Ñeha’ãmbarete: The Survival of an Indigenous Language in Paraguay

A sociocultural and sociolinguistic analysis of how colonialism sometimes doesn't play out.

There's no better time to recoup your roots.

It’s not exactly right, calling myself Latina--but it’s not exactly wrong, either. My father was born and raised in a family that moved frequently between Paraguay and Argentina; he would end up marrying a girl from New York that would later become my mother. Her side of the family has lived in America for generations, and bears little cultural heritage to speak of. On the other hand, my parents have made considerable efforts to raise me in the most Argentine household they could. My Abuelos lived with us up until I turned nine, and for a long time I was exposed to a different Spanish than I would later learn in school. I never quite reached fluency in the language; perhaps it’s that loose end that drove me to major in it. In choosing to learn it in school, though, I lost a lot of the variation my family spoke. As I grew more skilled in Standard Spanish, I began to feel disconnected from the dialect I spoke as a child. There were next to no other Hispanic families at my school, so I never found a niche of kids I could properly speak with. To the other kids, I was Argentine. I bore too many cultural differences to be anything else. In Argentina, or even just groups of other Hispanic immigrants’ children, I was a gringa, an outsider. I always saw my identity as balancing between the stereotypical American and Argentine; I had never considered the possibility of a third facet. My abuela, though, has continued to speak to me in Paraguayan Spanish; she was born and raised in Asunción, its capital. As an adult, and a Spanish major, I began to notice a few of the regional phrases she would casually throw out while speaking. Things like porâ, or chipa guasu. They didn’t exactly sound Spanish, I thought at the time. When I asked her about it, she replied that she was speaking Guaraní. Furthermore, she said, our whole family has Guaraní heritage. It would turn out to be something of a rabbit hole, and since I received that answer I have developed an intense interest in learning more about Guaraní. This capstone serves in part as a reflection of my reconnection with my culture and family, in addition to simply answering a research question.

The research question that this capstone will answer is: How has Paraguayan culture affected that of the Guaraní, and vice versa?

The History of the Guaraní

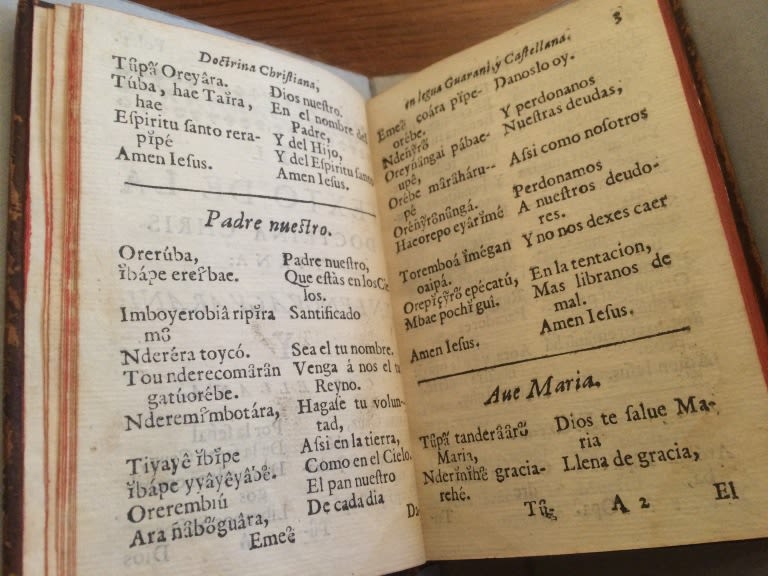

So what is Guaraní, really? It is an indigenous language belonging to the Tupi-Guaraní language family, and it belongs to the Guaraní people. The vast majority of Guaraní speakers live in Paraguay, which boasts it as one of the official languages. In fact, it is the only country in the Americas in which the majority of the population speaks an indigenous language. In its “pure” form, it bears no similarity to Spanish, though the two languages have undergone considerable changes in Paraguay. This can be attributed in part to the efforts of Jesuit missionaries, who in the 1600s took on the endeavor of evangelizing the Guaraní population that originally inhabited the region (Boidin et al., “This Book Is Your Book”). One missionary, Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, produced a number of lexical books that serve today as fundamental sources of Guaraní linguistic study (Nickson, Governance and the Revitalization of the Guaraní Language in Paraguay). In addition, the Jesuits created a semi-standardized written form of the language using the Latin alphabet; up until that point, it had been solely oral. Work and classes carried out in their missions took place almost entirely in Guaraní, and many of the written pieces left behind have furthered our modern knowledge on “pure” Guaraní, as opposed to the variant spoken today.

Thanks to books such as these penned by Jesuit missionaries, we have access to mostly-uninfluenced Guaraní, as well as valuable insight as to the state of society at the time of the book's writing. This specific volume features the Our Father and Hail Mary in both archaic Spanish and Guaraní.

Thanks to books such as these penned by Jesuit missionaries, we have access to mostly-uninfluenced Guaraní, as well as valuable insight as to the state of society at the time of the book's writing. This specific volume features the Our Father and Hail Mary in both archaic Spanish and Guaraní.

During the tumultuous period of civil and foreign violence that plagued Paraguay from the 1700s to late 1800s, Guaraní underwent several transformations in public opinion. Fernando de Mora demanded that Spanish dominate in Paraguay, while the country’s first president José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia advocated for the opposite (Ito, “With Spanish, Guaraní lives: a sociolinguistic analysis of bilingual education in Paraguay”). In wartime, Guaraní was regarded as a point of national pride: against Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, the distinguishing factor boasted by Paraguay was its language. As seen later in this paper, Guaraní has served as a source of community amongst Paraguayans, regardless of the government’s stance towards it. In an interview I conducted with a native Paraguayan (my own grandmother), we discussed the topic of Guaraní in the 1970s, at which point dictator Alfredo Stroessner was in power. For the duration of his rule, the language was prohibited from being spoken, adding to the lasting stigma against Guaraní. After the fall of his administration in 1989, Guaraní became one of the official languages of Paraguay.

Unfortunately, his legacy has persisted.

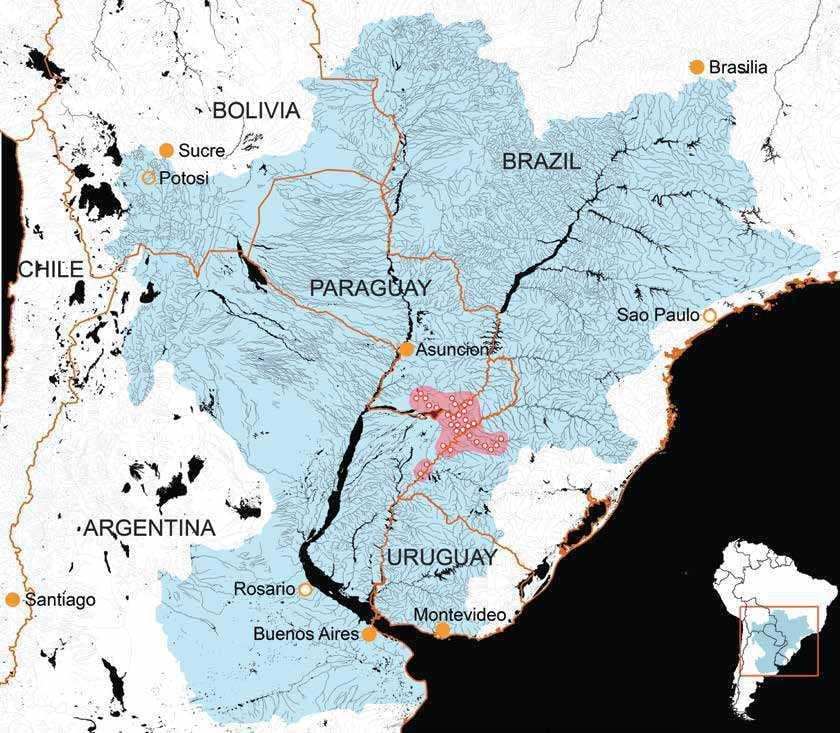

The blue areas represent the realm of Guaraní in the 17th century, whereas the red dots represent the spheres of influence enjoyed by Jesuit missionaries; each dot is one mission, known locally as a “reducción”. There were approximately 30 in total.

The blue areas represent the realm of Guaraní in the 17th century, whereas the red dots represent the spheres of influence enjoyed by Jesuit missionaries; each dot is one mission, known locally as a “reducción”. There were approximately 30 in total.

The Discrimination Situation

Discrimination comes in many forms.

So Guaraní is legal, taught in schools, and a shining example of indigenous preservation. The number of Guaraní Indigenous people– that is to say, those who don’t possess Spanish heritage, is significantly diminished. Most Paraguayans are a mix of Spanish and Guaraní, due to the high number of Spanish men fathering children with the local women. The majority of the population today is descended from those initial unions. What is most concerning, nowadays, is the level of discrimination aimed at Guaraní Indigenous people; regardless of the legalization of language, there is a persisting hierarchy of language and culture, in which Spanish is treated with greater legal and social privileges. In a statement by former UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the legal framework of Paraguay’s constitution “has not been translated into the legislative, administrative or other measures needed to ensure the enjoyment by indigenous peoples of their human rights, in particular their fundamental right to self-determination and their rights over their lands, territories and natural resources'' (Tauli-Corpuz, p.18).

Though this capstone focuses primarily on the culture of the Paraguayan population and language as a whole, it is important to acknowledge the contributions and sacrifices made by the natives who lived there first, and who continue to suffer. Unfortunately, the legal system of Paraguay allows for discrimination against indigenous peoples through delaying the implementation of tangible measures that may protect them. While the government of Paraguay may pay lip service to its indigenous population, the lack of support afforded to them suggests that improvements could be made. Tauli-Corpuz also speaks of the treatment they receive in cities, where “This attitude [of hostility] has been fueled by the plight of displaced indigenous peoples in the cities, where they find themselves in difficult straits.”(p.12). The general population as a whole also suffers from a more diluted form of discrimination, manifested in part by high poverty rates in areas where Guaraní is most widely spoken. The need for employment drives them to the cities, where Spanish–and therefore, colonialist institutions– are more widely evident, and where discrimination is more overt.

Special Rapporteur Tauli-Corpuz giving a statement on the difficulties suffered by indigenous peoples due to the COVID-19 pandemic

Special Rapporteur Tauli-Corpuz giving a statement on the difficulties suffered by indigenous peoples due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The Commodification of Guaraní

For better or for worse.

Regardless of the discrimination leveled at Guaraní speakers, the sheer quantity of them–approximately 5.5 million–means that the culture is important to the economy. That holds true in more ways than one: the Paraguayan currency is called a guaraní (plural guaraníes), while one of the oldest and most successful soccer teams in the country bears the same name. These are two of the most prominent examples of performative respect, in which the Guaraní are referred to but do not benefit from the use of their name. Aside from that, there are products and services made by and for people of Guaraní descent that contribute in kind to the economy.

For example, Duolingo recently released a course on Guaraní for Spanish speakers, which also helps revitalize the culture for individuals who might wish to reconnect with their roots as I do. I contacted a translation company, called TransPerfect, that offered Guaraní as one of the possible languages; I was curious as to how often they received requests for it. The response of the representative Lia Toma was “not that often, as you may guess. However, when it does happen, it’s mainly a request for translation of clinical research”(Toma). Increasingly popular is the trend of dubbing and subtitling TV shows and movies in Guaraní. One of Paraguay’s most prevalent commodities, dating back to pre-colonial times, is tereré.

Tereré is a blend of yerba mate and herbs native to Paraguay, and is one of the most widely consumed drinks in the country. Mate is prevalent in much of southern South America, and has come to be almost synonymous with Paraguayan, Argentine, and Uruguayan culture. In fact, “Jesuit missionaries noticed its value to their indigenous laborers and planted it alongside other agricultural commodities at their missions”, according to an article published by Kendrick Foster at Harvard. Indigenous peoples, the Guaraní among them, were the first to make use of the plant; it is through them that the tri-country area developed such a strong cultural connection to the drink (it’s even the national drink of Paraguay), and it was the Guaraní who added medicinal herbs to mate to make tereré. Further related to the Guaraní, two Jesuit missions were designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites: La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue (UNESCO). Revenue is being brought in through tourism largely because of the native Guaraní and the Jesuits that worked with them; it is considerations like this that indicate the cultural and economic importance of the Guaraní to Paraguay.

Socioeconomics of the Guaraní

Knowing this, it may come as something of a surprise that Guaraní people experience such drastic poverty in comparison to the rest of the country. Indeed, Paraguay is not a terribly wealthy country, and rampant inflation further exacerbates the issue. The current exchange rate of guaraníes to USD is 6,818.56 : 1, according to Google. Add that to what we know about indigenous poverty rates in Paraguay: “The rates of poverty and extreme poverty among Indigenous Peoples are 75% and 60% respectively, which far exceeds the national average. As for the situation of children under the age of five, the rate of extreme poverty is 63%, compared to the 26% national average, and the rate of chronic malnutrition is 41.7%, compared to a 17.5% national average”, according to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

Separate from the Guaraní Indigenous are the Guaraní speakers, who have indigenous heritage but who don’t live in indigenous communities. These speakers–namely monolingual ones who speak little or no Spanish– are most often located in rural areas, suggesting a disturbing correlation between the language, the location, and poverty. With fewer opportunities, they are forced to move either to the city or, also commonly, to neighboring Argentina. In an interview with Maria, a woman from rural Paraguay, she recounts coming to Argentina “to have a better life” (WIKITONGUES: María speaking Guarani, 0:30-0:32). However, due to inflation in both countries and general poverty, she is unable to return to her family. Maria’s story is not uncommon, as the border between Argentina and Paraguay promises potential riches to many of those under the poverty line. That’s partly why my abuela moved to Argentina, too.

Here, however, is where we begin to run into the clash between languages. Guaraní is a language that is spoken in mainly informal contexts; jobs that require more “sophisticated” languages are typically conducted in Spanish. This presents a socioeconomic barrier for those who speak only Guaraní, as higher-paying jobs may be inaccessible to them. Contribution to Paraguayan culture, no matter how significant, has not resulted in proportional gains for those who speak Guaraní or are Guaraní; “the economic power of Paraguay remains guarded in the hands of elites, and the common people who speak its language receive nothing,” says my abuela, upon being asked about the economy. The economic elite has something to learn about gratefulness, it seems.

Where can Guaraní be found, then, if not in white-collar workplaces? The answer to that is: everywhere else. Though the language has been outlawed several times over the course of Paraguayan history, it has been passed down through generations in households and on the street. As mentioned before, it has been used as something of a lynchpin of Paraguayan pride; regardless of its legality, many people find it to be an integral part of their culture and identity. Though efforts have been made to bring Guaraní into the spotlight by the Paraguayan government, a certain stigma around speaking it publicly has persisted, especially with older generations that were forced to hide their knowledge of the language during the reign of Stroessner. When asked about this, specifically, my abuela responded that “you would speak it in your house, but you would have to be careful to only do so around those you trusted. A lot of parents would punish their children for speaking it openly”.

Beginning in the 1990s, the constitution has included articles such as National Collective Linguistic Rights, which includes segments such as “Have a Guaraní-Spanish bilingual education plan throughout the national education system, from initial to higher education, and with differentiated plans for indigenous peoples”(Language Law. Nº 4251, Art. 10). Since then, a bilingual education system has been implemented, though its execution has been somewhat flawed. Interestingly, the main flaw has not rested on students not knowing Guaraní; on the contrary, according to a study referenced by Nickson, “an official evaluation of the quality improvement program for secondary education noted that many students were bilingual in name only and were in fact confident only speaking in Guaraní”.

Issues emerge with students receiving insufficient education as a result of the bilingual system, which we see demonstrated when they are unable to get jobs that require fluent Spanish. Reportedly, the reception of bilingual education in the 90s was lackluster, owed in part to “confusion and disagreement concerning the overly academic form of Guaraní and the wealth of neologisms used in the language instruction manuals [given to teachers]” (Nickson). The Guaraní being taught in schools is not necessarily the same language being spoken on the street and in homes: taking the evolution of language into effect, the “pure” form being taught lacks the Spanish influence that marks the form of the language widely spoken today. This, I believe, is one of the reasons the bilingual academic system has not been as successful as it could have been: neither of the languages being taught were necessarily the language people knew.

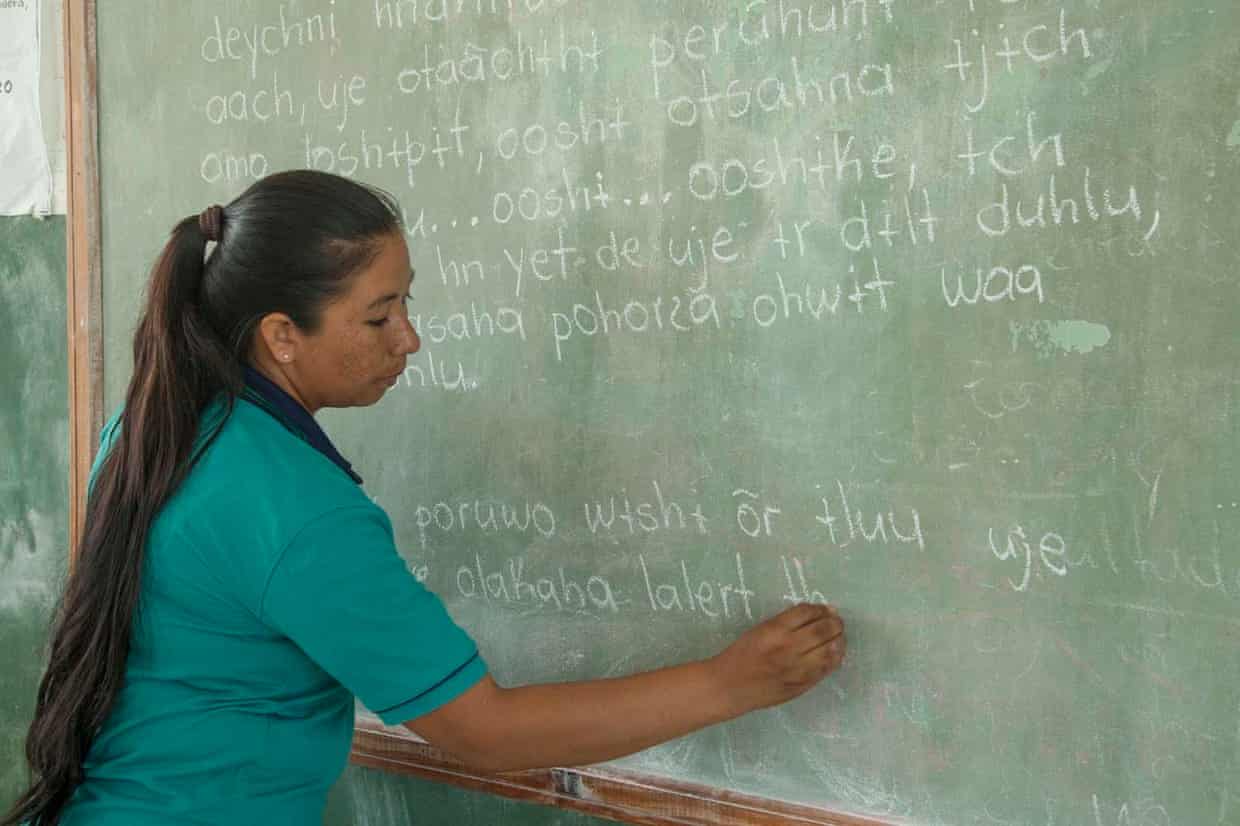

In a Paraguayan classroom such as this, classes may be taught in Guaraní or in Spanish, depending on a multitude of factors.

In a Paraguayan classroom such as this, classes may be taught in Guaraní or in Spanish, depending on a multitude of factors.

Sociolinguistics of Guaraní

What is the language people know, then, if not “pure” Guaraní? Nowadays, it’s called Yopará (or Jopará, depending on region). In Guaraní, the term means “mix”; it’s also the word for a lovely stew frequently eaten on the first day of October to ward off bad luck. Rather than meat and beans, though, the ingredients for this linguistic stew are Spanish and Guaraní.

With two languages in close proximity over the course of several hundred years, it should come as little surprise that some degree of diffusion would take place. Through unions between Spanish men and Guaraní women, a mixed population was born. There has been some debate on the survival of Guaraní; as stated before, the language spoken now is not the language that was spoken then. It would be more accurate to say that most people – in the cities, at least– speak Jopará, rather than pure Guaraní. Has the language truly been preserved, then? I would argue yes; having heard Jopará spoken as a fluent Spanish speaker, I can say with utmost confidence that I understood next to none of it. Though the incorporation of certain elements of Spanish may have changed the language from what it was in the 1700s, it has not “erased it entirely or turned it into a different form of Spanish,” as my abuela put it, when asked. In a study conducted by Hiroshi Ito, participants were asked about their perception of Spanish, Guaraní, and Jopara; “The majority of participants (i.e., parents, teachers, intellectuals, and policy makers) expressed negative views towards pure Guaraní and suggested the use of Jopará. Yet, the term Jopará seemed to be interpreted differently among policy makers and intellectuals” (Ito). Officials have used Jopará interchangeably with indiscriminate use of Spanish loan words, when the former is arguably stricter than the latter. It is a good thing to have access to pure Guaraní for research purposes, and in the name of cultural preservation, but in everyday life one must acknowledge that it is something of an archaic institution. Classes in the United States are not being taught in Shakespeare’s English; the language we speak today boasts a plethora of borrowed words. Though Guaraní is an indigenous language (and in a unique position at that), change does not necessarily indicate the language is devolving, as some have suggested.

Jopará can be made with a variety of ingredients, but beans and meat are frequently featured. Eating it on the first of October serves to ward off miseries, ailments, and general grievances. Like its linguistic counterpart, there is no standardized recipe.

Jopará can be made with a variety of ingredients, but beans and meat are frequently featured. Eating it on the first of October serves to ward off miseries, ailments, and general grievances. Like its linguistic counterpart, there is no standardized recipe.

A Brief Linguistic Analysis of Jopará and its Parents

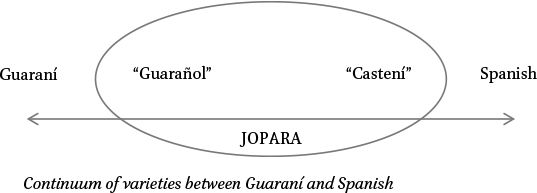

Is there a way to standardize Jopará? It is upon this question, I believe, that its status rests. Guaraní bears zero resemblance to Spanish, and yet the two have mingled enough to create something new. The grammar of the two languages bears few similarities; it’s fascinating to be able to see it in action. Depending on location, speaker, and situation, the level of either language can vary. In fact, “Jopará” might serve as more of an umbrella term of a wider spectrum: in a paper published by Bruno Estigarribia in 2015, he mentions “the usefulness of terms like Guarañol and Castení to describe particular kinds of Guaraní-Spanish [codeswitching], and suggesting to reserve the term Jopara as an overall term for the mixed lect derived from Guaraní-Spanish [codeswitching]”(Estigarribia, Guaraní-Spanish Jopara Mixing in a Paraguayan Novel).

Rather, a variety of terms might be used so as to further clarify the level of linguistic mixing, as illustrated in the figure above. I asked my abuela what she would classify her speech as; she replied that what she spoke on the streets most qualified as Castení– that the majority of the people she knew would describe their own experiences similarly–, but that when she was home it ranged more towards Guarañol. This corresponds to the cultural impact of Stroessner’s reign, where speaking Spanish was the safe option; after all, it’s far easier to dismiss a word or two of Guaraní in your speech than a whole sentence. As an example of one of the differences between the two languages, Guaraní functions largely upon the use of affixes to change meaning, whereas Spanish functions upon a wide lexicon of words; this leads to an interesting play between them (Estigarribia, Guarani Morphology in Paraguayan Spanish: Insights from Code-Mixing Typology). Taking an example from Estigarribia, to say “quiero ete que sea feliz” makes use of the suffix “ete”, meaning “so much”, to change the meaning of the phrase “I want you to be happy” to “I want so much/very badly for you to be happy”(Estigarribia, 54).

Conclusion

To answer the question posed at the beginning, Guaraní– both the language and the people– are intrinsically linked to Paraguayan culture. It is a point of pride among its populace– at least, it is outwardly. The internal power struggle connected to the language speaks to the flawed nature of the Paraguayan government; when acted upon by an outside force, though, Paraguayan culture hinges on its indigenous history. The Guaraní were there first, after all; without the threat of enslavement by the Spanish, the Jesuits would never have had reason to preserve the Guaraní language in the first place. The fact that they did, though, has resulted in something of a unique sociological situation. In a continent where Spanish is so readily synonymous with spoken language, the widespread prevalence of Guaraní serves as a bittersweet reminder that there were once hundreds of tribes and groups whose languages didn’t manage to make it to official status. Even Guaraní, official though it may be, didn’t escape the process of colonization unscathed. Spanish dominance in South America has resulted in systemic discrimination agains the Guaraní and Paraguayan speakers of their language; one may argue any number of perspectives, but the current state of affairs indicates that the Guaraní spoken pre-colonization has not been spoken for many years now, and most likely will not be spoken in the years to come. That is Paraguay’s (and by extension, Spain’s) influence at hand, in conjunction with the racism and colonialist values that succeeded at eliminating so many indigenous tribes from other areas of the continent. There are, of course, still cultural elements of the Guaraní that shine through in the cities: the food, the art, festivals celebrating the indigenous populations. Politicians are expected to be capable of speaking the language in order to be elected, though it’s rare that they would need to in the social circles a politician would grace. I firmly believe that Paraguayan culture would not hold up without the influence of the Guaraní, so deeply rooted is it– and that’s why I chose the title Ñeha’ãmbarete, to persevere: because as long as Paraguay remains its own country, that situation will never come to pass.

Works Cited

Boidin, Capucine, et al. “‘This Book Is Your Book’: Jesuit Editorial Policy and Individual Indigenous Reading in Eighteenth-Century Paraguay .” Ethnohistory, Duke University Press, 1 Apr. 2020, https://read-dukeupress-edu.proxy.binghamton.edu/ethnohistory/article/67/2/247/165743/This-Book-Is-Your-Book-Jesuit-Editorial-Policy-and.

Estigarribia, Bruno. “Guarani Morphology in Paraguayan Spanish: Insights from Code-Mixing Typology.” Hispania, vol. 100, no. 1, American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese, 2017, pp. 47–64, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26387675.

Estigarribia, Bruno. " Guaraní-Spanish Jopara Mixing in a Paraguayan Novel". Journal of Language Contact 8.2 (2015): 183-222. https://doi.org/10.1163/19552629-00802002 Web.

Foster, Kendrick. “Green Gold: Making Money (and Fighting Deforestation) with Yerba Mate.” Harvard International Review, Harvard International Review, 31 Aug. 2020, https://hir.harvard.edu/green-gold-yerba-mate/.

Gaona, Cairo, and Alicia Rebollo. 17 Nov. 2021.

Ito, H. “With Spanish, Guaraní lives: a sociolinguistic analysis of bilingual education in Paraguay.” Multiling.Ed. 2, 6 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-5059-2-6

Ito, H. “With Spanish, Guaraní lives: a sociolinguistic analysis of bilingual education in Paraguay.” Multiling.Ed. 2, 6 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-5059-2-6

“Ley De Lenguas. Nº 4251: Ko Léi Oñe'ẽ Ñane Ñe'ẽnguéra Léi Rehe. Nº 4251.” Secretaría Nacional De Cultura, Secretaria Nacional De Cultura, 15 Sept. 2011, http://www.cultura.gov.py/marcolegal/ley-de-lenguas-n%C2%BA-4251/.

Toma, Lia. 29 Nov. 2021.

Mediography

“Jug of Tereré and Guampa.” “Terere”, the Summer Mate, Kayari Yerba, 29 May 2020, https://www.kayariyerba.com/post/terere-the-summer-mate. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

Journal of Language Contact 8, 2 (2015) ; 10.1163/19552629-00802002

Paraguay Consume Jopara Para Ahuyentar Al Karaí Octubre, Radio Nacional Del Paraguay, 10 Jan. 2020, https://www.radionacional.gov.py/paraguay-consume-jopara-para-ahuyentar-al-karai-octubre/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

“Rows of Guaraníes.” Paraguay Currency Spotlight, The Current, 16 Sept. 2016, https://blog.continentalcurrency.ca/paraguay-currency/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

“Several Paraguayan High Schoolers Posing for the Camera.” Paraguay, AFS USA, https://www.afsusa.org/countries/paraguay/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

Silvetti, Jorge. “Map of Paraguay's Reducciones.” Revista, Harvard, 18 Mar. 2015, https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/first-take-shaping-the-guarani-territory/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

“The Our Father and Hail Mary, Translated by Jesuit Missionaries into the Guarani Language in One of the Earliest Catechisms Produced for Native American Peoples.” John J Burns Library, Boston College, 1 June 2015, https://johnjburnslibrary.wordpress.com/2015/06/01/lexica-jesuitica-3/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

“UN Special Rapporteur Victoria Tauli-Corpuz.” Tribal Link, Tribal Link, 5 May 2020, https://www.triballink.org/news/2020/5/7/message-of-the-un-special-rapporteur-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples-and-covid-19. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

Villalba, Mayeli. “Guaraní Being Taught in a Classroom.” 'Culture Is Language': Why an Indigenous Tongue Is Thriving in Paraguay, The Guardian, 3 Sept. 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/03/paraguay-guarani-indigenous-language. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.