex-education-in-schools/

(2021). European Abortion Law: A Comparative Overview, Center for Reproductive Rights, https://reproductiverights.org/european-abortion-law-comparative-overview-0/

(2021). Emergency Contraception Availability in Europe, European Consortium for Emergency Contraception (ECEC), https://www.ec-ec.org/emergency-contraception-in-europe/emergency-contraception-availability-in-europe/

Mediography

Title Page: Chapman, Annabelle & Morris, Loveday. (2020). Women’s rights groups, Polish nationalists face off as churches become flash points in protests over abortion, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/womens-rights-groups-polish-nationalists-face-off-as-churches-become-flash-points-in-protests-over-abortion-law/2020/10/30/76c10c32-19f6-11eb-8bda-814ca56e138b_story.html

Duivenbode, Dore van. (2020). Forbidden Abortion in Poland, VPRO Documentary, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rIQ0PdaRhpk&t=300s

Figure 1: Bordsen, John. (2012). A patch of Poland in N.Y.C. The Philadelphia Inquirer, https://www.inquirer.com/philly/living/travel/20121021_A_patch_of_Poland_in_N_Y_C_.html

Figure 2: Wawel Castle. https://krakow.wiki/wawel-castle/

Figure 3: Our Lady of Czestochowa, http://www.polishamericancenter.org/Czestochowa.htm

Figure 4: Glinski, Mikolaj. (2015). Solidarnosc: Poland Word by Word, Culture.pl, https://culture.pl/en/article/solidarnosc-poland-word-by-word

Figure 5: Reuters & Israel Hayom. (2019). Paper sold at Polish parliament explains ‘how to recognize a Jew’, Israel Hayom, https://www.israelhayom.com/2019/03/15/paper-sold-at-polish-parliament-explains-how-to-recognize-a-jew/

Figure 6: 1791 Constitution Stock Photos and Images (487), Alamy, https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/1791-constitution.html

Figure 7: File: President Trump Meets with President Duda of Poland, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Trump_Meets_with_President_Duda_of_Poland_(48052051462).jpg

Figure 8: Gera, Vanessa. (2019). Mayor joins pride parade amid Poland’s anti-LGBT campaign. Toronto Star, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/europe/2019/06/08/warsaws-pride-parade-comes-amid-fears-and-threats-in-poland.html

Figure 9: BBC News (2020). Poland’s conservative President Duda re-elected, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caN6RfeWd2A

Figure 10: BBC News (2020). Mass Protests in Poland Against Law Banning Almost All Abortions, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crGnIkN4RBI

Figure 11: Pronczuk, Monika. (2020). Why are there Protests in Poland? The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/27/world/europe/poland-abortion-ruling-protests.html

Figure 12: Euronews. (2021). ‘No more women should die’: MEPs slam Poland’s near-total abortion ban, Euronews, https://www.euronews.com/2021/11/11/no-more-women-should-die-meps-slam-poland-s-near-total-abortion-ban

Figure 13: The Guardian. (2020). ‘Sex is not a crime’: the women protesting Poland’s new abortion law, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VDKjCOFzVD0

Figure 14: Domalewski, Piotr. (2021). Sexify, Official Trailer, Netflix, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DDpoRK3dlHQ

Figure 15: Bretan, Juliette. (2020). Polish bishop let priest accused of sex abuse keep teaching children- Vatican orders investigation. Notes from Poland, https://notesfrompoland.com/2020/09/13/polish-bishop-let-priest-accused-of-sex-abuse-keep-teaching-children-vatican-orders-investigation/

Figure 16: Euronews. (2019). The Brief: MEPs vote to condemn Poland’s anti-sex education bill, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f43N7G4nYIk

Figure 17: Infographic information taken from; (2021). European Abortion Law: A Comparative Overview, Center for Reproductive Rights https://reproductiverights.org/european-abortion-law-comparative-overview-0/

Figure 18: Leonhardt, David. (2020). The Mushy Middle, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/27/briefing/abortion-texas-roe-v-wade.html

Figure 19: Goldenberg, Rachel Lee. (2020). UNPREGNANT Trailer, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WFLhX8OIOC0&t=1s

Figure 20: Leonhardt, David. (2020). The Mushy Middle, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/27/briefing/abortion-texas-roe-v-wade.html