Maternity Leave

The Falling Birth Rates in Italy and Social Policy Reform

Introduction

Maternity leave is the essential period both during and after pregnancy in which new mothers are allowed the time to recuperate from the taxing process of childbirth and facilitate a bond with their newborn. Most countries across the globe have policies established that guarantee some form of parental leave, albeit variable from country to country in terms of duration and monetary compensation. However, with the extremely low birth rates in Italy, it is important to investigate what barriers may be in place that are preventing or discouraging Italian women from having children and what changes can be made to further provide support to new parents.

During my time abroad in Italy, I was surprised by how common it was to see graffiti lining the streets of Florence. On every street corner, I couldn't help but notice new pieces of art and I began to keep a collection of the graffiti pieces I came across. In doing so, I found several artworks centered around certain feminist ideologies -- such as bodily autonomy and gender equality. The graffiti style seen along the streets of Italy is very different in style compared to the traditional “tagging” graffiti that is commonly seen in America. Among the streets of Italy, graffiti seems to hold a more personal and artistic take, with many pieces containing political messages or phrases of empowerment. Located on a small sidestreet by the Torre della Castagna, I was immediately drawn to a graffiti piece that states "SMASH THE PATRIARCHY".

A piece of graffiti located in Florence, with the words "Smash the Patriarchy" (photo by me).

A piece of graffiti located in Florence, with the words "Smash the Patriarchy" (photo by me).

I found another piece located near the Mercato del Porcellino, the heart of the historic center, stating "BANS OFF MY BODY".

A piece of graffiti located near the Mercato del Porcellino in Florence, stating "Bans Off My Body" (photo by me).

A piece of graffiti located near the Mercato del Porcellino in Florence, stating "Bans Off My Body" (photo by me).

Seeing these graffiti pieces made me wonder what current social issues may be on the rise to warrant such a response through public artwork such as graffiti. Later research on inequalities in Italy led me to the crisis surrounding the falling birth rate, where the number of deaths in Italy now outweighs the number of births. More now than ever, women in Italy are made to choose between pursuing a family or a career, due to difficulties in maintaining a stable job, limited childcare, and the cost of child-rearing. It is evident that the current legal provisions provided during the maternity period are not sufficient to provide adequate levels of support to new parents.

The transition to parenthood has often been identified as a crucial life event, as it encompasses many psychological, neurobiological, and socio-relational adjustments. The role of paid maternity leave is imperative for creating a support system for new mothers, as it provides time away from their careers to recuperate from the physical stress of birth, time to care for their child, and ensures that their career will still be in place afterward. This project aims to highlight the importance of providing adequate maternity leave policies and to investigate what barriers may be in place for Italian women that make childbearing and parental leave more difficult.

The Genealogy of Maternity Leave

The introduction of maternity leave across the globe can be traced back to the growing involvement of women in the workforce during the early 20th century. Prior to Industrialization, women's work was rarely recorded or recognized, as a majority of working mothers in Europe were participating in home-based work or agricultural work (Son 2023). During the First World War, women's participation in the labor market soared as there was a large demand for workers. Women began to replace men within sectors that were previously male-dominated, working on building tanks, filling shells, and meeting other demands on the homefront for the war effort. For this reason, the war has often been cited as one of the primary factors for the feminization of employment (Gardey, Maruani, and Meron 2022).

Young Italian women who were recruited by the British Army to unload artillery ammunition for the war (Bartoloni 2015).

Young Italian women who were recruited by the British Army to unload artillery ammunition for the war (Bartoloni 2015).

This period called for the end of the ideology of “separate spheres” – the concept that men and women held different domains, with the women's domain being within the home. After the war, feminist groups began to try and fight for special protections and equal treatment. With the demand for female labor ever on the rise, it became clear that a balance between productive and reproductive labor was necessary. Productive labor is a type of labor that results in the production of goods and services which hold a monetary value within a capitalist system, and therefore result in compensation through wages. Reproductive labor is any type of labor that an individual has to do for themselves, that is not for the purpose of receiving a paid wage, including tasks like cooking, cleaning, or child-rearing (Shaw and Lee 2007).

In 1919, the International Labor Organization (I.L.O.) was created, and the primary item on the list for their first conference was maternity leave protections, calling for provisions that provided paid leave, break times for breastfeeding, and job protection for those on leave. Before this first meeting of the I.L.O., most nations in Europe only called for three to four weeks of unpaid leave, which created a difficult situation for families of low economic status. At this meeting, the Labor Commission created a group of voting delegates that was entirely made up of men, only calling on women to serve as nonvoting “advisors” for issues that they believed specifically affected women. Feminist groups and female trade unionists banded together and marched upon the conference, arguing for a standard 12 weeks of leave to be established as both a medical necessity and a social right (Seigel 2019). This fight continued until the final day of the conference, in which the Maternity Protection Convention of 1919 was passed, creating an international standard for 12 weeks of paid maternity leave. At the time of its passing, not a single nation in the world met the standard passed by the I.L.O.. However, over time, nations began to advance their policies, with many going well over the I.L.O. standard of 12 weeks. For example, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental organization focused on the development of policies that promote economic growth, noted the average for paid leave had reached 51 weeks in the year 2022, with countries like Finland providing over a year's worth of leave (OECD Family Database N.d.).

Maternity Leave in the United States

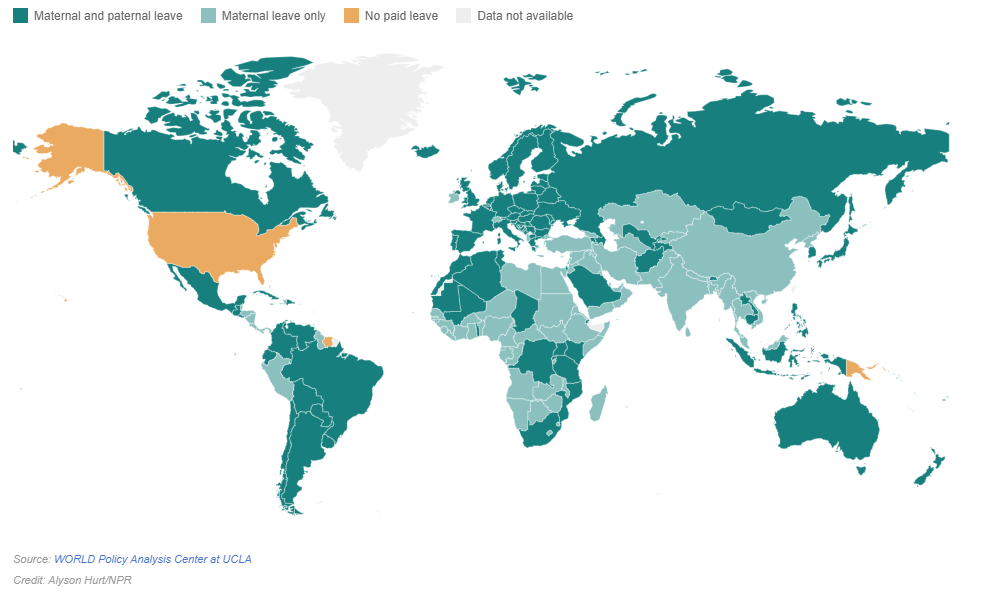

As previously discussed, paid maternity and parental leave allows parents with newborns to meet their personal and familial needs without the worry of job security or loss of financial support. However, the United States severely lags behind other developed countries regarding the length and benefits of their parental leave policies, as there is currently no federal policy that guarantees paid leave. In 1919, with the meeting of the first International Labour Conference, countries from across the globe came together to establish the very first gender equality international labor standard. At this conference, the United States was one of the few participating nations to not ratify the document, instead creating its own set of policies – which have been described as “half-hearted” and “characterized by strong racial preferences” (Seigel 2019). As of 2018, almost 100 years following the original International Labour Conference, 33 of the 34 member nations of the OECD guaranteed paid parental leave in some capacity. The United States was not one of them. Below is a global map showing the current parental leave policies in different countries (Deahl 2016). The United States is one of eight countries, and the only high-income country – as defined by the World Bank – to not provide a paid maternity leave.

The extent of parental leave provisions across the globe (Deahl 2016).

The extent of parental leave provisions across the globe (Deahl 2016).

It was not until 1993 that the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) was passed, which provided up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to eligible employees for specified family and medical reasons, including childbirth. To be eligible for FMLA, the employee must have been employed for at least 12 months and completed at least 1,250 hours of service for their current employer within that period (The Federal Register 1993; Vezzosi 2007). Additionally, the FMLA only applies to individuals who work for an employer or worksite that employs more than 50 people within a 75-mile radius. According to the Federal Register, the goal of this policy is to increase productivity within the workplace by providing a working environment where employees can have a better balance between work and family. While this is unquestionably a step in the right direction, the extent of this policy is incredibly narrow and does not provide the proper protections to provide genuine support or to see legitimate results. Not only is the leave provided by the FMLA unpaid, but the eligibility requirements create a limited scope of reach, resulting in a severe lack of support for mothers in this country. Additionally, due to the lack of federal protections guaranteeing paid leave, there are large disparities in the experiences women have across the country, varying by demographic, state of residency, and company of employment. As a citizen of this country, it is appalling that the United States has continually refused to advance its policies and many others share the same sentiment.

A thread on the social media app 'Reddit' shares some commentary from individuals across the globe on how their country handles maternity leave, as well as several comments discussing the failures in US policies.

Reddit is a social media forum that allows users to ask questions and create discussions with hundreds of users across the globe. The original thread was posted to the subreddit r/AskEurope in November of 2022 and asked, "How does maternity/paternity leave in your country work?", prompting users to share their personal experiences. With over a hundred responses, users from around the world shared the policies in their country as well as their personal experiences and grievances ([Accomplished_Hyena_6] 2002).

One user from the United States, [JD-800], shared a story about a family member's experience with maternity leave, describing how they did not qualify for FMLA and had no choice but to go back to work just two short weeks after giving birth. Part of this decision was rooted in fear of disciplinary action from their employer, as well as a need for monetary income to support themselves and their new baby. The user stated "It's always fun to read the posts on this sub-Reddit because I literally can't imagine there are places with some of the policies that you all mention. Feels like I'm reading about a fantasy land" (JD-800 2022).

In response to the post by [JD-800], users gathered together to express their shock and disbelief. A user from Germany [El_Grappadura] commented on the thread, outraged after hearing about the experiences of people in the United States. "To me it is always surprising to read the s*** Americans are putting up with. I am always wondering why you guys are not out on the street protesting every single day... the whole system is so screwed up, I really pity you (El_Grappadura 2022).

It is important to take into account the experiences of these individuals as it is a firsthand account of the different parental leave policies currently in place for different countries. A discussion thread such as the one that the Reddit forum provides allows individuals to highlight the benefits of their current policies and point out which methods are inefficient. To many, it is a shock that the United States still will not guarantee a form of paid leave to those experiencing the transition to parenthood. Many Americans tend to stress the idea of individualism and laissez-faire, not wanting the government to get involved in such affairs. As such, they tend to view maternity leave as a privilege rather than a right that should be guaranteed by the government, making it difficult to provide federal support to those who need it.

Maternity Leave in Italy

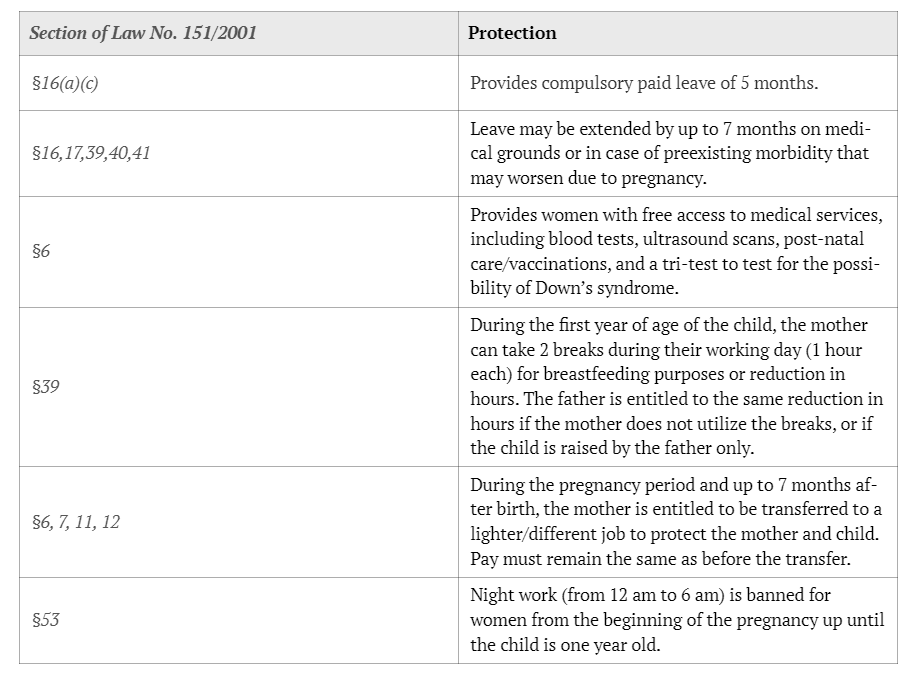

Like many of its European counterparts, Italy has a much more extensive parental leave policy in place for new parents. There are several provisions from previous cases and laws that have been consolidated into one approved law – Law No. 151/2001 – which dictates all the following protections. New mothers are guaranteed up to 5 months of paid maternity leave, which is typically paid in part by the National Institute for Social Security (INPS) (Employment, Social Affairs, and Inclusion n.d.). During this leave, the mother is entitled to 80% of their regular pay from the INPS, and the other 20% is paid by the employer such that the worker receives 100% of their normal salary. Typically women will take 2 months off before the birth and 3 months following the birth, but the planning for leave is very flexible and will vary by individual. One great component of this policy is that there are no specific provisions in place that limit eligibility for maternity leave – ALL pregnant employees are eligible for leave, regardless of duration of employment. There are also protections in place that prevent employees from being fired from their jobs from the beginning of the pregnancy, up until one year after the child's birth. Italy also provides paternity leave, providing fathers with 10 days of compulsory paid leave. Below is a chart highlighting some of the main provisions provided by Law No. 151/2001.

Table describing some of the current protections guaranteed by Law No. 152/2001 (Gnot 2011).

Table describing some of the current protections guaranteed by Law No. 152/2001 (Gnot 2011).

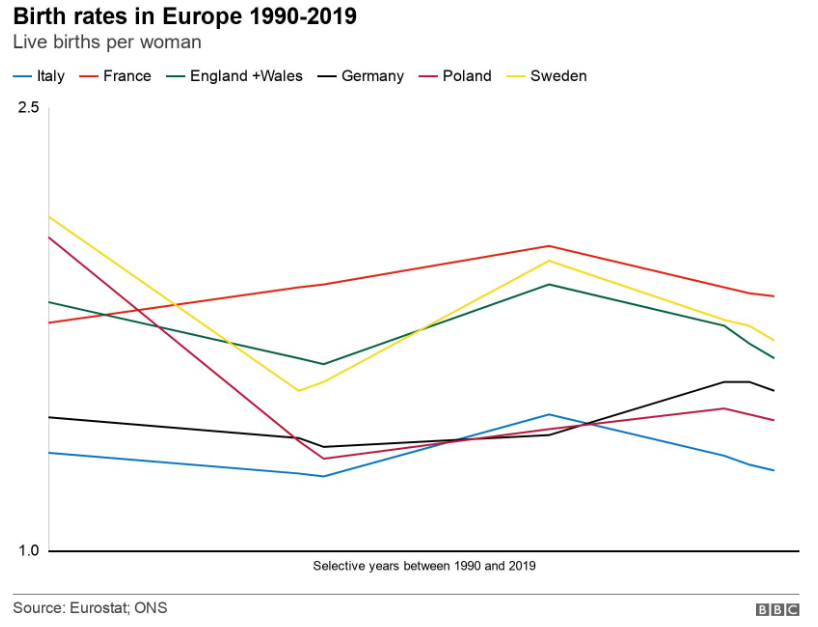

Yet despite the provisions set in place by Law No. 151/2001, the birth rate in Italy is falling to a concerningly low number which places the country in a state of crisis. The number of births has now fallen below 400,000 per year, which according to the Italian National Institute of Statistics, is the lowest since it began in 1861 and the lowest in the European Union (EU) (Nadeau et al. 2023). The number of deaths in Italy now exceeds the number of births, placing its replacement rate in the negatives – 12 deaths for every 7 births. This creates a major predicament for the southern European country, especially regarding its pension system, which is already being spread thin. Most of the concern is centered around the idea that fewer births would mean fewer people entering the workforce, even as more people retire. As Italy has a “pay-as-you-go” pension system, where its current workers pay for the pension benefits of older retired workers, this could create a huge burden on the system. By the year 2030, over 2 million people will enter retirement with no new members of the workforce to pay their pensions (Nadeau et al 2023).

Graph showing the changes in birth rates in Europe from the years 1990 to 2019 (Lowen 2021).

Graph showing the changes in birth rates in Europe from the years 1990 to 2019 (Lowen 2021).

If the maternity leave policies in Italy are so much more progressive than in the United States, then why is the birth rate so low? Even with 5 months of paid parental leave, many mothers in Italy are still finding it difficult to have children due to other financial, psychosocial, and vocational barriers. Italy may be miles ahead of the United States in terms of the implementation of paid maternity leave, but they still have a myriad of policy changes that could be utilized to better the experiences of new mothers and alleviate some of the burdens that new parents face in their transition to parenthood.

Job Security

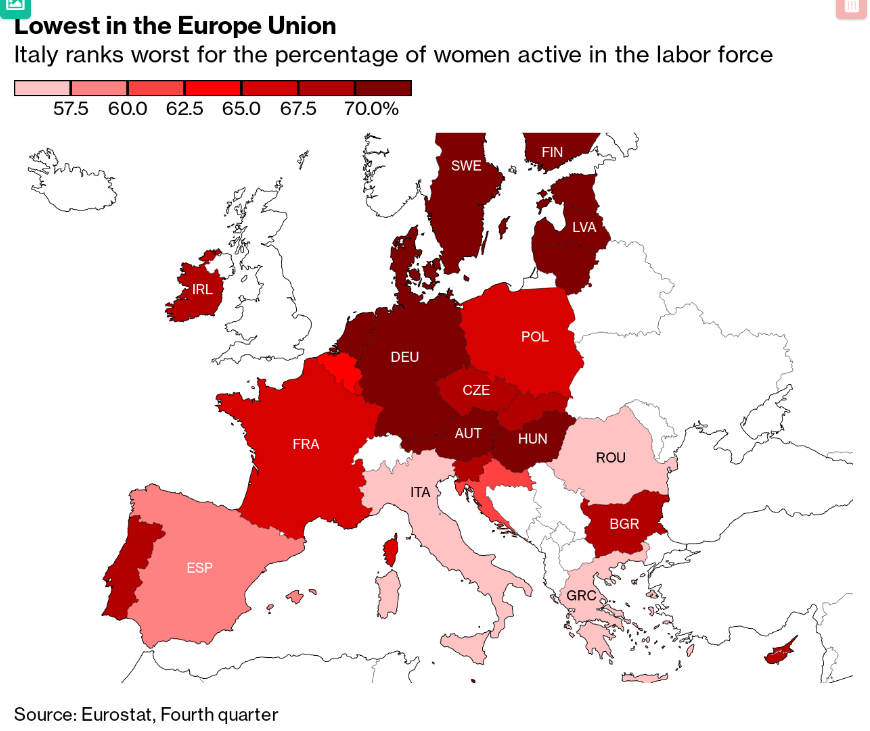

Despite hitting a record high of 52%, Italy still has the lowest female employment rate in the EU, almost 14 points lower than the average, further contributing to issues regarding economic growth (Za, Fonte, and Anzolin 2023). Not only would closing the gap in female employment boost the workforce and GDP by 10%, but research has shown that women in richer economies are more likely to have children if they work (Za, Fonte, and Anzolin 2023; Doepke et al. 2022).

Percentage of women active in the labor force across the European Union (Salzano 2023).

Percentage of women active in the labor force across the European Union (Salzano 2023).

Despite the current provisions of Law No. 151/2001, women still feel as if they must choose between their career and their family. A survey by the National Institute for Analysis of Public Policies (INAPP) found that over half of the female participants in Italy said that they found it impossible to combine work and childcare simultaneously, with nearly one in five women under the age of 50 leaving their job after giving birth to their first child (Za, Fonte, and Anzolin 2023; INAPP News 2023). Beyond that, Italian women have faced a history of discrimination in the workplace from employers who refuse to respect their maternity rights because of cultural views that place the primary role of women within the home. Oftentimes, being a mother or even being of childbearing age allows for the justification of lower wages and limited job security (Mills 2003).

One of these is called “white resignations”, in which an employer forces new female workers to sign undated resignation letters that can later be used against them if they were to become pregnant or face a long-term illness or disability (Hornby 2012). So although there are legalized protections for pregnant women in Italy, those protections are not always realized. In a society where securing a stable job is already a difficult endeavor, many young Italian women are forced to decide between having children and continuing their careers.

Childcare Availability

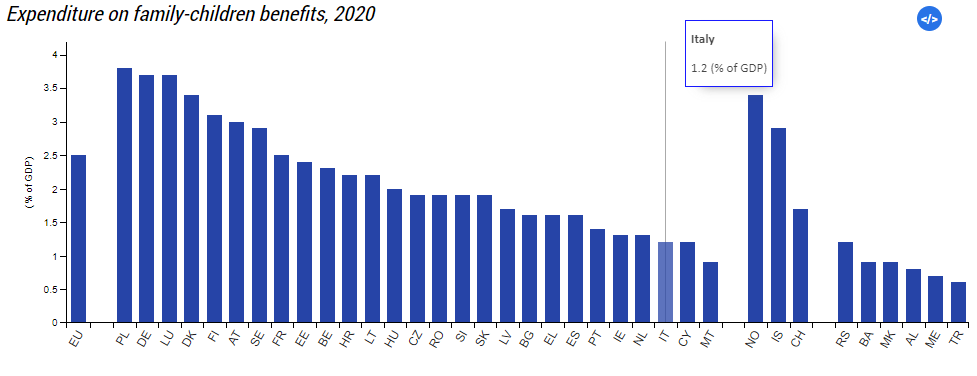

Another predicament that contributes to the delay in family-making revolves around the limited childcare services available for young children. Currently, Italy provides 26.6 nursery spots for every 100 children under the age of three. This is well below the goal of 33 per 100 children that was set by the EU’s Barcelona agenda that discussed women's rights (Za, Fonte, and Anzolin 2023). A young mother from Turin, Italy shared her experience with finding an available nursery for her 6-month-old baby, expressing her frustration and panic of not being able to find childcare by the time she reached the end of her maternity leave. She stated, “After a lifetime of sacrifices, studies, and commitment, every time I hear talk of gender equality a shiver runs down my spine and I think of the opportunities I will miss, the limits and slowdowns that my professional life will suffer; and I ask myself: If I had a daughter, what example could I have set for her?” (Santacroce 2023). Women should not feel as if they must choose between different aspects of their lives – family, career, hobbies – when adequate social support can make it possible to do so much more. In Italy, only 1.2% of the total GDP is dedicated to family-child benefits, comparatively lower than the EU average of 2.5%. Additionally, Italy only spends 0.1% of its GDP on childcare services for children under the age of 3, much lower compared to countries like France and Denmark, which spend 0.6% and 0.8% respectively (Za, Fonte, and Anzolin 2023).

The percent of GDP spent on family-children benefits across the globe in 2020, as well as the EU average (Eurostat 2023).

The percent of GDP spent on family-children benefits across the globe in 2020, as well as the EU average (Eurostat 2023).

Health of the Mother

From a neurobiological standpoint, there are many reasons that we should be providing adequate social support for new mothers, as it can be protective of the mother's physical and mental health. The act of childbirth takes a huge toll on the bearer of the child and can lead to many complications that affect the physical health of the mother. As such, it is best practice to ensure that an acceptable amount of time is given to new parents for both physical and mental recovery.

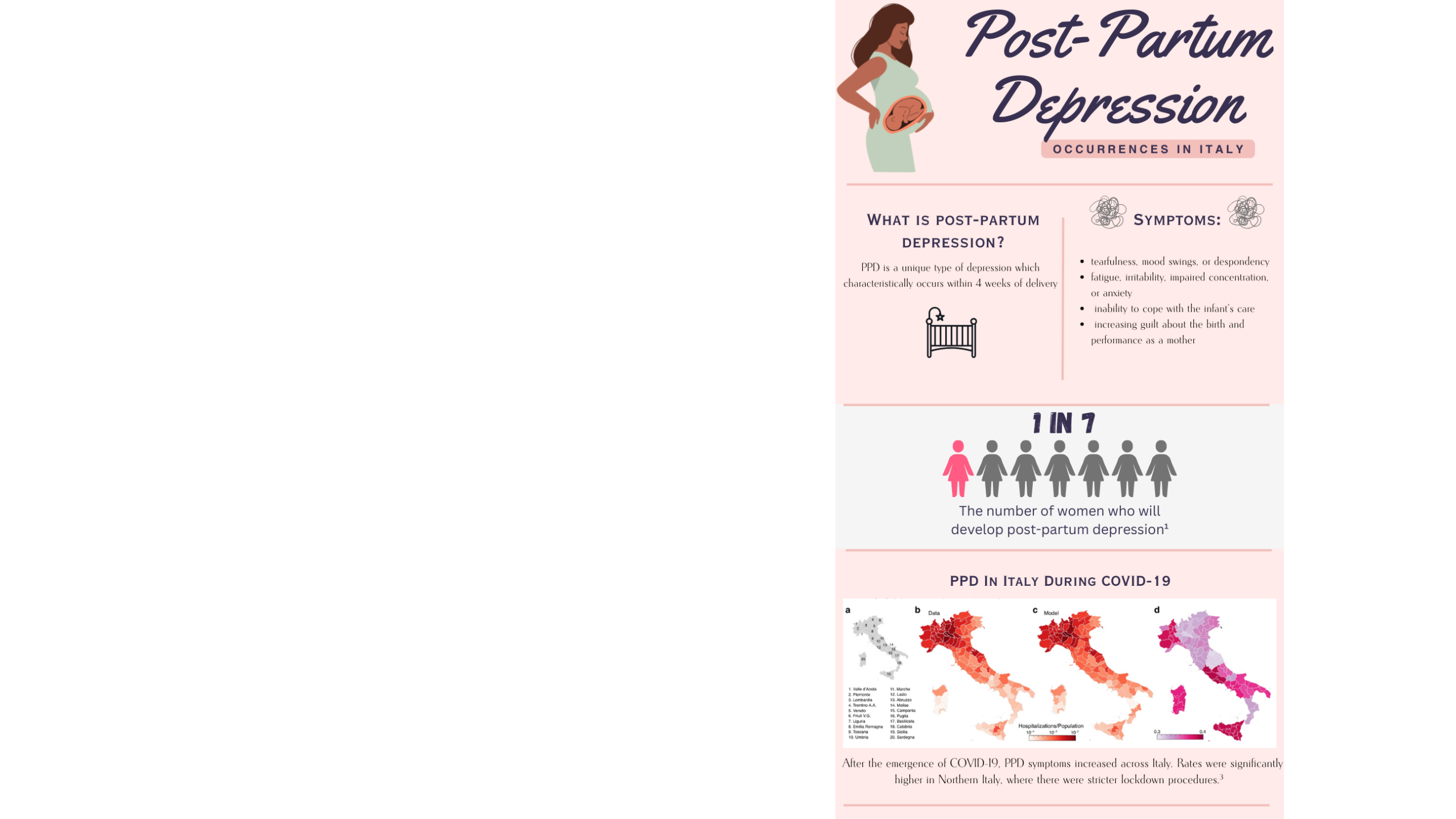

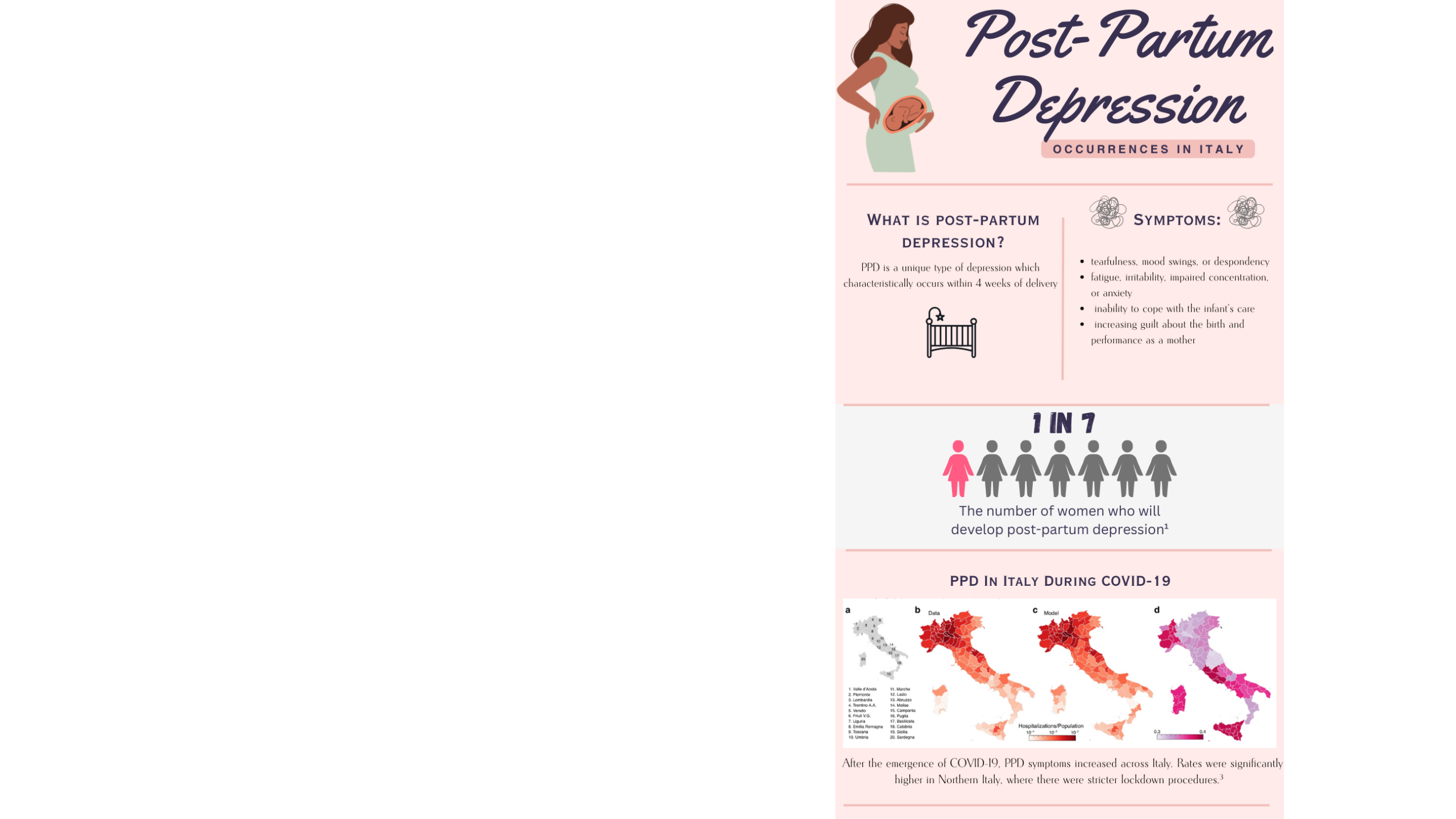

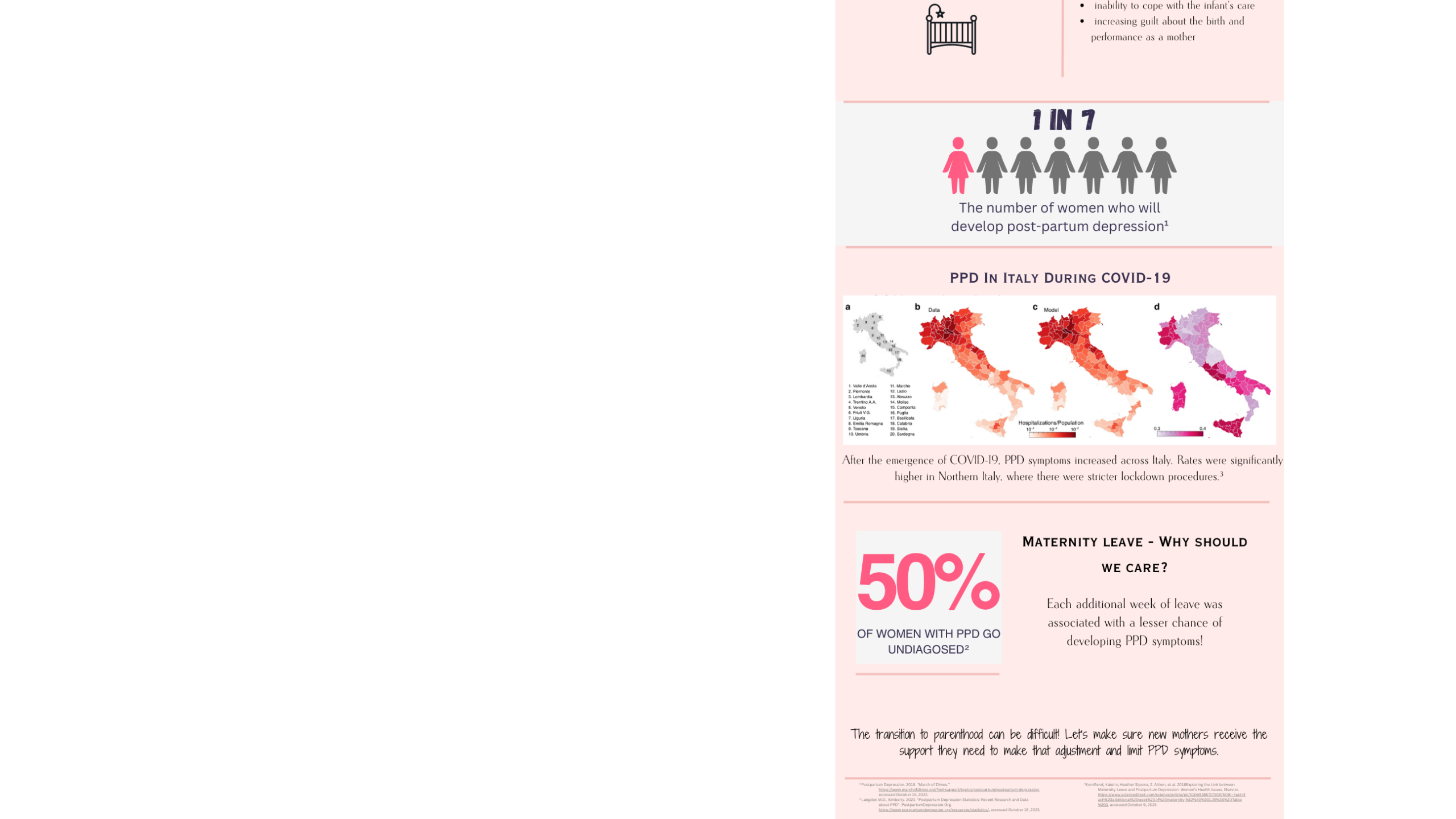

Post-partum depression (PPD) is a mental health epidemic that is often overlooked and tends to carry a negative stigma, possibly because it is a condition that is unique to pregnant women. According to the National Library of Medicine, the reality is that 1 in 7 women will develop post-partum depression, a unique type of depression that occurs within 4 weeks of delivery and is characterized by severe depression or mood swings, inability to sleep, intense irritability or anger, and difficulty bonding with their baby. One study performed in the United States found that for those who took leave of fewer than 12 weeks, each additional week of leave was associated with a lesser chance of experiencing PPD symptoms, showing that the duration of leave can be a protective factor (Kornfield et al. 2018). The maternity period is long and difficult, but the most critical and challenging time window in the postpartum period is approximately 12 months after birth (Spinola et al. 2023).

With the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in 2020, the country of Italy was perhaps hit the hardest of all European countries in terms of deaths, hospitalizations, and lockdown restrictions. During these periods of lockdown, there was a psychological impact on postpartum women, who showed higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to levels from before the onset of the nationwide lockdowns (Spinola et al. 2023). To the right is a map of Italy showing the distribution of hospitalizations across the regions of Italy in May 2020.

Occurrences of PPD symptomatology were found to be notably higher in the Northern regions of Italy, which experienced much more severe and prolonged periods of quarantine. As we move in from the periods of intense lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, the aim should be to mitigate the symptoms of PPD by providing mothers with adequate maternity leave and support via social policies. As mothers are the ones who tend to take on the role of primary caretaker for their children, a change in the mental health status of the mother such as post-partum depression may have developmental effects on the infant and their development.

Developmental Basis of the Infant

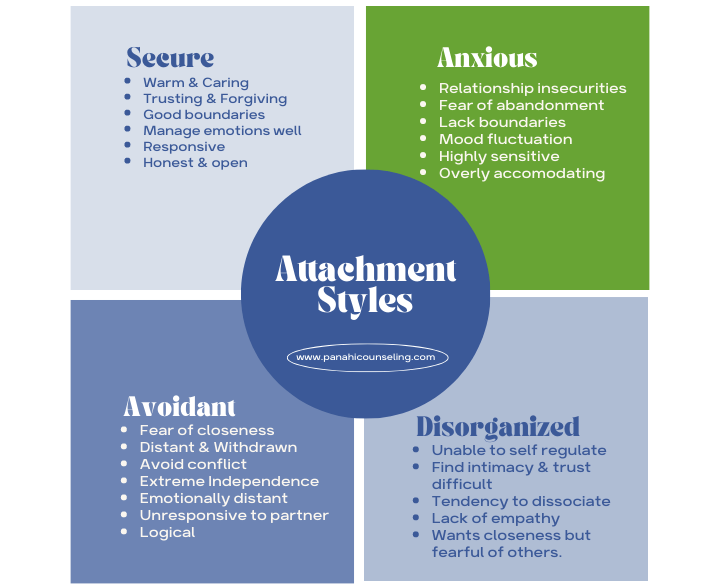

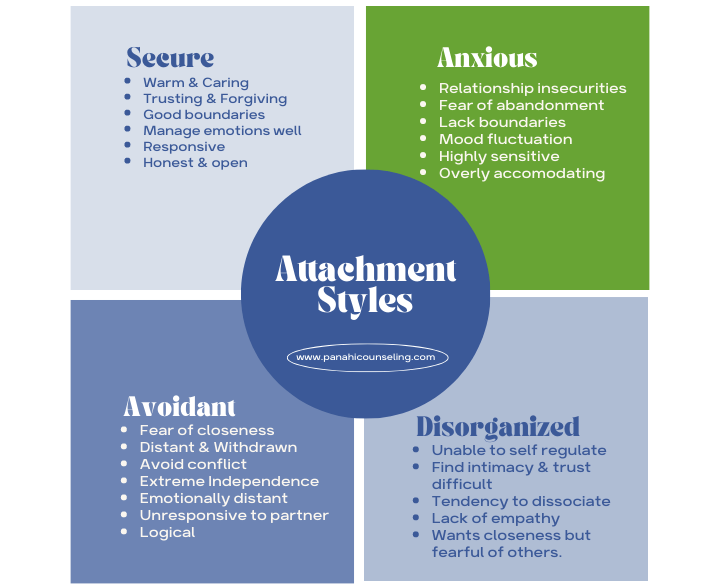

Adequate support during the maternity period is important not only for the mother but due to the inherent relationship between mother and fetus, these policies may also have developmental effects on the child. A recent study from Denmark discovered that a longer duration of maternity leave may have an overall benefit on infant health and wellbeing. On average, each additional month of maternity leave increased the well-being of children by up to 4.8% (CNE News 2023). Researchers also found that the children of mothers who remained home for longer periods had greater socioemotional skills. This may be because it encourages the development of a bond between mother and child and promotes the formation of a healthy attachment style. One of the most essential theories in psychology is Bowlby’s “Ethological Theory of Attachment”, which describes the formation of trust and attachment in infants. During the early periods of postnatal development, there is a critical period in which infants begin to form reciprocal relationships, which Bowlby believed has lifelong consequences on an individual's capacity to trust and feel secure.

There are four defined attachment styles, which are as follows: secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant, and disorganized/disoriented (Berk 2018). A secure attachment is the healthiest of the four attachment styles and can lead to improved cognitive, emotional, and social competencies later in life. The remaining insecure attachments are viewed as less ideal than the secure attachment type, with disorganized/disoriented attachments leading to the worst behavioral outcomes later in life. Individuals with this attachment style may reach adulthood and exhibit more antisocial or negative behavioral patterns, such as violence and aggression. With this in mind, researchers have found that there also seems to be a link between maternity leave and infant attachment types (Colin 1991). Infants were more likely to fall into the insecure category when mothers did not take maternity leave. Research has also identified that low levels of practical and social support for the mother may act as a factor that increases the risk of anxious attachments being formed. Hence, policymakers need to invest in the mental and physical health of the mother by passing maternity leave policies that support the transition to parenthood to encourage the best developmental outcome for the child.

John Bowlby, the famous psychologist who developed the "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Ackerman 2023).

John Bowlby, the famous psychologist who developed the "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Ackerman 2023).

John Bowlby, the famous psychologist who developed the "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Ackerman 2023).

John Bowlby, the famous psychologist who developed the "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Ackerman 2023).

The 4 attachment styles of John Bowlby's "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Panahi Counseling 2023).

The 4 attachment styles of John Bowlby's "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Panahi Counseling 2023).

The 4 attachment styles of John Bowlby's "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Panahi Counseling 2023).

The 4 attachment styles of John Bowlby's "Ethological Theory of Attachment" (Panahi Counseling 2023).

Paternity Leave

Another way to alleviate stress during the transition to parenthood is to also guarantee paternity leave, as it allows fathers to be more involved in the rearing of their children. Traditionally, women have been viewed as the primary caregivers and as such, are normally the ones in a relationship that are making sacrifices in regards to family and career. As they began to enter the workforce in the early 19th century, none of the work and domestic labor that they traditionally performed were delegated to others, meaning that they began to juggle productive and reproductive labor simultaneously. This view is especially prevalent in Italy, partially due to its Catholic influence, and the average Italian woman will take on almost three-quarters of the domestic work (Hornby 2012).

Other countries, such as Singapore, are taking the initiative and expanding their paternity leave policies by providing an additional two weeks of government-paid leave, doubling the original duration to a total of four weeks. A local study in Singapore found that paternity leave of 2 weeks or longer can lead to better family relations and fewer behavioral issues in children. As a result, these changes were implemented in the hopes of encouraging couples to have more children and promoting parental participation in the family (Lam and Bookmark 2023). Italy already provides 10 days of compulsory paternity leave, but increasing the duration and provisions of that leave may challenge traditional gender norms and show that parenting is a joint responsibility, creating better outcomes for both mother and child.

Conclusion

With falling birth rates across the globe, the best way to incentivize family building is to further progress social policies that support and provide resources to new mothers. Maternity leave provisions are medical necessities and a social right that allows for time off during and after the maternity period to adjust to the neurobiological and social changes that occur with pregnancy. Currently, many women are placed in a predicament in which they are constantly facing barriers that discourage them from having children. Stable jobs are difficult to come by, and as a dual family income becomes a necessity, many women are having to make the unfortunate choice between their careers and their family. At a minimum, providing paid maternity leave should be the universal standard in order to provide new mothers with time to recover from the laborious act of childbirth, and alleviate the financial burden incurred.

For countries like Italy which already have paid maternity leave policies, other provisions must be expanded upon to aid with the specific barriers in place within their culture. Further legislation to limit the use of loopholes and protect the jobs of mothers would be a major step in the right direction. In order to tackle the prevalent issue surrounding the availability of childcare, the Italian government has passed a bill that would provide 24 billion euros to public health services, including a tax break for mothers with over 2 children and a guarantee of nursery school for the 2nd child onwards (Za, Fonte, and Anzolin 2023). This is a monumental step to tackle what is perhaps one of the largest barriers in place for Italian families. In order to further ease the transition into parenthood, guaranteeing longer periods of paternity leave may allow for a more even distribution of work surrounding childcare and domestic roles by encouraging fathers to be more involved in the rearing of their children. While Italy already provides a compulsory paternity leave of 10 days, other countries have already taken the initiative to go beyond that as a means to level the playing field for both partners and to improve the wellbeing of children. Additionally, various types of social support can be protective of the mother's mental and physical health, which can lead to better outcomes for their children and their development, which will be reflected in their behavior as functioning adults in society. Hence why providing adequate support and progressive maternity leave measures is such a necessity, as we should be aiming to reduce the stress associated with the transition to parenthood.

Bibliography

[Accomplished_Hyena_6]. 2022. "How does Maternity/Paternity leave in your country work?" [Online Forum Post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/AskEurope/comments/yjsjc5/how_does_maternitypaternity_leave_in_your_country/

Ackerman, Courtney E. 2023. “What Is Attachment Theory? Bowlby’s 4 Stages Explained”. PositivePsychology. https://positivepsychology.com/attachment-theory/, accessed November 29, 2023.

Bartoloni, Stefania. 2015. “Women’s Mobilization for War (Italy)”. New Articles RSS. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/womens_mobilization_for_war_italy, accessed December 1, 2023.

Berk, Laura E. 2018. “Development Through the Lifespan, 7th Edition”. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

CNE News. 2023. Longer Maternity Leave Improves Well-Being of Children, Danish Research Shows.https://cne.news/article/3584-longer-maternity-leave-improves-well-being-of-children-danish-research-shows, accessed December 3, 2023.

Colin, Virginia. 1991. “Infant Attachment: What We Know Now”. ASPE. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/infant-attachment-what-we-know-now-0#:~:text=The%20, accessed October 15, 2023.

Deahl, Jessica. 2016. "Countries around the World Beat the U.S. on Paid Parental Leave”. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2016/10/06/495839588/countries-around-the-world-beat-the-u-s-on-paid-parental-leave, accessed November 6, 2023.

Doepke, Matthias, Anne Hannusch, Fabian Kindermann, and Michele Tertilt. 2022. “The New Economics of Fertility”. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Analytical-Series/new-economics-of-fertility-doepke-hannusch-kindermann-tertilt, accessed November 13, 2023.

Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. N.d. “Italy - Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion”. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1116&langId=en&intPageId=4618, accessed November 15, 2023.

Eurostat. 2023. Social Protection Statistics - Family and Children Benefits. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Social_protection_statistics_-_family_and_children_benefits#Family.2Fchildren_expenditure_in_2020, accessed November 29, 2023.

Gardey, Delphine, Margaret Maruani, and Monique Meron. 2022. “Earning a Living in Europe during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A Question of Gender”. Encyclopédie d’histoire Numérique de l’Europe. https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/gender-and-europe/earning-a-living/earning-a-living-in-europe-during-19th-and-20th-centuries-a-question-gender, accessed December 1, 2023.

Ginsburg, Faye, and Rayna Rapp. 1991. “The Politics of Reproduction”. Annual Review of Anthropology (20;1): 311-343. https://www-annualreviews-org.proxy.binghamton.edu/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.an.20.100191.001523, accessed October 23, 2023.

Gnot, Maurizio. 2011. “Italy - Maternity Protection”. TRAVAIL Legal Databases. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/travail/travmain.sectionReport1?p_lang=en&p_structure=3&p_year=2011&p_start=1&p_increment=10&p_sc_id=2000&p_countries=IT&p_print=Y, accessed December 12, 2023.

Hernandez, Christine. 2023. “I Hid My Pregnancy and the Existence of My Second Child from My Job. Here’s Why.” HuffPost UK. HuffPost UK, October 9. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/i-hid-my-pregnancy-and-the-existence-of-my-second-child-from-my-job-heres-why_uk_64fb0b35e4b06deaa9848349

Hornby, Catherine. 2012. “Italian Women Hope for Workplace Changes Post-Berlusconi”. Reuters. Thomson Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-women/italian-women-hope-for-workplace-changes-post-berlusconi-idUSTRE81D0W420120214/, accessed November 13, 2023.

INAPP News - Indagine PLUS: Presentato Il Nuovo Rapporto. 2023. “INAPP Newsletter - National Institute for Analysis of Public Policies”. https://www.inapp.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/Non-organizzati/INAPPNews_3_23.pdf, accessed November 13, 2023.

Kornfiend, Katelin and Heather Sipsma. 2018. “Exploring the Link between Maternity Leave and Postpartum Depression”. Women’s Health Issues (28;4): 321-326. Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1049386717304760#:~:text=Each%20additional%20week%20of%20maternity,%E2%80%931.29%3B%20Table%203, accessed October 9, 2023.

Lam, Nicole, and Bookmark. 2023. “The Big Read: Paternity Leave Helps but for Men to Take on Fair Share of Parenting, a Rethink of Gender Roles Is Needed”. CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/big-read-paternity-leave-men-parenting-fatherhood-family-gender-roles-3810696, accessed October 9, 2023.

Lowen, Mark 2021. “Italy’s Plummeting Birth Rate Worsened by Pandemic”. BBC News. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57396969, accessed December 4, 2023.

Mills, Mary Beth. 2003. “Gender and Inequality in the Global Labor Force”. Annual Review of Anthropology(31;1): 41-62. https://www-annualreviews-org.proxy.binghamton.edu/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093107, accessed October 23, 2023.

Nadeau, Barbie Latza, Valentina Di Donato and Antonia Mortensen. 2023. “‘Low Fertility Trap’: Why Italy’s Falling Birth Rate Is Causing Alarm.” CNN. Cable News Network, May 17. https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/17/europe/italy-record-low-birth-rate-intl-cmd/index.html, accessed October 23, 2023.

OCEM Family Database. N.d. “Pf2.5. Trends in Parental Leave Policies since 1970 - OECD”.https://www.oecd.org/els/family/PF2_5_Trends_in_leave_entitlements_around_childbirth.pdf, accessed December 4, 2023.

Pailhé, A., A. Solaz, and M.L. Tanturri. 2019. “The Time Cost of Raising Children in Different Fertility Contexts: Evidence from France and Italy”. Eur J Population. https://link-springer-com.proxy.binghamton.edu/article/10.1007/s10680-018-9470-8, accessed October 23, 2023.

Panahi Counseling. 2023. “What Is Your Attachment Style? A Guide to the Different Types of Attachments”. Best Counseling Services in Wheaton, Illinois | Panahi Counseling. https://panahicounseling.com/blogs/attachment-styles/, accessed November 29, 2023.

Salzano, Giovanni. 2023. “Italy Has the Lowest Female Labor Rate in European Union”. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-22/italy-has-the-lowest-female-labor-rate-in-european-union-chart?utm_source=website&utm_medium=share&utm_campaign=copy, accessed November 29, 2023.

Santacroce, Maristella. 2023. “Io, Mamma Senza Asili e Servizi Dovrò Scegliere Tra Carriera e Famiglia”. La Stampa. La Stampa. https://www.lastampa.it/torino/2023/10/12/news/io_mamma_senza_asili_e_servizi_dovro_scegliere_tra_carriera_e_famiglia-13778424/, accessed October 20, 2023.

Siegel, Mona L. 2019. “The Forgotten Origins of Paid Family Leave. The New York Times”. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/29/opinion/mothers-paid-family-leave.html, accessed September 29, 2023.

Shaw, Susan M., and Janet Lee. 2007. “Work Inside and Outside the Home”. Essay. In Gendered Voices Feminist Visions (457–524). NEW YORK: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Son, Keonhi. 2023. “The Origin of Social Policy for Women Workers: The Emergence of Paid Maternity Leave in Western Countries”. SageJournals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00104140231169024, accessed December 1, 2023.

Spinola, Olivia, Marianna Liotti, Anna Maria Speranza, and Renata Tambelli. 2020. “Effects of Covid-19 Epidemic Lockdown on Postpartum Depressive Symptoms in a Sample of Italian Mothers”. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589916/full, accessed October 9, 2023.

The Federal Register - Part 825. N.d. “The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993”. Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-29/subtitle-B/chapter-V/subchapter-C/part-825#825.306, accessed October 20, 2023.

Vezzosi, Elisabetta. 2007. “Why Is There No Maternity Leave in the United States? European Models for a Law That Was Never Passed.” The Place of Europe in American History: Twentieth Century Perspectives: 243-263.

Za, Valentina, Giuseppe Fonte, and Elisa Anzolin. 2023. “Insight: Job or Baby? Italian Women’s Struggle to Have Both Holds Back Growth”. Reuters. Thomson Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/job-or-baby-italian-womens-struggle-have-both-holds-back-growth-2023-10-13/, accessed October 20, 2023.