Santa Maria Novella Station: Resituating Florence's Station in its Fascist Context

Abstract

Santa Maria Novella Station in Florence, Italy was designed by Italian architecture collective Gruppo Toscano. The station’s construction (1934-36) was controversial as it prominently introduced modern architecture into Florence’s historically sensitive city center. However, the station came to be heralded as a masterpiece of Italian Rationalism, an Italian architectural movement in the first half of the 20th century, as it converged Rationalist principles of functionality and geometry with the style of Florence’s historic architecture. Amidst its acclaim, a less convenient aspect of Santa Maria Novella Station has slid from view. The station was a product of Benito Mussolini’s Italian Fascist regime. Mussolini consolidated political control of Italy and established a totalitarian state from 1922 to 1943. Due to the reconstruction policies implemented in Italy following World War II, Fascist-era monuments have persisted into the 21st century. Moreover, they have come to hold significance as Italian cultural and artistic heritage, while their Fascist pasts have gone largely unacknowledged. In response to the underrecognized contexts of Italian Fascist monuments in 21st century Italy, Santa Maria Novella Station will be re-situated within its Fascist past. A review of the station’s controversial debut will be used to illustrate how such monuments have been discussed in isolation from their Fascist contexts in scholarly literature. To address this literature gap, the station’s Fascist architectural elements will be drawn out and situated within the Mussolini regime’s wider use of architectural devices to propagate its legitimacy. From this backbone, the underlying questions of why Fascist buildings remain in Italy and how they are remembered by contemporary Italians will be examined. Finally, the risks posed by the persistence of Fascist monuments will be considered in the current Italian political landscape.

Keywords

Santa Maria Novella Station, Florence, Italy, Rationalism, Fascism, Architecture, Memory

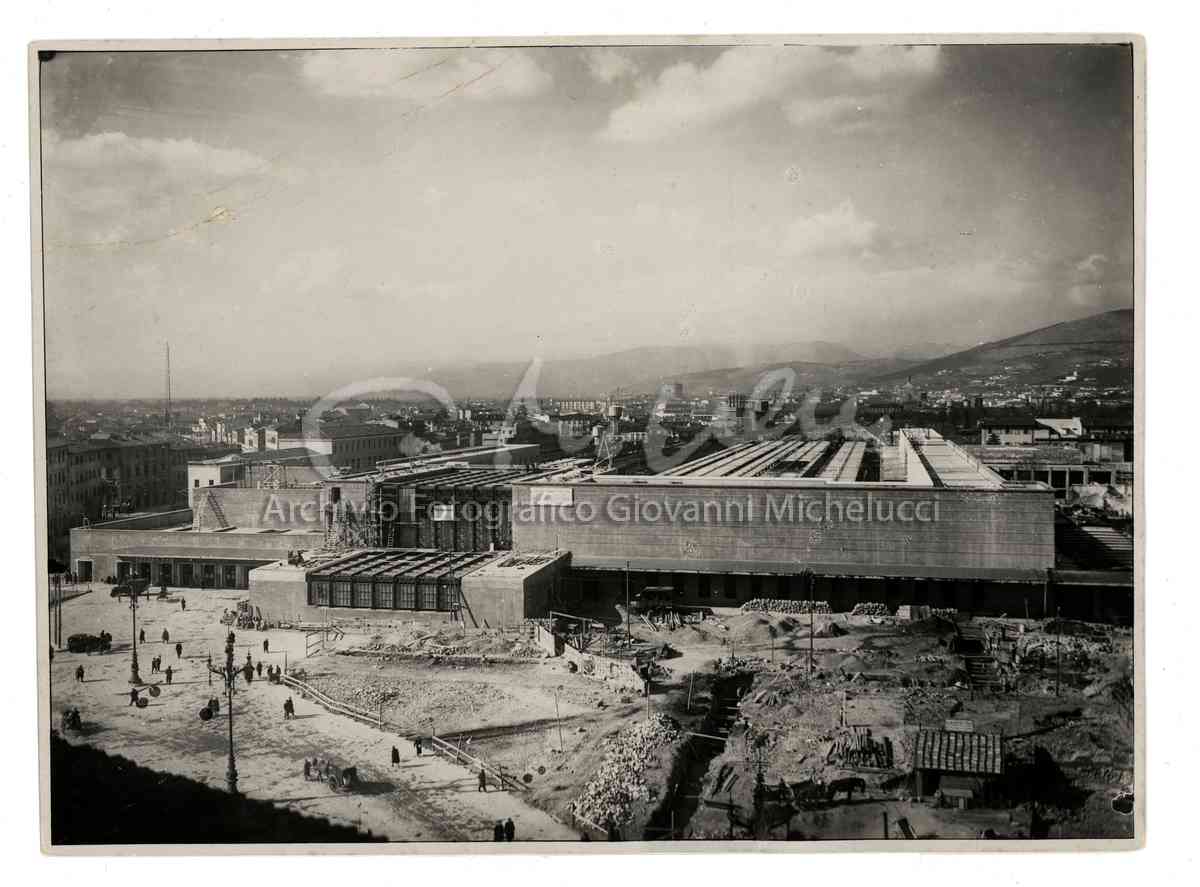

2. Firenze Santa Maria Novella Station under construction (Image: Archivio Fondazione Michelucci).

2. Firenze Santa Maria Novella Station under construction (Image: Archivio Fondazione Michelucci).

Introduction

Arriving at Santa Maria Novella Station, you’re undoubtedly anxious to finally experience the “Renaissance Disneyland” that is Florence, Italy. You step off the train and hurry down the platform through the main concourse, trying to orient yourself amidst the flurry of travelers. You walk through the ticket hall and reach the exit where, blinded by the Italian sun, you stumble out into the chaos of Florence.

The encounter with the station itself was likely brief. Ultimately, it's another train station, another leg of the journey. Your inclination is not to linger, naturally wanting to settle into your accommodations before cramming your brain with Renaissance art and prowling the medieval streets.

But did you happen to take note of anything regarding the station’s architecture? The marble floors you walked across? The glass ceiling? The monumental ticket hall? Did you happen to look back at the station once you left? Did you notice anything peculiar about its shape or perhaps a contrast from the grandiose interior to the humble stone exterior? Why is it that you are ushered into the historic center of Florence through a modernist building in the first place? If you didn't notice these things, or think to notice, that is the point, the station is intended to avoid calling attention to itself. But it begs the question: What else about the station also may have been able to evade your attention?

Firenze Santa Maria Novella Station was constructed from 1934 to 1936. It was designed by Gruppo Toscano, led by Italian architect Giovanni Michelucci (Watkin 630). The building’s purpose was to provide Florence with a modern railway station to meet the demand of its expanding population in the early 20th century, replacing its predecessor, Maria Antonia Station (Rendon). Santa Maria Novella Station continues to service over 50 million passengers annually (FS Italiane). The station has become recognized as an innovative work of Italian Rationalism, an Italian architecture movement in the first half of the 20th century, as it converged the movement’s principles of functionality and geometric rigor with the style of Florence’s historic architecture. However, the station was fraught with controversy in the 1930s due to its introduction of the modern architectural style at a historically sensitive junction of Florence’s city center.

This examination of Santa Maria Novella Station began while I was studying in Florence in 2023. I wanted to understand how and why Santa Maria Novella Station, a pivotal work of Italian modern architecture, came to reside in the historic center of Florence, a city known for its Renaissance history and art. Moreover, I was interested in analyzing how the modern architecture of the station “interacted” with the medieval built environment of Florence. By interacted, I mean how the station fit in within its historic urban context. However, the deeper into this analysis I went, the more the history Santa Maria Novella Station continued to spring up.

The station was built under Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime, which ruled Italy from 1922 to 1943. The Fascist party took control of the Italian state with its March on Rome in 1922. Mussolini consolidated political authority of the state to establish a totalitarian regime which controlled every realm of Italian life (Oxford Reference). Architecture and urban planning were primary means by which the regime asserted its ideological agenda. The inconvenient history of Italy’s totalitarian regime continued to stare me in the face as I analyzed Santa Maria Novella Station from a strictly architectural lens. Ultimately, I could no longer continue to ignore the station’s role in Italy’s Fascist past, and instead chose to dive directly into this history to relink the station and its architecture with its original context.

The structure of discussion will reflect the evolution of my analysis of the station. Beginning with the controversy of Santa Maria Novella Station and its historically sensitive site adjacent to the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, this analysis will examine the station’s architectural design as a reaction to its historic site.

3. Frecciarossa high speed train arriving at Santa Maria Novella Station (Video by the author).

3. Frecciarossa high speed train arriving at Santa Maria Novella Station (Video by the author).

From this site-specific view, I will consider how and why the station’s links to Italian Fascism have been overlooked and ignored across scholarly literature of Italian architecture. With this literature gap established, the discussion will extensively analyze the Fascist architectural elements that remain embedded in Santa Maria Novella Station. With Santa Maria Novella Station reframed as a Fascist building, I will explore why Italy’s Fascist monuments remain standing in the 21st century. The significance of these structures will be established through a discussion of Italian memory of Fascist monuments. This memory will be examined through the cases of Predappio and Bolzano to lay out how such monuments have been dealt with in the 21st century. Finally, the relevance of these monuments in contemporary Italy will be established by evaluating the risks of allowing them to go unacknowledged in the context of the current Italian political climate.

What are the architectural and urban planning legacies of the Italian Fascist regime on Italian cities, particularly Florence? How and why do Italian Fascist monuments endure in 21st century Italian cities? What role do Fascist monuments play in the collective memory of contemporary Italians, if any? What is at stake if such monuments continue to go unacknowledged in the 21st century?

Santa Maria Novella Station has become a site of architectural and cultural heritage for contemporary Florentines and Italians. However, since the fall of the Italian Fascist regime, the station has been decontextualized and dehistoricized, allowing its Fascist links to go unacknowledged. The case of Santa Maria Novella Station is representative of the larger processes of ignorance and avoidance of the embedded Fascist histories of such monuments throughout Italy. The continued persistence of these monuments offers neo-Fascist groups, like Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, to draw on their symbolic power to assert their ideological agenda. The ultimate goal of this work is to prompt a critical reevaluation of Santa Maria Novella Station, and Italian Fascist buildings more generally, to address the lack of active acknowledgement of its Fascist origins by Italians and tourists alike. While many visit Florence for its Renaissance history, one ought not to forget or plead ignorant to the less convenient truths of its modern past.

4. Santa Maria Novella Station (Video by the author).

4. Santa Maria Novella Station (Video by the author).

Historically Charged Site

5. Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Upper facade designed by Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti (Photo by the author).

5. Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Upper facade designed by Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti (Photo by the author).

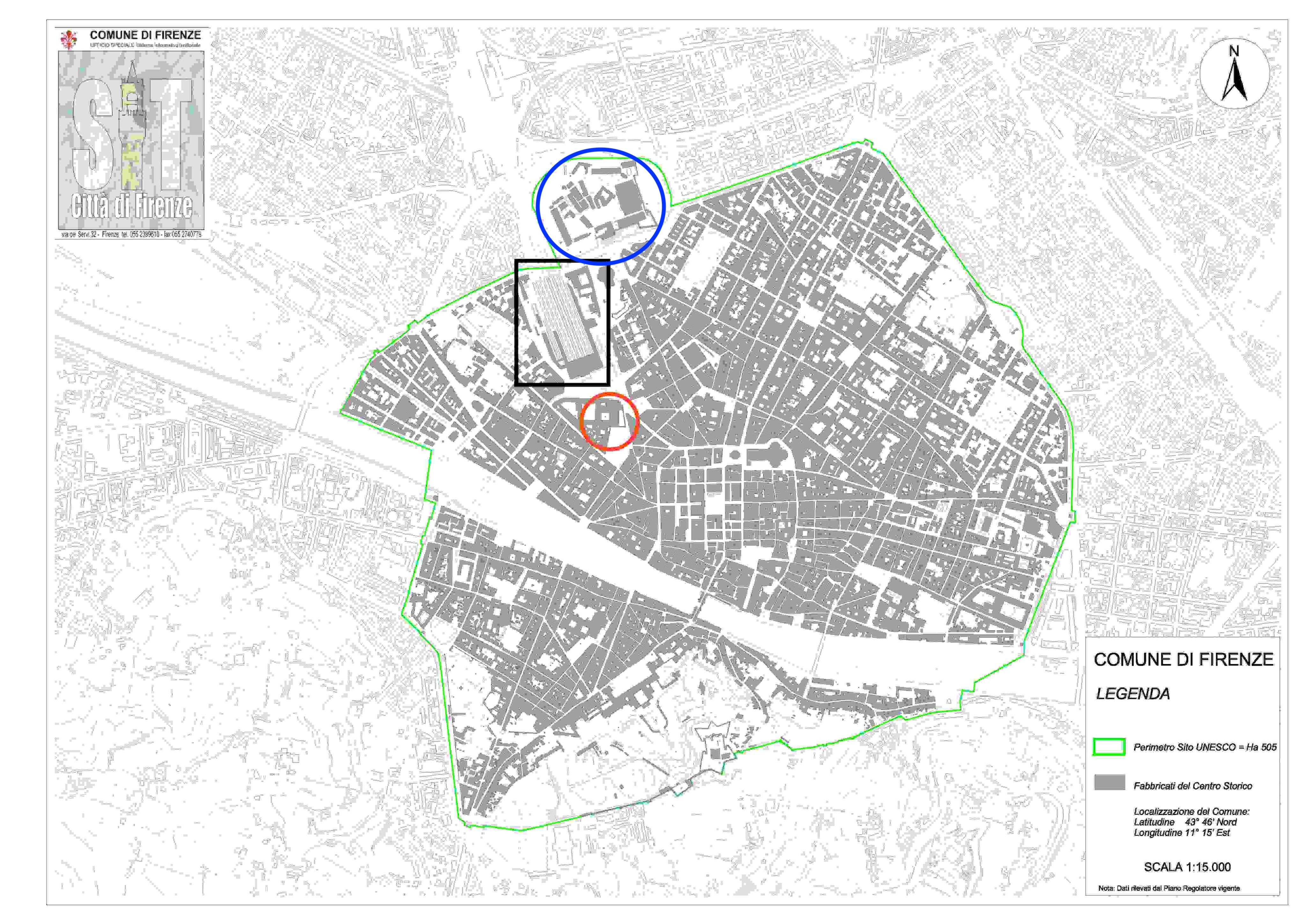

The controversy surrounding the realization of Santa Maria Novella Station stemmed from its historically charged site in Florence’s city center. The station’s site is adjacent to the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, the upper facade of which, designed by Leon Battista Alberti, is a significant work of Renaissance architecture. To the northeast of the station's site is the 16th century Fortezza da Basso. Wedged between these cornerstones of Florentine Renaissance architecture, there is a great historic sensitivity embedded in this specific site (Rendon; Meeks 151).

6. Fortezza da Basso (Image: Città Metropolitana di Firenze).

6. Fortezza da Basso (Image: Città Metropolitana di Firenze).

To establish the significance of the site more concretely, it is necessary to further explain the importance of Alberti and his Santa Maria Novella facade. Alberti, a Renaissance theorist, wrote three theoretical treatises on painting, “De pictura,” sculpture, “De statua,” and architecture, “De re aedificatoria.” De re aedificatoria is considered the most significant as it was the first comprehensive treatise on Renaissance architecture as well as the first to fully address classical architecture since Vitruvius in Ancient Rome (the only surviving ancient treatise on architecture). As such, it outlines key concepts of Renaissance architecture. Most notably was Alberti’s concept of concinnitas, the harmony of a composition, also understood as proportionality. He outlined that each element of an architectural composition must be related via proportional relationships, creating such harmony (Davies and Hemsoll).

7. Map of Florence history city center (green line) (Image: UNESCO). Santa Maria Novella Station (black rectangle); Basilica of Santa Maria Novella (red circle); Fortezza da Basso (blue circle).

7. Map of Florence history city center (green line) (Image: UNESCO). Santa Maria Novella Station (black rectangle); Basilica of Santa Maria Novella (red circle); Fortezza da Basso (blue circle).

Santa Maria Novella’s significance derives from this text as it is considered to be one of the most direct correlations between Alberti’s theory and realized architecture. Put most simply, the facade exemplifies the proportional relationships Alberti wrote of. For example, the total width of the facade is equivalent to its total height, its two storeys are the same height, and the lower storey is twice the width of the upper (Davies and Hemsoll). This discussion is intended to emphasize the historical significance of Santa Maria Novella Station’s site in Florence, and in doing so, emphasize the drastic shift in architectural style caused by the introduction of the station.

8. View of Piazza Santa Maria Novella (Video by the author).

8. View of Piazza Santa Maria Novella (Video by the author).

While the new station was to be built on the site of the previous Maria Antonia Station, its design was under intense scrutiny given that it drastically departed from its predecessor's neoclassical style and introduced modern architecture at a critical juncture of the city's historic center (Rendon). The significance of this shift is further exacerbated given the building's key role as the primary station in Florence’s city center. The station is literally front and center. It is highly visible given its location and function – making it a site of frequent engagement by travelers and locals alike – further raising the architectural stakes.

Station Design

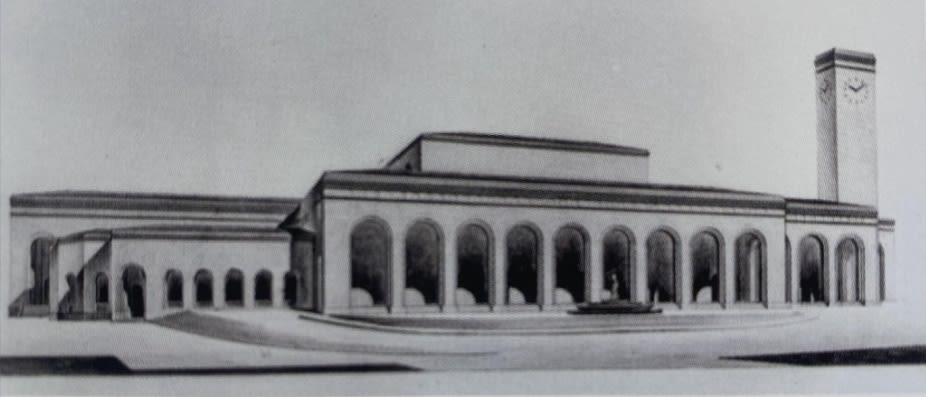

The initial design proposal for the new station by Angiolo Mazzoni in 1932 was rejected as its classical references were considered too monumental and therefore confrontational towards the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. It featured an arched portico across its main facade, evoking Roman grandeur. Furthermore, its clock tower rivaled the verticality of Santa Maria Novella’s bell tower across the street, drawing them into direct vertical conflict (Simons; Andreotti 471).

10. Santa Maria Novella Station initial design proposal by Angiolo Mazzoni (Image: Rendon).

10. Santa Maria Novella Station initial design proposal by Angiolo Mazzoni (Image: Rendon).

In 1933, a design competition for the new station was launched. The challenge at hand was to find a balance between designing a modern, functional building, adhering to the architectural concepts of Rationalism, to serve the city’s transportation needs while also remaining sensitive to the historically charged surroundings (Ward 37; Cisternino).

Rationalism, briefly, can be understood as the concept of architectural design deriving from the functional need of a building. As a result, Italian Rationalist architecture was primarily based on basic geometric volumes, with no decoration or unnecessary elements (Watkin 628). One primary example is the Casa del Fascio (1933-36) in Como, Italy by Giuseppe Terragni. The stylistic elements of Rationalism were a major departure from Florence's historic architectural environment.

11. Main facade Casa del Fascio, Como (Image: Nodo libri Como).

11. Main facade Casa del Fascio, Como (Image: Nodo libri Como).

The winning station design came from Tuscan architecture collective Gruppo Toscano, led by architect Giovanni Michelucci. Gruppo Toscano designed the station to merge Rationalist architectural ideas with elements reflective of Florence's historic buildings.

"Of modest height, no more than fifteen meters, it neither emerges above the surrounding rooftops, nor does it assume an improper monumental stance. Its form closely follows its intended function, and the slightly indented grooves of its stone walls are sensitive, in keeping with certain features of Florentine architecture."

To cope with the historic significance of the station’s site, Gruppo Toscano realized the station in a manner that did not draw attention to itself, achieved through its verticality (or lack thereof), historic references, and materials. First, the architects decided to create a station that expanded horizontally as opposed to vertically, literally creating a low profile. This crucial decision prevented the station from competing with the height of other significant Florentine buildings, especially Santa Maria Novella (Simons). Moreover, the building's horizontal profile evoked a medieval wall, like those that had surrounded the city until the late 19th century, further grounding the station's design in Florence's historic urban form (Rendon).

Furthermore, the building’s facade was constructed with “pietra forte,” a locally abundant Tuscan stone. The choice of material was crucial. Historically, pietra forte was used extensively throughout Florence to construct many of its buildings including the Basilica of San Lorenzo and, of course, the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. This decision further allowed Santa Maria Novella Station to maintain an “understated profile” in relation to its historic surroundings, as the yellow-brown stone facade blended homogeneously with the apse of Santa Maria Novella across the street and within the city more generally (Andreotti 471). With these decisions, Gruppo Toscano was able to realize a modern architectural design that was sensitive to the historically charged environment of Florence.

12. Drawing of Santa Maria Novella Station facade (Image: Archivio Fondazione Michelucci).

12. Drawing of Santa Maria Novella Station facade (Image: Archivio Fondazione Michelucci).

13. Santa Maria Novella Station front facade (Image: Archivio Fondazione Michelucci).

13. Santa Maria Novella Station front facade (Image: Archivio Fondazione Michelucci).

14. Detail of pietra forte on Santa Maria Novella Station facade (Photo by the author).

14. Detail of pietra forte on Santa Maria Novella Station facade (Photo by the author).

15. View of Santa Maria Novella Basilica from Santa Maria Novella Station. This photo demonstrates their homogeneity deriving from their primary material, pietra forte (Photo by the author).

15. View of Santa Maria Novella Basilica from Santa Maria Novella Station. This photo demonstrates their homogeneity deriving from their primary material, pietra forte (Photo by the author).

16. Detail of Santa Maria Novella Station, pietra forte facade (Image: Kommel).

16. Detail of Santa Maria Novella Station, pietra forte facade (Image: Kommel).

17. Detail of San Lorenzo Basilica, 15th C, pietra forte facade (Image: Kommel).

17. Detail of San Lorenzo Basilica, 15th C, pietra forte facade (Image: Kommel).

Omission of Fascist History

This case study has provided a brief overview of Santa Maria Novella Station’s historically sensitive site and design as it was taught to me in Italy. However, this is not the full story. The scope of the station’s analysis to this stage has omitted key context to its construction and design. This omission is reflective of the exclusion of the historic context of Rationalist architecture embedded in scholarly literature. Ultimately, Rationalist architecture has another element to its definition: its service to and deployment by Mussolini’s Fascist regime. Rationalist architecture therefore can be effectively defined as Fascist architecture.

Diane Ghirardo’s essay “Italian Architects and Fascist Politics: An Evaluation of the Rationalist's Role in Regime Building,” brings to light the multitude of links between Italian Rationalist architecture and Italian Fascist regime that have been intentionally avoided in Italian architectural scholarship. Scholars have attempted to explain away, excuse, ignore, and avoid the blatant Fascist contexts and ideological parallels embedded within Rationalist buildings (Ghirardo 109). One particularly potent point Ghirardo makes is the effort of such scholars to ignore

...the Fascism of the architects altogether, claiming that a building can be studied apart from its historical setting, intended use, and patronage, and that a formal analysis in relation to architectural movements throughout the world provides complete and sufficient understanding. However, state-funded buildings constructed during the Fascist period were intended for particular settings designed to serve certain functions; because they had patrons with definite political programs, they could not but serve as vehicles of that political ideology.

While the above case study examined Santa Maria Novella Station within the historical background of its site, the analysis primarily took place from an aesthetic perspective and did not recognize the Fascist intentions underlying its construction.

Other attempts to explain away such parallels include excusing Fascist architects as “blind, young, misled, or betrayed,” as playing “Fascist to do architecture,” or even framing them as victims persecuted by the regime (Ghirardo 109-110). This point is demonstrated by Italian architect Ernesto N Rogers’ quote on young Italian architects,

I think the basis of our error was one of philosophical confusion. We took our starting point to a syllogism that said, Fascism is revolutionary, Modern Architecture is revolutionary, therefore Rationalism must be the architecture of Fascism. As you see, the first proposition was wrong, and the consequences were thus disastrous. Fascism was no revolution.

Although architects like Rogers ultimately denounced their Fascist orientations following the collapse of the Regime, this renunciation did not rid Rationalist buildings of their Fascist intentions and contexts.

This holds true for Santa Maria Novella Station which, as we will see, was both endorsed directly by Mussolini and maintains its Fascist architectural references to the present day. However, the station’s Fascist origins are not widely acknowledged or made clear, whether that is in the station itself or by Italian scholars.

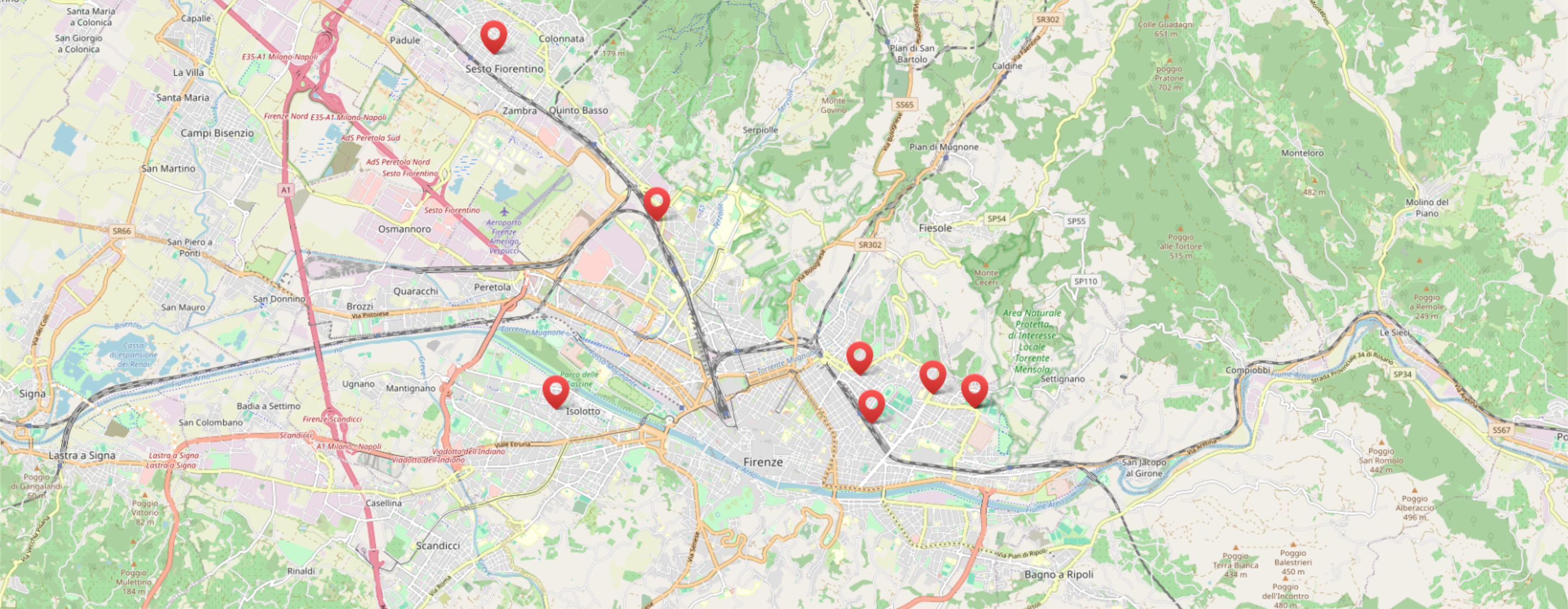

The removal of Santa Maria Novella Station from its context is illustrated by the project, “The Places of Fascism.” The project’s goal is to systematize Italian Fascist monuments into an online mapping database (Poggioli). Reviewing the map in March 2024 revealed that Santa Maria Novella Station was not included in the database, despite its Fascist origins and design elements. It appears that Santa Maria Novella Station has been able to shed its Fascist shell, and this investigation will seek to resituate it in its original context.

Furthermore, scholarly literature that references Santa Maria Novella Station typically does no more than just that. These texts situate and acknowledge the station as a Fascist building, but do not take the next steps to analyze the Fascist architectural references embedded in the station.

Such texts include those central to the development of this discussion. Hannah Malone’s “Legacies of Fascism: architecture, heritage and memory in contemporary Italy” briefly refers to the station as an instance of reuse of Fascist buildings (Malone 449). William Ward’s “Rationalism: Architecture in Italy Between the Wars,” discusses the controversy surrounding the station’s construction and design competition. His architectural analysis is limited to how Gruppo Toscano integrated Rationalism into the historic city center of Florence (Ward 37). Francesco Cianfarani’s “The Fascist Legacy in the Built Environment” focuses on Angiolo Mazzoni’s initial project. His concise reference to Gruppo Toscano’s design is also limited to its relationship with the historic Florentine architectural environment (Cianfarani 34).

Other texts make even lesser mention of the station. Diane Ghirardo’s “Italian Architects and Fascist Politics: An Evaluation of the Rationalist's Role in Regime Building” relegates the station to the footnotes as it pertained to the design competition and architect Marcello Piacentini (Ghirardo 112). David Rifkind’s “The radical politics of marble in Fascist Italy” name drops the station solely in reference to Mussolini’s comments on modern architecture (Rifkind 135).

To address the limitations of previous scholarly literature, both in terms of Fascist buildings' decontextualization and the lack of an extensive discussion of Santa Maria Novella Station's Fascist architectural elements, the following discussion will reframe these assumptions and re-establish Santa Maria Novella Station in its 20th century Fascist context. This will be achieved through an analysis of its Fascist architectural elements.

18. A review of the Places of Fascism mapping database reveals that Santa Maria Novella Station (center) is not listed as a Fascist monument. Red marks indicate a Fascist monument (Image: luoghifascismo.it).

18. A review of the Places of Fascism mapping database reveals that Santa Maria Novella Station (center) is not listed as a Fascist monument. Red marks indicate a Fascist monument (Image: luoghifascismo.it).

Italian Fascist Tactics: Architectural Design and Urban Planning

Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime used a variety of architectural and urban planning tactics to communicate its ideological program. Generally, the Fascists did not have one strict architectural identity. Rather, they drew from a variety of architectural strains to contribute to their agenda. They simultaneously made use of the modern architectural movement of Rationalism while also embracing architecture that recalled the historic styles of the Italian peninsula (Ghirardo 114).

On the historic end of the spectrum, the Fascist regime sought to communicate its authority by aligning itself with Roman antiquity through the appropriation, simplification, and decontextualization of Roman symbols, turning them into Fascist visual propaganda for the dissemination of their ideology. In urban planning terms, these strategies of appropriation and decontextualization have been called urban planning “conquest,” or the taking control of historically significant spaces in Italian cities. By controlling these spaces, the regime was able to control the past and therefore project its own interpretations of historic time and space to serve its ideological needs (Kallis 812).

This strategy was widely implemented in Rome. Roman ruins were tangible symbols the regime could reference to legitimize its authority. The regime took actions to “systematize” the city including isolating Roman monuments and demolishing their surroundings. Such acts decontextualized Roman monuments to create an idealized view of the Roman past in which to ground the regime’s aspirations to create a “third Rome” (Kallis 810-811; Fadda 725). Furthermore, with these monuments isolated, the regime could construct their own version of Rome in which Fascist architecture stood side by side with Roman remnants. Such actions were intended to legitimize the regime’s positioning as "heir" to imperial Rome.

As Salvatore Fadda put it, “Mussolini's Rome would thus be the only Rome worthy of standing among the vestiges of the imperial city to which fascist propaganda had always referred” (Fadda 725).

Simultaneously, the Fascists prominently made use of Rationalist architecture and modern infrastructure to promote its authority. Rationalism, for all its interest in function and geometric forms, was also highly interested in recalling the Italian past in its modern designs. Rationalists sought to embrace the “spirit” that pervaded both ancient Rome and the Renaissance in their contemporary works (Ghirardo 115). Ultimately, Ghirardo describes both Italian Fascism and Rationalism as “straddling...tradition and modernity” (Ghirardo 116). Rationalist projects therefore integrated historic references under the guise of modern forms. Take again the Casa del Fascio in Como. While the composition of the building derives from modern conceptions of geometry, based on the form of the square, it is also embedded with references to Roman architecture in its prominent marble cladding (Rifkind 151). In doing so, the Rationalist movement, in service to the Fascist regime, positioned itself as continuing the legacy of the great Italian civilizations and movements of the past, drawing legitimacy to its modern projects.

Moreover, the Fascist regime was responsible for constructing Italy’s modern infrastructure network. The regime constructed railway stations, post offices, schools, governmental offices, and ports (Malone 453). The implementation of modern infrastructure was and continues to be an act potent with symbolic capital. Infrastructure cannot be understood simply as an object. Rather, it has the power to capture the imagination, promising to bring the betterment of a society by offering circulation and the freedom of movement (Larkin 332-334). The Italian Fascists too sought to take advantage of the power of infrastructure. By bringing infrastructure to Italy, the Fascists could position themselves as the ones responsible for modernizing the nation. Therefore, Italy was emerging as a modernized nation thanks to the regime’s governance.

Santa Maria Novella Station: A Fascist Monument

With these strategies and parallels outlined, we must take another look at Santa Maria Novella Station’s design to peel back the references to the regime – references stemming from the regime’s desire to situate itself in continuum with imperial Rome and the Renaissance while simultaneously “straddling” the modern, Rationalist style. The station’s architecture is embedded with symbolic references to the regime. These references include the construction of a modern railway station in Florence, the use of Roman symbols, the intersection of ancient and modern materials, and its historically significant location.

First and foremost, Gruppo Toscano’s design was directly endorsed by Benito Mussolini, inextricably linking the station’s inception to the Italian Fascist regime. He stated, “I wish to point out that I am unequivocally in favor of Modern Architecture - it is absurd to even think that Fascism should not have its own architectural philosophy . . . and not have Rationalism and Functionalism on its side” (Ward 37). By endorsing the construction of a modern train station in Florence, the regime could use it for propagandistic means as "bestowing" such a benefit on Florence (Hibbert 293). Underlying this endorsement was the regime’s rollout of modern infrastructure in the state. Therefore, by funding efforts to modernize Italy’s infrastructure, the regime advanced the notion that as a result of its governance, Italy was a modernized and efficient nation. (Watkin 628, 630; Cisternino).

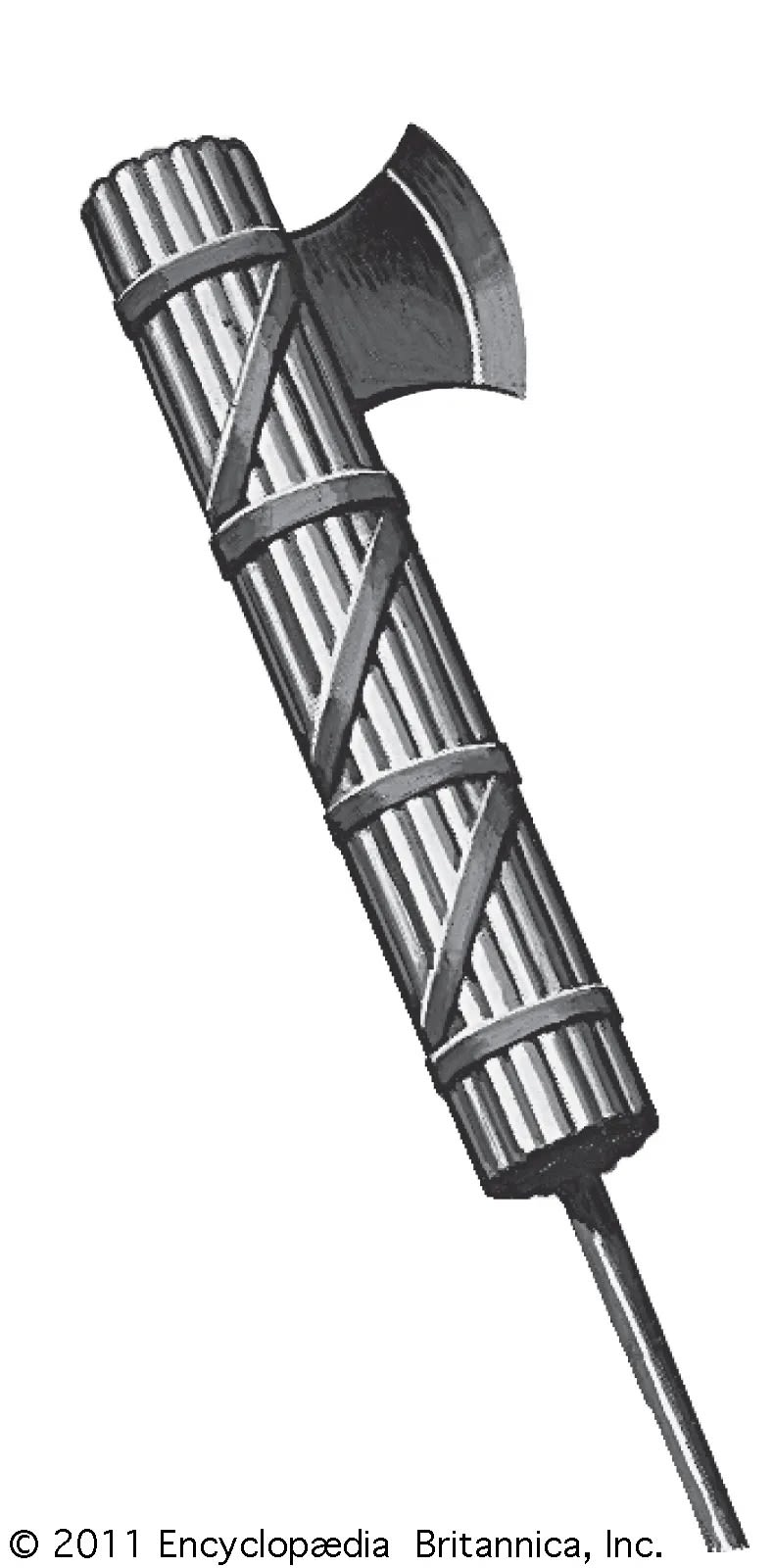

A direct symbolic reference to Roman antiquity is embedded in the main entryway of the station. The shape of the doorway was created in reference to the symbol of Italian Fascism, the fasces. The fasces is an ancient Roman military symbol, a bundle of sticks with an ax. The form of the doorway was intended to recall the edge of this ax (Cisternino). The symbol was initially used as the symbol of the Fascist party and subsequently became the symbol of the state. The selection and decontextualization of the Roman symbol served to directly link the regime, and the state, with ancient Rome (Fadda 726).

The choices of interior materials also reveal ideological layers. The marbles throughout the train and ticket hall of Santa Maria Novella Station are not simply the result of aesthetic choice but are explicit references to the Fascist regime and imperial Rome. The ancient Romans prominently clad their buildings’ concrete structures (not concrete as is understood today) with precious marbles (Rifkind 133). Therefore, by mirroring this ancient practice, cladding the interior of the station with various marbles created a tangible visual connection between the Fascist regime and Roman precedents. Given this link to Roman grandeur, the use of marble establishes the station as monumental, in contrast to the exterior design which reduced any suggestion of monumentality (Rifkind 135). Some of the specific marbles include the yellow Siena walls, white Carrara ceiling, and green marble pillars (Rendon).

Moreover, this embrace of ancient materials in the station occurred alongside the prominent integration of modern materials: glass and iron. The glass “waterfall” of Santa Maria Novella Station is one of its most defining features. The waterfall creates a connection between the train hall and exterior. As one follows the waterfall, they are led from the train hall through the ticket hall and finally out of the main entrance, or vice versa. Again, the use of these materials held ideological significance for the regime. Firstly, glass’s prominent role served to communicate the state’s technological advancement. Furthermore, “non-corroding” metals like iron were perceived to have a quality of permanence, a quality the regime similarly wanted to exude (Rifkind 151). Moreover, the direct integration of ancient marbles with 20th century materials directly exemplifies Rationalist and Fascist intentions to “straddle” the Italian past while simultaneously projecting their modernity.

Finally, it is necessary to critically re-examine the site of Santa Maria Novella Station itself. While the explanation of the new station’s site as resulting from the location of its predecessor is logical, this decision cannot be viewed in isolation from the Fascist context. As established previously, the site of Santa Maria Novella Station is historically charged due to its proximity to the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. Given the arguments of Fadda and Ghirardo, the location of the new Santa Maria Novella Station at a juncture of such historical significance in Florence no longer appears solely pragmatic. Rather, the location appears to be a strategic Fascist device to make a claim to its authority, positioning the regime in continuity with a pinnacle work of Renaissance architecture. It is a reminder of the powers that be (Ghirardo 121). To put a spin on Fadda’s words, Mussolini’s Florence “would thus be the” only one “worthy of standing among the vestiges of the” Renaissance city (Fadda 725).

As seen, there are ideological agendas at work behind the architecture of Santa Maria Novella Station. While it is true that its design was intended to integrate harmoniously with Florence’s historic center, it is also true that the station was made use of as a Fascist propagandistic device with symbolic references embedded within its design, materials, and location. But why do Italian Fascist monuments like Santa Maria Novella Station remain standing today?

19. Mussolini at Piazza della Signoria, Florence 1930 (Image: Hibbert).

19. Mussolini at Piazza della Signoria, Florence 1930 (Image: Hibbert).

20. Main doorway Santa Maria Novella Station (Photo by the author).

20. Main doorway Santa Maria Novella Station (Photo by the author).

21. Fasces (Image: Encyclopedia Britannica).

21. Fasces (Image: Encyclopedia Britannica).

22. Green and yellow marbles. Santa Maria Novella Station ticket hall (Photo by the author).

22. Green and yellow marbles. Santa Maria Novella Station ticket hall (Photo by the author).

23. Green and yellow marbles. Santa Maria Novella Station ticket hall (Photo by the author).

23. Green and yellow marbles. Santa Maria Novella Station ticket hall (Photo by the author).

24. Glass and iron "waterfall." Santa Maria Novella Station (Image: Archivo Fondazione Michelucci).

24. Glass and iron "waterfall." Santa Maria Novella Station (Image: Archivo Fondazione Michelucci).

Why Do Fascist Monuments Remain Standing?

There are a multitude of reasons as to why Fascist monuments remain prevalent throughout Italy. The root cause for their survival into the 21st century was the limited response by Allied powers during the reconstruction of Italy following WWII. Scholars and journalists including Hannah Malone, Ruth Ben-Ghiat, and Sylvia Poggioli explain that the implementation of a policy to remove such monuments was not an Allied priority in Italy. This stance starkly contrasts with the response in Germany where a strict denazification policy was implemented and driven by Allied powers (Poggioli). In 1949, legislation in Germany suppressed Nazi symbolism (Ben-Ghiat). Such suppression included the outright ban of the Nazi party as well as the ban of all Nazi symbols in public (BBC). For Nazi buildings that had not been destroyed in the war, like the Berlin Olympic Stadium and Congress Hall of Nuremberg, their symbols were removed, and the buildings were assigned new functions (Sakalis).

26. Berlin Olympic Stadium (Image: Sakalis BBC).

26. Berlin Olympic Stadium (Image: Sakalis BBC).

In Italy, no comparable program was implemented as such initiative was viewed as impractical. The greatest effort the Allies went to was to recommend only the most egregious monuments be destroyed, while the remainder could be covered or moved (Ben-Ghiat). Moreover, the Allies were ambivalent towards Italian Fascist monuments to begin with. They viewed Italians as victims of the Fascist regime – as a people “led astray by a bad man” (Poggioli).

From an economic perspective, the destruction of Fascist structures was not viable given the sheer quantity of monuments and infrastructure constructed by the regime, as is the case of Santa Maria Novella Station (Malone 449). Given Italy’s financial status following the war, deconstructing Fascist built interventions was not a sound economic decision. What finances were available were put towards the reconstruction of the country (Malone 453-454).

The United States, to which the control of Italy was delegated following WWII, also had its own agenda at play: fighting the spread of communism. Italy suddenly found itself subject to the US anti-communist campaign. The goal of the United States was to maintain social stability while preventing communism from taking root in the country (Ben-Ghiat; Ganser 63). To do so, the CIA backed the Italian mafia, right-wing extremists, and remnants of the Fascist party to undermine the electoral success of the widely popular Communist Party. The US supported the establishment of the right-wing Christian Democrat party, which effectively enabled Fascist politicians and bureaucracy to continue into the new governmental system (Ganser 63-64).

From the Italian point of view, these monuments continued to hold political significance throughout the 20th century, especially for the far-right Italian governments that have stemmed from the legacy of the CIA’s backing. Given the carry-over of Fascist politicians and bureaucracy into the Christian Democrat party, there was little incentive from the Italian state’s perspective to censor Fascist symbols. This would carry into the 1990s, with the advent of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement Party which made direct use of these monuments to support their political rise (Ben-Ghiat).

Left-leaning political movements have also made use of the monuments’ persistence. Take the example of the Roma Pride parade in 2016. Posters for the parade made use of the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, or the “Square Colosseum,” whose facade is inscribed with a quote from Mussolini’s proclamation of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia (Malone 457-478; Ben-Ghiat). The building is now the global headquarters of Fendi. The continued political capital of Italian Fascist monuments is therefore a determining factor in their endurance.

27. Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (Image: Sakalis BBC).

27. Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (Image: Sakalis BBC).

Stemming from this political ambivalence, such monuments have become a part of an acclaimed chapter of Italian artistic heritage and therefore marked as key sites for preservation. This period of Italian artistic production, the ventennio, has come to be considered one of the most innovative for Italian architecture. As discussed, Rationalist buildings, which tend to be less overtly Fascist, were detached from their context and discussed from a solely aesthetic perspective (Malone 457).

Here once more, Santa Maria Novella Station can be considered. The station has and continues to be celebrated as a masterpiece of architect Giovanni Michelucci for its formal and aesthetic innovations in merging Rationalism with the historic style of Florence, while its Fascist contexts are omitted (Cianfarani 34; Rendon). This is especially true given that many of the Fascist references, as noted, are not blatantly obvious to the contemporary viewer.

This aesthetic view of Italian Fascist monuments leads to the question: to what extent do these monuments play a role in contemporary Italian memory of the Fascist state?

Memory of Fascist Monuments

Due to the lack of a defascistization policy under Allied reconstruction coupled with the dehistoricization of Fascist monuments by Italian scholars and politicians, Italian Fascist monuments have been effectively lost from Italian collective memory. When prompted on what Italians think about living with these monuments, head of the Italian branch of conservation organization Docomomo, Rosalia Vittorini commented, “Why do you think they think anything at all about it?” (Ben-Ghiat). Vittorini illustrates the general lack of recognition of these monuments in the daily lives of Italians. Furthermore, Hannah Malone frames this phenomenon saying, “the Fascist period is an absent presence in Italy as its memory is alive, but distorted, fragmented and obscured” (Malone 445). While physical traces survive in great numbers, the public memory of Fascism is more or less absent (Malone 446-447).

But to say that the Fascist past in Italy has been simply forgotten is to overlook the complexity of public memory. Afterall, Vittorini’s quote does not imply that Italians have forgotten about Fascist monuments, but rather that they do not acknowledge or think about them. Moreover, the memory of Italian Fascism is varied across the country. While it is outside the bounds of this discussion to attempt to define Italian collective memory of Fascism in its entirety, several cases, Predappio and Bolzano, will be drawn on to briefly outline the variability of memory and reactions to Fascist architectural remnants.

Admittedly, collective memory is a complex term to define. Carol Kidron, working from Paul Connerton and Maurice Halbwachs’ respective work, outlines the term. “The basic premise of…collective memory is that memory extends beyond the realm of the individual mind and its private recollections of the past and may be understood as a perpetually evolving collective social artifact” (Kidron).

Collective memory operates at a group level and continually evolves. Moreover, Collective memory is distinct from “history” as it is “an ongoing, living experience.” History, on the other hand, is detached from the events that are described, with “no direct link between” the viewer and the historic events themselves (Heynen 371-373).

Scholarship on collective memory has also established the role of urban space and architecture as keystones of preserving and “propelling” memory. Halbwachs outlines the dynamic relationship between memory and space,

When a group is introduced into a part of space, it transforms it to its image, but at the same time, it yields and adapts itself to certain material things which resist it. It encloses itself in the framework that it has constructed. The image of the exterior environment and the stable relationships that it maintains with it pass into the realm of the idea it has of itself…The group leaves its traces in space and space is part of the group’s identity.

In other words, the group transforms space while at the same time the space imprints itself on the group. Italian architect Aldo Rossi furthers this idea. He explained that collective memory is “anchored in space” by the monuments and architecture of the city. Certain monuments are “propelling” as they serve key functions in the city. Others are “pathological,” or historical, in that they are no longer functional, yet they remain as important connections to the past (Heynen 372).

With this framework in mind, we can look to case studies of Fascist monuments in Italian cities to better understand how collective memory is at work. Such examples will lay out the diverse and varied memory of Italian Fascism through Fascist monuments. In doing so, the complexity of collective memory, Fascism, and its monuments will be illustrated.

Case Studies: Predappio & Bolzano

Paolo Heywood’s anthropological studies of Predappio, Italy offer a lens into the complexity of Italian memory and acknowledgement of Fascist monuments. Predappio is the birthplace of Benito Mussolini. Locals constantly live in the shadow of Mussolini and are directly confronted with the history of Italian Fascism when walking out their door. As if this was not enough of a reminder, Predappio is also the top site of neo-fascist tourism in Italy, as Mussolini’s body lies there, further aggravating the extraordinary circumstances of life in the town (Heywood 494-495).

To understand the relationship between life in Predappio and its Fascist monuments, one can look to Heywood’s description of Valentina, a 90 year old who has lived her entire life in Predappio, as she walks to the grocery store. Not only does the doorway of her building bear the fasces, but she must also pass the Predappio Casa del Fascio, and finally the site of Mussolini’s birth just meters from the store (Heywood 497-498).

28. Predappio Casa del Fascio (Image: Storchi)

28. Predappio Casa del Fascio (Image: Storchi)

Valentina may know the history of Italian Fascism better than anyone, as she has quite literally lived it. However, she refuses to pay these monuments and symbols any mind. Heywood frames this as a search for “ordinariness.” This is an intentional effort in Predappio (Heywood 495). Of course, residents remember Italian Fascism and are aware of Fascist monuments. However, their extreme circumstances have led them to “live up to an idea of ordinariness” in search of “respite” from the constant confrontation with the legacy of Mussolini’s regime (Heywood 501-503). To do so, residents willfully defy the context in which the acts of their lives occur – framing these acts as ordinary in a most extraordinary place (Heywood 498, 503).

It is necessary to acknowledge that Predappio is perhaps the most extreme case of memory and Italian Fascism. While it cannot be taken as representative of the entire nation, it can offer some understanding into the more general Italian understanding of such monuments. It's not as simple as forgetting. In Predappio, it takes the form of defying these monuments any attention. In Bolzano, Fascist monuments have been dealt with more actively, to neutralize their meanings while acknowledging their history.

Bolzano is a city in the Italian region of South Tyrol. The region was annexed from the Austro-Hungarian Empire following World War I. Mussolini implemented an "Italianization" campaign in the region to increase the Italian population and suppress German speakers’ ability to speak their indigenous language (Marchetti).

Bolzano’s Fascist monuments include the Victory Monument and Bas Relief on Bolzano's finance building. The Victory Monument, built to celebrate Italian “victory” over South Tyrol, embeds explicit Fascist symbols. These specifically include fasces protruding from the columns and an inscription, "Here at the border of the fatherland set down the banner. From this point on we educated the others with language, law, and culture" (Sakalis BBC).

29. Bolzano, Old Town (Photo by the author).

29. Bolzano, Old Town (Photo by the author).

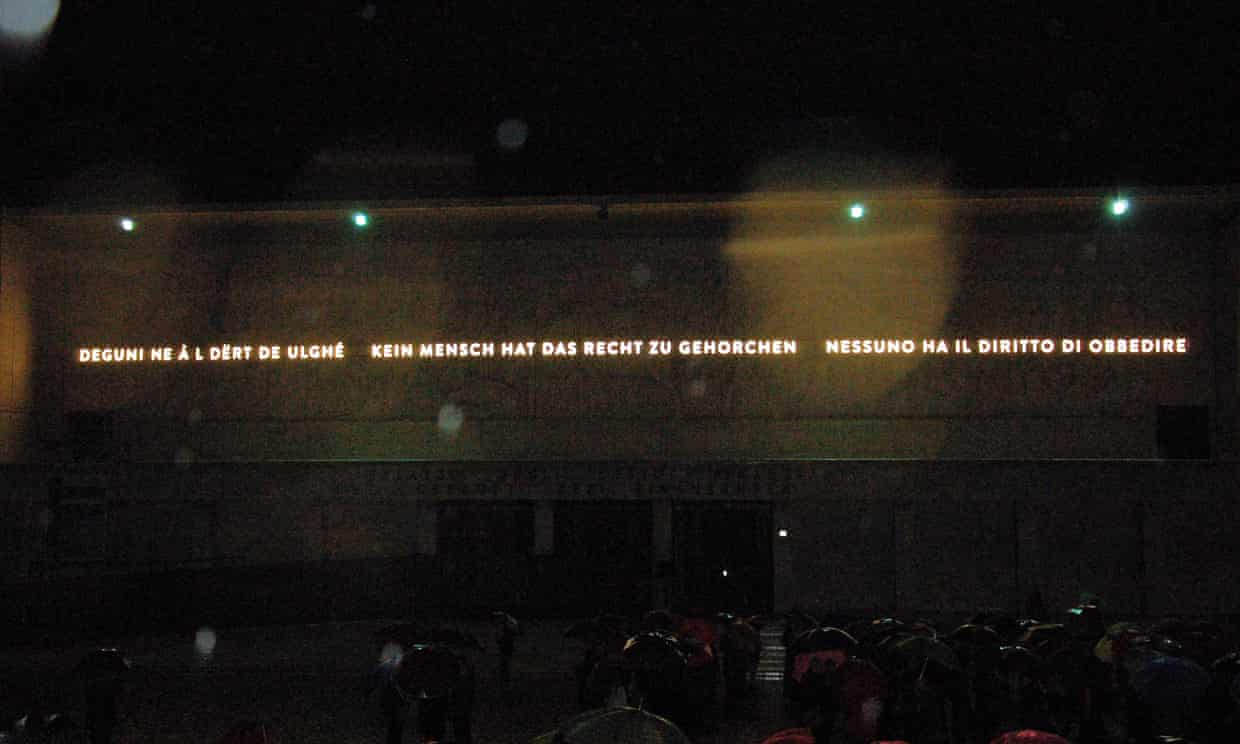

The Bas Relief depicts Mussolini on horseback amidst conquest. It also bears the inscription, “Credere, Obbedire, Combattere” (“Believe, Obey, Combat”) (Invernizzi-Accetti). The monuments remained a source of tension between Bolzano's German and Italian-speakers due to their explicit Fascist messages and references to the colonization and "Italianization" of South Tyrol (Invernizzi-Accetti; Williams).

In 2014, rather than choosing to conserve, ignore, or destroy the monuments, the city implemented light installations to directly respond to the Fascist messages, "neutralizing" them (Invernizzi-Accetti; Sakalis; Williams). For example, a light installation was installed on the Bas Relief to directly respond to its inscription with the message, “Nobody has the right to obey,” in the local languages of Italian, German, and Ladin (Invernizzi-Accetti; Sakalis).

30. Bas relief installation, Bolzano Finance Building (Image: Città di Bolzano).

30. Bas relief installation, Bolzano Finance Building (Image: Città di Bolzano).

The Victory Monument was similarly addressed with a light installation: an LED ring around one of its columns. The ring bears the uniting phrase, “BZ 18 to 45. One monument, one city, two dictatorships.” A museum of fascism in Bolzano was also built beneath the monument (Sakalis; Williams).

31. Bolzano Victory Monument (Image: CBC).

31. Bolzano Victory Monument (Image: CBC).

Such interventions served to unite Bolzano’s ethnic groups and promote democratic values. Bolzano was able to maintain the monuments’ artistic heritage, emphasize their historic significance, respond to their original messages, and defuse tensions between its divided populations (Williams). Bolzano demonstrates the nuance of Italian responses to Fascist monuments and offers a model for how to effectively defascistize such remnants in Italian urban centers (Sakalis). With the ideas of Italian memory discussed, a final question is opened: How can Santa Maria Novella Station’s Fascist links be more actively acknowledged by locals and visitors alike?

Actively Acknowledging Santa Maria Novella Station’s Fascist History

The legacy of Fascist urban interventions remains at play at Santa Maria Novella Station. Visitors continue to walk across the marble floors, following the waterfall through the station with no understanding of their ideological significance. This is little fault of their own as no effort to educate and engage them has been made. This discussion has attempted to recall the decontextualized Fascist architectural elements embedded in Santa Maria Novella Station. Through an in-depth explanation of these elements, the station has been resituated in its Fascist context. A brief outline of why Fascist monuments endure in the 21st century has been established to explain their relationship with contemporary Italian memory.

But how can such monuments be more actively acknowledged and remembered? To foster thinking about memory and the role of memorials, we can look to two architectural theorists who have worked on public memory in public spaces: Julian Bonder and Hilde Heynen. Bonder’s text “On Memory, Trauma, Public Space, Monuments, and Memorials,” grapples with how a memorial ought to function. Bonder also evaluates the position of the visitor in this engagement. Bonder’s main contention is that memorials should simultaneously bridge the past, present, and future. Moreover, they should actively encourage a “critical consciousness” in the viewer’s process of reflection. Monuments can act as a warning for the future while also helping to envision “a better world” (Bonder 62).

Hilde Heynen’s text, “Petrifying Memories: Architecture and the Construction of Identity,” explores the relationship between urban space and memory. Heynen draws on the example of the Basilica of the Sacré Coeur on the hill of Montmartre in Paris to illustrate how memory is embedded in urban spaces. The hill was the site of a popular uprising in the 1870s. The catholic church’s decision to construct a basilica that would symbolically sit over Paris was considered a provocation towards this movement’s history.

Today, as tourists flock to the Basilica, they remain unaware of the contested origins of the church, similar to the unawareness of travelers to Santa Maria Novella Station’s Fascist origins (Heynen 373).

Heynen proposes the opportunity, given that cities and architecture are sites of memory, to create a “kaleidoscopic” image of history, with overlapping layers of truths (Heynen 375). Moreover, Heynen contends that the “power” embedded in urban spaces be harnessed “to provide records of public history, which would be more evenly distributed in terms of class, race and gender. Public history would thus become richer, culturally more diverse, and less dominated by the white, middle-class and male viewpoint” (Heynen 375).

The ultimate question is how can Santa Maria Novella Station’s Fascist history and architectural references be acknowledged and engaged with today? While this question is about memory, it also comes at a time of urgency in Italian politics. Although Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni denies any connection, her links to Italian Fascism are well documented. Firstly, she is the leader of the Brothers of Italy party, which has stemmed from Mussolini’s Fascist party. Moreover, her slogan, “God, Homeland, Family,” appropriated from Mussolini, continues this alignment with his fascist party (Saviano; D’Emilio). The point here is not to suggest that Meloni’s government signals the return of Mussolini’s regime. However, there is an underlying risk associated with an Italian neo-fascist government as it pertains to Fascist monuments. As Ruth Ben-Ghiat points out, “In Italy, where they never went away, the risk is different: if monuments are treated merely as depoliticized aesthetic objects, then the far right can harness the ugly ideology while everyone else becomes inured” (Ben-Ghiat). Right-wing or Fascist Italian political parties may harness these monuments as political instruments. Therefore, there is an urgency to take action to neutralize, respond to, and engage with these monuments’ histories. Santa Maria Novella Station is no exception, as millions will continue to arrive to Florence through its doors for the foreseeable future.

About the Author

Finn Love is a senior undergraduate at Binghamton University in New York studying art history, environmental planning, and global studies. Finn studied abroad in Florence, Italy in the fall of 2023. This piece is a culmination of his time abroad and studies of urban planning and art history. Finn hopes to return to Italy very soon to continue his research of Italian modern architecture, ride the high speed train, and have some proper espresso.

Fotoautomatica of the author (right) and his uncle in Florence, 2023 (Photo by the author).

Fotoautomatica of the author (right) and his uncle in Florence, 2023 (Photo by the author).

Bibliography

Andreotti, Libero. “Michelucci, Giovanni.” The Dictionary of Art. 1996.

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. “Why Are So Many Fascist Monuments Still Standing in Italy?” The New Yorker, 5 Oct. 2017. www.newyorker.com, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/why-are-so-many-fascist-monuments-still-standing-in-italy.

Bonder, Julian. “On Memory, Trauma, Public Space, Monuments, and Memorials.” Places, vol. 21, no. 1, May 2009. escholarship.org, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4g8812kv.

Cianfarani, Francesco. “The Fascist Legacy in the Built Environment.” The Routledge Companion to Italian Fascist Architecture, Routledge, 2020.

Cisternino, Alfredo. “Lecture 4: Le Corbusier.” Presentation, 20th Century Design and Architecture Lorenzo de Medici Institute, Florence, Italy, October 11, 2023.

Davies, Paul, and David Hemsoll. “Alberti, Leon Battista.” Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 26 May 2010, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000001530.

D’Emilio, Frances. “Far-Right Leader Giorgia Meloni Installed as Italy’s Premier.” Associated Press, 22 Oct. 2022, https://apnews.com/article/silvio-berlusconi-matteo-salvini-giorgia-meloni-italy-europe-81b662bb7a62184968b1567564b3287f.

Fadda, Salvatore. “The Refiguring of Ancient Rome in Fascist Italy’s National Imagination.” Nations and Nationalism, vol. 27, no. 3, 2021, pp. 721–33. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12651.

“Fascist Movement, Italy.” Oxford Reference, https://doi.org/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095811424. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

FS Italiane. “Florence Santa Maria Novella Station.” FS Italiane, https://www.fsitaliane.it/content/fsitaliane/en/innovation/transport-technology/main-hs-stations/florence-santa-maria-novella-station.html. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023.

Ganser, Daniele. NATO’s Secret Armies: Operation GLADIO and Terrorism in Western Europe. Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

Ghirardo, Diane Yvonne. “Italian Architects and Fascist Politics: An Evaluation of the Rationalist’s Role in Regime Building.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 39, no. 2, 1980, pp. 109–27. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/989580.

Heynen, Hilde. “Petrifying Memories: Architecture and the Construction of Identity.” Journal of Architecture, vol. 4, no. 4, Jan. 1999, pp. 369–90. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/136023699373765.

Heywood, Paolo. “Out of the Ordinary: Everyday Life and the ‘Carnival of Mussolini.’” American Anthropologist, vol. 125, no. 3, 2023, pp. 493–504. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13850.

Hibbert, Christopher. Florence: The Biography of a City. 1st American ed., W.W. Norton & Co., 1993.

Invernizzi-Accetti, Carlo. “A Small Italian Town Can Teach the World How to Defuse Controversial Monuments.” The Guardian, 6 Dec. 2017. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/06/bolzano-italian-town-defuse-controversial-monuments.

Kallis, Aristotle. “‘Framing’ Romanità: The Celebrations for the Bimillenario Augusteo and the Augusteo–Ara Pacis Project.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 46.4, 2011, pp. 809–31, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009411413407.

Kidron, Carol A. “Memory.” Oxford Bibliographhy, 28 Nov. 2016, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0155.xml.

Larkin, Brian. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 42, no. 1, 2013, pp. 327–43. Annual Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

Malone, Hannah. “Legacies of Fascism: Architecture, Heritage and Memory in Contemporary Italy.” Modern Italy, vol. 22, no. 4, Nov. 2017, pp. 445–70. Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/mit.2017.51.

Marchetti, Silvia. “The South Tyrol Identity Crisis: To Live in Italy, but Feel Austrian.” The Guardian, 30 May 2014. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/may/30/south-tyrol-live-in-italy-feel-austrian.

Meeks, Carroll L.V. The Railroad Station: An Architectural History. Mineola, Dover Publications, 1995.

Poggioli, Sylvia. “Italy Has Kept Its Fascist Monuments and Buildings. The Reasons Are Complex.” NPR, 25 Feb. 2023. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2023/02/25/1154783024/italy-monuments-fascist-architecture.

Rendon, Alice. “Italian Rationalism with Giovanni Michelucci and the ‘Tuscan Group’ Brutalism with Leonardo Savioli.” Presentation, The Built Environment of Florence Lorenzo de Medici Institute, Florence, Italy, November 30, 2023.

Rifkind, David. “The Radical Politics of Marble in Fascist Italy.” Radical Marble, Routledge, 2018.

Sakalis, Alex. “What Happens to Fascist Architecture after Fascism?” BBC, 17 Jan. 2022, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220117-what-happens-to-fascist-architecture-after-fascism.

Saviano, Roberto. “Giorgia Meloni Is a Danger to Italy and the Rest of Europe.” The Guardian, 24 Sept. 2022. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2022/sep/24/giorgia-meloni-is-a-danger-to-italy-and-the-rest-of-europe-far-right.

Simons, Baya. “The Stories behind the World’s Great Train Stations.” The Financial Times Limited | London, Apr. 2023. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2798963263/citation/E58C9286B1946AAPQ/1.

Ward, William. “Rationalism: Architecture in Italy Between the Wars.” The Thirties Society Journal, no. 6, 1987, pp. 32–41.

Watkin, David. A History of Western Architecture. London, Laurence King, 2015.

Williams, Megan. “How This Italian City Worked to ‘neutralize’ Its Controversial Fascist-Era Monument | CBC News.” CBC, 29 Oct. 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/bolzano-italy-victory-monument-lessons-1.6632883.

Mediography

1. Love, F. (2023). View of Santa Maria Novella Station, Florence [Photograph].

2. Michelucci, G. (1933-34). Cantiere [Photograph]. Stazione di Santa Maria Novella, Firenze 1932-1935. http://db.michelucci.it/archivi/fotografie/?opera=P039.

3. Love, F. (2023). Frecciarossa high speed train arriving at Santa Maria Novella Station [Video].

4. Love, F. (2023). Santa Maria Novella Station [Video].

5. Love, F. (2023). Basilica of Santa Maria Novella Station, Florence [Photograph].

6. Città Metropolitana di Firenze. (2020). [Fortezza da Basso] [Photograph]. Città Metropolitana di Firenze. https://www.cittametropolitana.fi.it/fortezza-da-basso-via-ai-lavori-di-ristrutturazione/.

7. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (2007). “Historic Centre of Florence [Map]. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/174/.

8. Love, F. (2023). View of Piazza Santa Maria Novella [Video].

9. [Photographer Unknown]. [Interior of Santa Maria Novella Station] [Photograph]. Meeks, Carroll L.V. The Railroad Station: An Architectural History. Mineola, Dover Publications, 1995.

10. Mazzoni, A. (1932) [Santa Maria Novella Station initial design proposal by Angiolo Mazzoni] [Drawing]. Rendon, Alice. “Italian Rationalism with Giovanni Michelucci and the ‘Tuscan Group’ Brutalism with Leonardo Savioli.”

11. Nodo libri Como. Principal Front [Photograph]. https://architectuul.com/architecture/casa-del-fascio.

12. Michelucci, G. (1932) Vista prospettica dell'esterno [Drawing]. Stazione di Santa Maria Novella, Firenze 1932-1935. http://db.michelucci.it/archivi/fotografie/?opera=P039.

13. Bazzechi, I. (1960s). Veduta a volo d'uccello [Photograph]. Stazione di Santa Maria Novella, Firenze 1932-1935. http://db.michelucci.it/archivi/fotografie/?opera=P039.

14. Love, F. (2023). View of Santa Maria Novella Station, Florence [Photograph].

15. Love, F. (2023). View of Santa Maria Novella Station, Florence [Photograph].

16. Kossel, E. (2022). Stazione Santa Maria Novella, Florenz, Detail der Hauptfassade [Photograph]. “Das »Haus aus Glas« und sein langer Schatten: Moderne und Staatsrepräsentation während des italienischen Faschismus und im ›Dritten Reich‹.” https://doi.org/10.1515/atc-2019-2004.

17. Kossel, E. (2022). San Lorenzo, Florenz, Detail des non finito der Hauptfassade [Photograph]. “Das »Haus aus Glas« und sein langer Schatten: Moderne und Staatsrepräsentation während des italienischen Faschismus und im ›Dritten Reich‹.” https://doi.org/10.1515/atc-2019-2004.

18. Places of Fascism. (2024). [Database map of Florence] [Screen Capture]. Places of Fascism. luoghifascismo.it.

19. [Photographer Unknown]. (1930). [Mussolini at Piazza della Signoria, Florence] [Photograph]. Hibbert, Christopher. Florence: The Biography of a City. 1st American ed., W.W. Norton & Co., 1993.

20. Love, F. (2023). Main doorway Santa Maria Novella Station [Photograph].

21. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. (2011). Fasces. [Image]. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/fasces.

22. Love, F. (2023). Green and yellow marbles. Santa Maria Novella Station ticket hall [Photograph].

23. Love, F. (2023). Green and yellow marbles. Santa Maria Novella Station ticket hall [Photograph].

24. Fondazione Michelucci Giovanni. (1990s). Dettaglio della vetrata dall'interno [Photograph]. Stazione di Santa Maria Novella, Firenze 1932-1935. http://db.michelucci.it/archivi/fotografie/?opera=P039.

25. Love, F. (2023). Train hall of Santa Maria Novella Station today [Photograph].

26. Serena Gilmour, Angela. (2010). Olympic Stadium, Berlin, Germany [Photograph]. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220117-what-happens-to-fascist-architecture-after-fascism.

27. Messana, Marie-Laure. (2014). [The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana] [Photograph]. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220117-what-happens-to-fascist-architecture-after-fascism.

28. Storchi, Simona. (2019). The ex Casa del Fascio in Predappio [Photograph]. Modern Italy. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/mit.2019.8.

29. Love, F. (2023). Bolzano, Old Town [Photograph].

30. Città di Bolzano. [Bolzano Bas Relief Light Installation] [Photograph]. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/06/bolzano-italian-town-defuse-controversial-monuments.

31. Williams, Megan. (2022). [The Monument to Victory Bolzano, Italy] [Photograph]. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/bolzano-italy-victory-monument-lessons-1.6632883.

32. Michelucci, G. (1932) Vista prospettica dell'esterno [Drawing]. Stazione di Santa Maria Novella, Firenze 1932-1935. http://db.michelucci.it/archivi/fotografie/?opera=P039.