Ecotourism in Costa Rica

How does ecotourism impact the environment and local socio-economic conditions in Costa Rica?

Costa Rica is often commended for being a model of conservation after eliminating their army in 1949 and pledging to commit to protecting their environment and supporting their people. In fact, many countries look to Costa Rica as a success story after they abolished their army and effectively reallocated their resources toward sustaining their land and people. A couple of decades after this decision, sustainable development in the late 1980s led to the rise of conservation policies and significant growth of the ecotourism industry by the mid-1990s (Wildes). Today, Costa Rica is well known for having a booming ecotourism business that strives to educate tourists about their native environment by employing local people. However, the current state of ecotourism is not working effectively everywhere. In order to remedy this, supporting local businesses and engaging in environmentally friendly activities are necessary and help avoid viewing the environment as important solely for its commercial value.

What is Ecotourism?

“responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education” (International Ecotourism Society)

Figure 3: Costa Rica Ecotourism

Ecotourism links conservation with local communities and tourism by including the following principles:

- Limiting physical and behavioral impacts on the local population

- Acquiring environmental and cultural awareness of the local population

- Developing positive experiences for visitors and hosts

- Financially supporting conservation efforts and the local people rather than big businesses

- Becoming involved in local experiences to develop an awareness of the host’s political, social, and environmental conditions

- Planning, developing, and running low-impact facilities

- Understanding the beliefs and rights of Indigenous People in the community and empowering them (The International Ecotourism Society)

How has ecotourism grown in Costa Rica?

In 2019, 2,511,824 people visited Costa Rica which is 690,000 more people than in 2013!

80% of people tend to visit for vacation or recreation purposes but some also visit for family (10%) or professional reasons (5%). (Instituto Costarricense de Turismo)

Where are tourists spending most of their time?

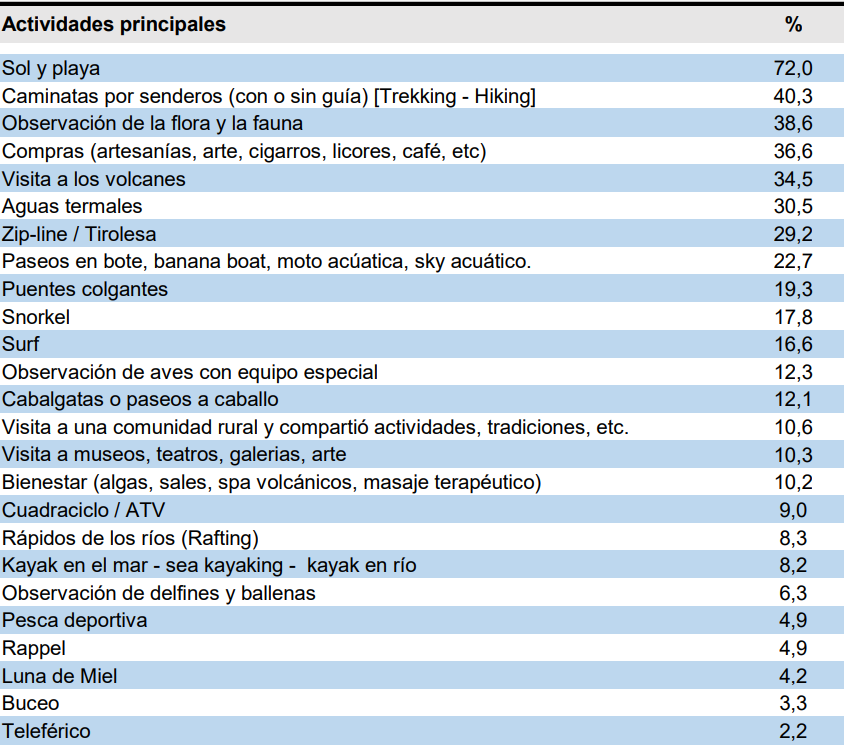

Most tourists (72.9%) tend to prioritize visiting beaches when in Costa Rica, hiking (40.3%), and observing the local wildlife and environment (38.6%). Shopping (36.6%), visiting volcanoes (34.5%), and ziplining (30.5%) are also popular activities. It is evident that most tourists want to take advantage of all that Costa Rica has to offer and be outside engaged in the local environment.

This certainly demonstrates the massive commercial value that can be applied to each of these areas as a result of tourists flocking here. In theory, ecotourism should assist the local people through job opportunities while also benefiting the surrounding environment through protection efforts which in turn exposes tourists to local sites through hiking or observing the native flora and fauna. However, local populations can often be negatively affected socially and economically by ecotourism as they are placed in low level jobs and may lack the business understanding to avoid selling their land to foreign companies. Similarly, a primary focus on the commercial value of an area or species can lead to inhibiting the progress of these species in exchange for economic gain.

Figure 2: Mayra Monge (right) Speaks with Student About Native Plants at Colegio Técnico Profesional in Upala, Costa Rica

Figure 2: Mayra Monge (right) Speaks with Student About Native Plants at Colegio Técnico Profesional in Upala, Costa Rica

Figure 4: Osa Peninsula Coastline

Figure 4: Osa Peninsula Coastline

Figure 5: Common Tourist Activities from 2017-2019

Figure 5: Common Tourist Activities from 2017-2019

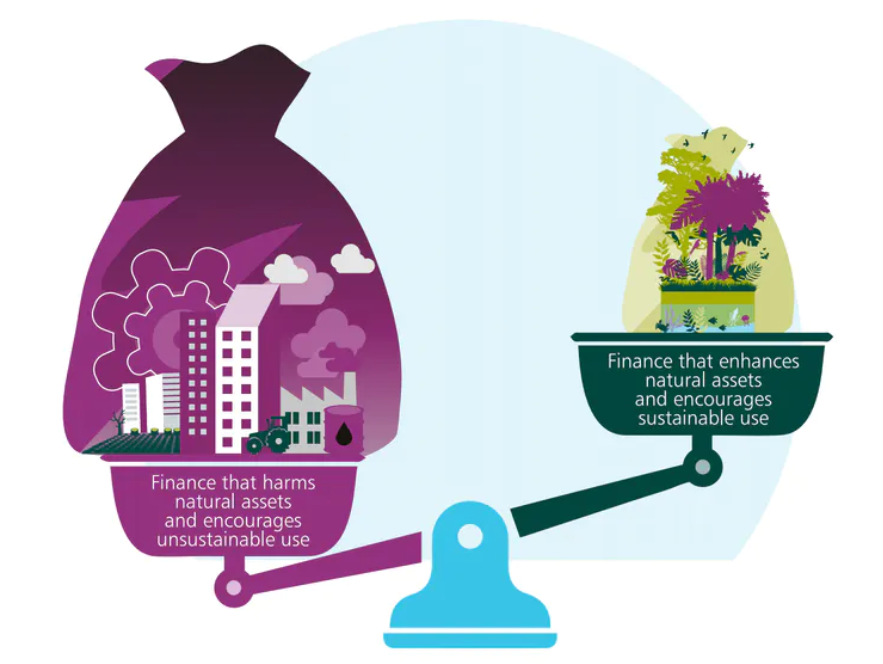

Figure 6: The Impact of Commercializing Natural Habitats

Figure 6: The Impact of Commercializing Natural Habitats

The History of Ecotourism in Costa Rica

Over time, Costa Rica has become more eco friendly especially after eliminating their military in 1949 and pledging to protect their people and the environment. 98% of all energy is renewable and deforestation has been reversed so currently over 50% of the land is covered in forest. 25% of the land is also protected through national parks and reserves demonstrating real government action after pledging to protect the environment (United Nations Environment Programme).

Deforestation was reversed in many areas especially in the Nicoya Peninsula following the Costa Rican government’s decision to stop subsidizing cattle ranching programs. Many households left the peninsula for better job opportunities since cattle ranching was no longer incentivized, demonstrating real government action to devote much of their energy and finances toward protecting the land. Cattle ranching is detrimental to the environment since cattle need land to graze and oftentimes end up overgrazing. This leads to erosion after compacting one area down over time and using up all of the available resources in this one area before moving to the next. Former cattle ranchers returned to the Nicoya Peninsula since they were influenced to work at the Punta Islita eco-lodge which provided a good source of employment after being promoted by the government (Almeyda 803). The eco-lodge which is “a type of tourist accommodation designed to have the least possible impact on the natural environment in which it is situated” (Oxford) can encourage more environmentally friendly jobs but also risks unintended harm to the environment from massive amounts of people flocking toward one region.

Figure 7: Woman Gazing up at Large Tree

Figure 8: Field of Grazing Cattle

Figure 9: Bird’s Eye View of Grazing Cattle in Costa Rican Forest

Figure 10: Local Tour Guide Plants with Young Tourist

Figure 10: Local Tour Guide Plants with Young Tourist

Figure 11: Osa Wild Workers Including Founder, Ifigenia Garita Canet (third person from the left)

Figure 11: Osa Wild Workers Including Founder, Ifigenia Garita Canet (third person from the left)

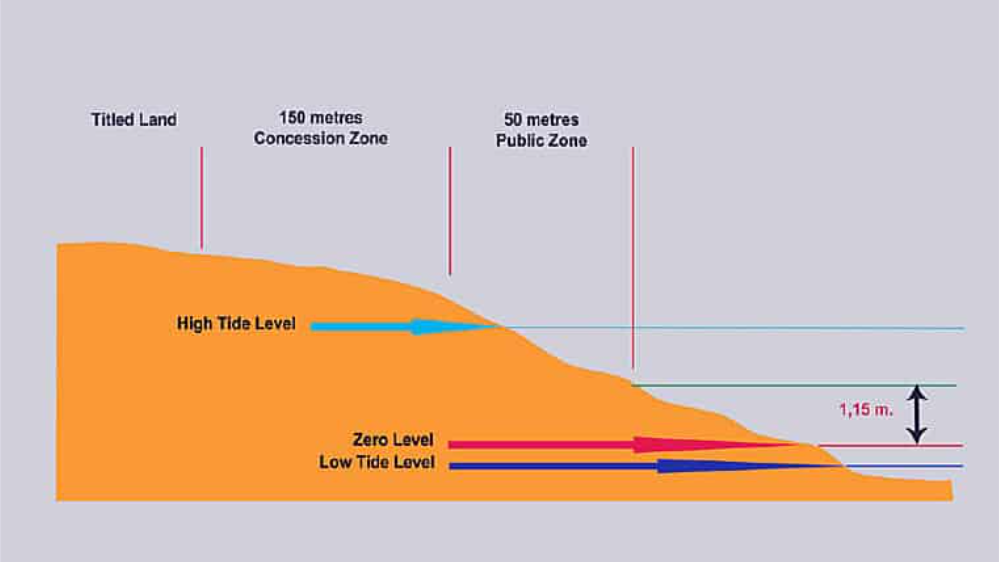

Figure 12: Maritime Zone in Costa Rica

Figure 12: Maritime Zone in Costa Rica

Figure 13: Curio Collection by Hilton in San Jose, Costa Rica

Figure 13: Curio Collection by Hilton in San Jose, Costa Rica

THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACT

Ecotourism provides a source of income and empowers local communities while simultaneously benefiting the environment through conservation efforts.

When following the principles of ecotourism that genuinely involve the local community, ecotourism “builds environmental awareness, generates direct and indirect financial benefits for conservation, revitalizes local cultures, and strengthens human rights and democratic movements” (Horton 95). If local people are able to provide services such as housing through an eco-lodge, tours such as bird watching or hiking, or educating tourists about their own cultural customs, everyone benefits. Not only are local people then financially supported but it is also possible that they advance socially and are able to spread their culture to visitors. The certificate of sustainable tourism was implemented in order to recognize exceptional management of these companies or organizations working toward reducing their environmental impact. Established in 1998, the certificate measures 152 factors within 4 main areas through yes or no questions when determining if a product, service, or facility meets their standards.

These 4 areas include:

- biological and physical surroundings (emissions and waste, policies and programs, green zones, and protection of flora and fauna)

- physical plant (management policies, water and energy consumption, waste management, and staff training)

- customers (guest facilities and instructions, management of groups, and feedback)

- social-economic environment (direct and indirect economic benefits, contributions to cultural development and health, and security) (Honey 11)

As a result, companies that abide by these rules and have attained the certification are viewed highly by others due to their strong commitment to the local community and environment. Local people are then able to spread their culture in a positive and engaging manner that is accessible to tourists and financially compensates them.

Yet... in reality, ecotourism does not always benefit the local population since foreign buyers are oftentimes favored due to their high prevalence and easy access to tourists.

I was fortunate enough to interview Ifigenia Garita Canet, a tropical biologist, activist, and founder of Osa Wild which is a travel company in Costa Rica supporting ecotourism through education, promoting local activities, and encouraging locals to preserve their land among other efforts. She spoke of how local people in Costa Rica may not have the best understanding of business and are prone to selling their land to foreign buyers for an immediate profit. Garita Canet helps them create their businesses on a greater scale by assisting with website development, explaining the importance of retaining their culture, and providing transparent advice. For example, selling to a foreign investor may seem like a lucrative deal since one gets money in hand immediately yet long term this takes more land out of the hands of local people and displaces them in order to make room for various developments. During our interview, Garita Canet explained that the government does not enforce many rules about how much land is able to be purchased by foreigners and instead advocates for further regulations.

In fact, “any foreigner, resident or non-resident has the same rights as a citizen, except for voting rights in presidential and municipal elections and can, therefore, purchase and own Costa Rica real estate legally” (Tico Times 1). The only exceptions to this rule are: a foreigner cannot own 100% of the land in a Maritime zone or purchase land donated to impoverished farm workers. The Maritime zone applies to property that is 150m away from the public protected land which stretches 50m away from the high tide line. As a result, up to 49% of land in the Maritime Zone is able to be purchased by non-citizens which is just less than half of the entire zone demonstrating limited regulation on purchases from foreign companies and people. The land donated to poor farmers is also able to be purchased by foreigners after the farmer has owned the property for 15 years. While there are some restrictions and zoning limits, much of these limitations stem from the fact that there is a large number of protected environmental areas through National parks or reserves. There appears to be more restrictions on where foreigners can purchase land due to environmental protection rather than who they can purchase land from since they are already legally allowed to buy land.

As a result of foreign companies buying large amounts of land in Costa Rica, the local people who could have become business owners for eco-lodges or knowledgeable tour guides are instead put into positions of working low wage jobs for other people, especially foreign companies on their own land. These jobs typically entail serving as hotel staff primarily as housekeepers or line cooks. Ecotourism can also disrupt family and social life for local people especially when they are working for a foreign company, specifically hotel chains or restaurants. For example, during busy seasons with large amounts of tourists, ecotourism workers such as cooks may need to work 15-hour or longer days which may differ from jobs with more traditional economic activities (Horton 101). This is a major issue since it inhibits the opportunities for local people as they are often taken advantage of by foreign businesses such as Hilton who are looking to expand their operations into Costa Rica after viewing the widespread economic success of ecotourism. Wealthy people in El Salvador, Europe, and the United States have all witnessed tourists travel to Costa Rica for its natural beauty with national parks and protected beaches leading to their desire to become involved and valuing the environment for what they can gain financially (Silk 1).

THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

Ecotourism promotes environmental protection.

The success of reforestation was possible following the initial concern of deforestation through “vigorous, continuing campaign to educate people on environmental and conservation issues, a deliberate strategy that began in the early 1970s with establishment of the initial national parks” (Wildes 179). General awareness of the problem and education to get the population involved motivated more people to become more environmentally friendly and establish protected areas and national parks. Public campaigning also allowed for the creation of government agencies such as the Ministry of Education, the Institute of Tourism (ICT), and the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mines (MIRENEM) that can enact real regulations and instill ideas of conservation in the public.

Nearly all of Costa Rica’s energy is already renewable so ecotourism only further enhances efforts to support the environment through sustainability measures which essentially allows for the current needs to be met without compromising the success of future generations. For example, the development of conservation areas, government support and tourism have been able to associate nature with an economic value preventing further deforestation. It is not in the country’s best interest to cut down trees which reduces biodiversity since the vast number of species and dense forests can be shown on tours. This allows the local people to profit off their surrounding environment through tourism and benefit from maintaining these areas rather than eliminating them.

The Institute of Tourism which has a branch in Costa Rica among other countries focuses on various certification processes for socially responsible tourism. These include the Certificate for Sustainable Tourism, the Ecological Blue Flag Program, and Code of Conduct. The Certificate for Sustainable Tourism logo entails a plaque with one to five leaves depending on how environmentally friendly a company is and consists of five certification levels emphasizing possible improvement (Honey 11). Established in France in 1985, the Ecological Blue Flag program analyzes the water quality, environmental management, environmental education, and safety of “beaches, marinas, and sustainable boating tourism operators” (Foundation for Environmental Education 1). The importance of the flag not only applauds a beach for their efforts and participation in the program but also shows their compliance with the four criteria. Similar certifications have been established in other countries such as the Nature and Ecotourism Accreditation Program in Australia which certifies products including accommodations, tours, and attractions rather than businesses on eight basic criteria. The criteria involves: natural area focus, interpretation, environmental sustainability, contribution to conservation, work with local communities, a cultural component, customer satisfaction, and responsible marketing (Honey 12). There are three levels of certification: nature tourism, ecotourism, and advanced ecotourism and approved products would have a logo indicating “Eco Certified.” Ecotourism has led to the establishment of many government policies and certification programs in order to inspire long term benefit to both the local people inhabiting an area and their surrounding environment.

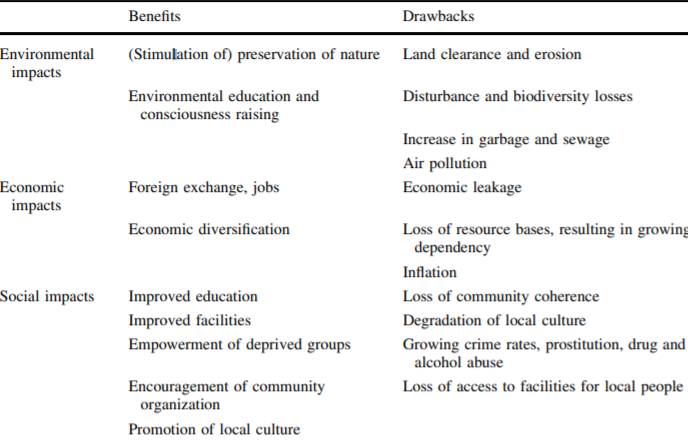

Yet... ecotourism can oftentimes degrade natural resources due to overuse, overexploitation, and long term damage.

Visiting a protected area can severely damage natural resources especially in areas with concentrated activities on trails or other recreation areas such as boating where captains frequently use the same route. This type of damage includes “trail proliferation, erosion and widening, muddiness on trails, vegetation cover loss, soil and root exposure, and tree damage on recreation sites” (Jeffrey and Marion 215). Essentially thinning occurs to the environment’s soil, roots, trees, and trails making it more difficult for regrowth to occur. This can be especially challenging when countries who have adopted ecotourism as their primary source of income like Costa Rica promise a pristine landscape yet there is also an increase of garbage and sewage or excessive land clearance in order to accommodate tourists. Not only is the natural environment disrupted by developing more buildings and facilities but animal life may also be disturbed by the swarm of people entering their home.

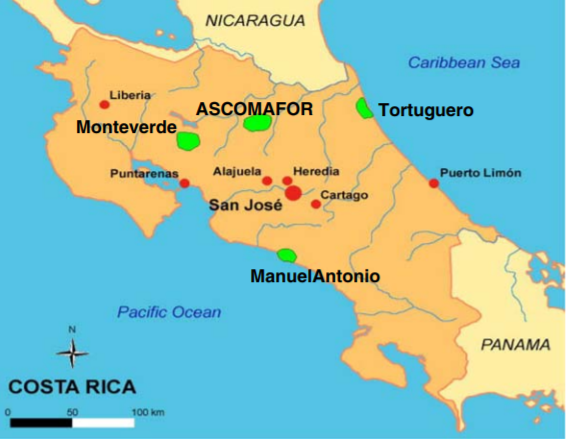

For example, beginning in the 1960s, tourism development has been a major factor in the Manuel Antonio region of Costa Rica due to its easy access and scenic landscapes. Tourism in the Monteverde region developed later in the 1980s and includes the threatened Tropical Montane Cloud Forest. Infrastructure and facility development in both the Manuel Antonio region and the Monteverde region has “led to vegetation damage, disturbance of wildlife and an increased possibility of erosion” (Koens, Dieperink, & Miranda 1230). While biodiversity has already been lost in the Manuel Antonio region, it is predicted that these losses will also occur in the Monteverde region fairly soon. The Tortuguero region made up of mostly swamp and tropical rainforest is the least visited due to its isolation where visitation is only possible by a forty-five minute boat ride. Land clearance has been a major issue in this region due to several hotels being built without adequate spatial planning.

The Manuel Antonio region

This region is unique in that it has experienced deforestation from agriculture, cattle ranching, and oil palm plantations but has also undergone reforestation due to the abandonment of land holdings and nature oriented tourism (Broadbent et al 731). Despite previous regeneration movements, the Manuel Antonio National Park is surrounded by palm oil plantations which have huge commercial value due to palm oil’s presence in foods, cosmetics, and detergents. Rapid rates of deforestation in order to provide room for these plantations limits the biodiversity of plants and animals since their habitats are being removed. Without a lush forest, many species will not be able to thrive demonstrating the importance of conservation for long term success with ecotourism in Costa Rica. While agricultural exports such as palm oil, bananas, and coffee are also important exports for the country, one must extract these resources at a lower rate than they are being produced in order to avoid environmental degradation.

The Playa Grande Region

Oftentimes, the large sum of tourists threaten what originally drew them to a particular region. For example, nesting turtles in this area are frequently frightened by huge groups of tourists that come to see them hatch. In fact, crowds of 50 or more people holding flashlights oftentimes will scare these turtles from the region permanently (Silk 2). These turtles are then displaced and must look for more isolated areas to lay their eggs, demonstrating how the economic gain of a growing tourist population can outweigh environmental protection. Ideally tourists could continue to go on these activities but must be educated in order to limit their harm to the region. While government involvement may be initially expensive, neglecting national park protection will allow for land exploitation and decrease ecotourism hurting the country’s economy in exchange for short term personal gain. This gain may involve hunting an endangered species since they are expensive or building more without sufficient planning but with hopes to accumulate the most profit. Regulations limiting the size of tourist groups and requiring that they be accompanied by local guides have been introduced to some regions but must be implemented elsewhere.

Although environmental degradation is especially problematic to Belize and Costa Rica since these countries “actively promote ecotourism and emphasize the pristine qualities of their natural resources” (Farrell and Marion 215), overuse is not a problem unique to Costa Rica. Any national park or heavily trafficked area by people runs the risk of becoming subject to some sort of environmental damage. As a result, we must be mindful in how we are interacting with this environment and the people running the national park could implement strategies in order to limit damage from human activities. For example, restricting camping or limiting the amount of people especially at one time to these areas are possible solutions.

Figure 14: Certificate for Sustainable Tourism Logo

Figure 14: Certificate for Sustainable Tourism Logo

Figure 15: Potential Benefits and Drawbacks of Ecotourism on the Environment

Figure 15: Potential Benefits and Drawbacks of Ecotourism on the Environment

Figure 16: Map of Popular Tourist Sites in Costa Rica

Figure 16: Map of Popular Tourist Sites in Costa Rica

Figure 17: Tourist Mob Blocks Turtles from Nesting in Canton Santa Cruz, Costa Rica

Figure 17: Tourist Mob Blocks Turtles from Nesting in Canton Santa Cruz, Costa Rica

What is the best way to optimize ecotourism? Eco-lodges!

Figure 18: Average Nights and Money Spent ($) on Housing from 2006-2020

Figure 18: Average Nights and Money Spent ($) on Housing from 2006-2020

In 2006, tourists spent $1,256.70 for 12 nights in Costa Rica in comparison to spending $1,592.10 for 12 nights in 2020. Housing is a major expense when traveling so it matters who that money is benefitting. Money generated can either support local Costa Rican people by flowing into their local economies or go toward foreigners that bought land in Costa Rica. While this appears to be more of a moral question, foreign companies are typically chosen by many tourists when visiting other countries due to their high prevalence, convenience, and ease when booking a room. However, increasing development in order to build these hotels in a region can oftentimes damage the surrounding environment especially when this development involves “standard hotel operations and large condo developments, seeks to capitalise on the region’s natural beauty and may reverse land cover trends if they are not accompanied by adequate forest conservation strategies” (Almeyda 803). Therefore, accommodations for tourists such as eco-lodges place the environment as the most important feature, employ local Costa Rican people, and are built to have a low impact on the surrounding area.

The Importance of Eco-lodges

The success of an eco-lodge can only continue if tourists utilize this type of housing rather than staying at large hotel chains which may not have the environment or local people’s best interest in mind. In fact, ecotourism is dependent on eco-lodges since their design and operation influences the natural environment. Eco-lodges are also run by Costa Rican people serving as an important form of employment. The primary goals of this form of housing involve: limiting the environmental effect, stimulating conservation, and improving the lives of local people by raising their social status, giving employment opportunities, and empowering them to maintain their culture.

Figure 21: Costa Rica's Eco Lodge

The Lapa Rios Eco-lodge

Well known for being a success story when it comes to environmental conservation and protection of workers, Lapa Rios raises the standards for ecotourism. The 1,000-acre rainforest reserve in the Osa Peninsula offers a variety of activities for guests from night hikes to a botanical garden to boat trips and tours of local wildlife. Owned by Karen and John Lewis, the eco-lodge has received the Certification for Sustainable Tourism as a result of their efforts to support both the local community and surrounding environment. In fact, Lapa Rios “puts the land they bought under protection, using low impact designs and technologies, hiring and training local people, and helping to build and support a community primary school” (Honey 8). Even OSA Wild founder, Ifigenia Garita Canet mentioned working for Lapa Rios in the past and applauded the eco-lodge for its efforts to genuinely engage in ecotourism.

The Punta Islita Eco-lodge

Similar to Lapa Rios, Punta Islita has been praised for benefiting the local community and surrounding area. Prior to the development of the eco-lodge, traditional tourism caused a rise in drug addiction, alcoholism, and prostitution but with the eco-lodge came a reduction of these behaviors. (Almeyda 803). Local people understood the value in maintaining the land leading to the Punta Islita eco-lodge property becoming the site of the most reforestation in the Nicoya Peninsula. The eco-lodge resulted in more migration back to this region by local Costa Rican people since it serves as a major form of employment.

Figure 19: Eco-lodge at Lapa Rios

Figure 20: Balcony View from Lapa Rios Bungalow

Figure 22: Punta Islita "Tamarindo" 2 Bedroom Villa

Conclusion

In order for ecotourism to genuinely work, it should “not only conserve the environment, but also improve the welfare of local people. It should generate money in an ecologically and socially friendly way than other forms of land exploitation” (Koens, Dieperink, & Miranda 1226). Ecotourism has become a major source of income for Costa Rica so political and social pressure exists in order to preserve this land for maximum economic benefits. However, one must be careful of overexploitation since this would terminate all sources of revenue from a given area. The success of ecotourism depends on further action from the Costa Rican government in order to enact more environmental protection programs and encourage conservation.

It is also our job as tourists to support local businesses rather than the foreign hotels that purchase the land from local Costa Rican people producing potentially harmful developments. Oftentimes, these large scale foreign companies not only damage the environment in the process of building but also limit local people’s economic success and social status. There are many eco-lodges available promoting a range of local experiences that include a variety of activities so there is something for everyone to enjoy. This form of housing is not only for people looking to adventure and spend as much time outside as possible by hiking or boating. Other less strenuous options are also available including spas and pools. Who benefits more from tourist dollars? The locally owned business or the large hotel chain established in many countries? It is more important to support the local community whose land you are visiting rather than spending money to benefit foreign owned companies such as Hilton. Foreign companies like this have viewed the environment as purely an opportunity for economic gain rather than something to protect while benefiting economically from. In order to avoid local people being taken advantage of, a knowledge of business is necessary for the local community as demonstrated through efforts from OSA Wild. This company strives to educate people and promote their businesses in order for local people to reap the maximum benefits from ecotourism since in order to fully maximize the benefits of ecotourism, “future research should be to explore incentives and impacts for both tourists and locals throughout all stages of tourism” (Stronza, 2001, p. 261). Overall, we need to be more conscious of where we are spending our money and how we interact with the environment in order to ensure long term involvement in these areas.

Figure 24: Lapa Rios Staff Showing Native Plant

Figure 24: Lapa Rios Staff Showing Native Plant

Figure 25: Hilton Hotel Becomes Tallest Building in San Jose, Costa Rica

Figure 25: Hilton Hotel Becomes Tallest Building in San Jose, Costa Rica

Figure 26: Lapa Rios Bungalow in the Forest

Figure 26: Lapa Rios Bungalow in the Forest

Figure 27: Dolphin Watching with Golfo Dulce Package Through OSA Wild Travel

Figure 27: Dolphin Watching with Golfo Dulce Package Through OSA Wild Travel

References

Almeyda, Angelica M., et al. “Ecotourism Impacts in the Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica.” International Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 12, no. 6, 11 Nov. 2010, pp. 803–819., https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.797.

Broadbent, Eben N., et al. “The Effect of Land Use Change and Ecotourism on Biodiversity: A Case Study of Manuel Antonio, Costa Rica, from 1985 to 2008.” Landscape Ecology, vol. 27, no. 5, 21 Feb. 2012, pp. 731–744., https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9722-7.

Certification for Sustainable Tourism. “What is the CST?” Turismosostenible.co.cr, https://www.turismo-sostenible.co.cr/.

Farrell, Tracy A., and Jeffrey L. Marion. “Identifying and Assessing Ecotourism Visitor Impacts at Eight Protected Areas in Costa Rica and Belize.” Environmental Conservation, vol. 28, no. 3, 10 May 2002, pp. 215–225., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0376892901000224.

Foundation for Environmental Education. “Pure Water, Clean Coasts, Safety and Access for All.” Blue Flag, https://www.blueflag.global/.

Garita Canet, Ifigenia. Personal interview. 10 August 2021.

Honey, Martha. “Protecting Eden: Setting Green Standards for the Tourism Industry.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, vol. 45, no. 6, 5 November 2012, pp. 8–20., https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2003.10544694.

Horton, Lynn R. “Buying up Nature: Economic and Social Impacts of Costa Rica's Ecotourism Boom.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 36, no. 3, 28 May 2009, pp. 93–107., https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582x09334299.

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo. “Statistics.” Instituto Costarricense De Turismo, https://www.ict.go.cr/en/statistics.html.

Koens, J. F., Dieperink, C., & Miranda, M. “Ecotourism as a Development Strategy: Experiences from Costa Rica”. Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 6, 8 October 2009, pp. 1225–1237, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-009-9214-3.

The International Ecotourism Society. “What is Ecotourism?” Ecotourism.org, https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/.

OSA Wild. “About Us.” Osa Wild Travel, https://osawild.travel/about-us/.

Oxford. “Ecolodge English Definition and Meaning.” Lexico Dictionaries, Lexico Dictionaries by Oxford, https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/ecolodge.

Silk, Steve. “Success Spoils Ecotourism in Costa Rica.” The Gazette, 31 August 1991, http://proxy.binghamton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/success-spoils-ecotourism-costa-rica/docview/432151141/se-2?accountid=14168.

Stronza, Amanda. “Anthropology of Tourism: Forging New Ground for Ecotourism and Other Alternatives.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 30, 2001, pp. 261–283, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3069217.

The Tico Times. “The 19-step Costa Rica Real Estate Guide for Foreign Buyers.” Tico Times, https://ticotimes.net/realestate/the-19-step-costa-rica-real-estate-guide-for-foreign-buyers.

United Nations Environment Programme. “Costa Rica: The ‘Living Eden’ Designing a Template for a Cleaner, Carbon-Free World.” Unep.org, 20 Sept. 2019, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/costa-rica-living-eden-designing-template-cleaner-carbon-free-world.

Wildes, Fred T. Influence of Ecotourism on Conservation Policy for Sustainable Development: The Case of Costa Rica, University of California, Santa Barbara, Ann Arbor, 1998. ProQuest, http://proxy.binghamton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/influence-ecotourism-on-conservation-policy/docview/304422896/se-2?accountid=14168.

Mediography (in chronological order)

Figure 1:

McMahon, Shannon. “Eco-lodge and Rafting in Costa Rica.” Smarter Travel, 7 July 2017, https://www.smartertravel.com/bucket-list-ecotourism-costa-rica/.

Figure 2:

Mora, Priscilla. “Mayra Monge (right) Speaks with Student About Native Plants at Colegio Técnico Profesional in Upala, Costa Rica.” The Global Environment Facility, 20 February 2020, https://www.thegef.org/news/life-lessons-cultivating-resilience-costa-rica.

Figure 3:

“Costa Rica Ecotourism.” YouTube, uploaded by Anywhere, 15 August 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zhsNtE00siA&list=PL8XHyYNhGWqOK5fhDDjIb74rp6bKkjAnm&t=6s.

Figure 4:

Mint Images - Lanting, Frans / Getty Images. “Osa Peninsula Coastline.” Q Costa Rica, 29 June 2016, https://qcostarica.com/osa-peninsula-costa-ricas-most-intrepid-corner/.

Figure 5:

Instituto Costarricense de Turismo. “Common Tourist Activities from 2017-2019.” Instituto Costarricense de Turismo, https://www.ict.go.cr/en/documents/estad%C3%ADsticas/cifras-tur%C3%ADsticas/actividades-realizadas/1404-principales-actividades/file.html.

Figure 6:

Dasgupta Review, CC BY-ND. “The Impact of Commercializing Natural Habitats.” The Conversation, 11 May 2021, https://theconversation.com/putting-a-dollar-value-on-nature-will-give-governments-and-businesses-more-reasons-to-protect-it-153968.

Figure 7:

Martin, Anne. “Woman Gazing up at Large Tree.” Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, 14 April 2017, https://blogs.nicholas.duke.edu/exploring-green/reforesting-the-land-in-costa-rica-and-rethinking-grazing/.

Figure 8:

Martin, Anne. “Field of Grazing Cattle.” Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, 14 April 2017, https://blogs.nicholas.duke.edu/exploring-green/reforesting-the-land-in-costa-rica-and-rethinking-grazing/.

Figure 9:

Martin, Anne. “Bird’s Eye View of Grazing Cattle in Costa Rican Forest.” Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, 14 April 2017, https://blogs.nicholas.duke.edu/exploring-green/reforesting-the-land-in-costa-rica-and-rethinking-grazing/.

Figure 10:

Earth Changers. “Local Tour Guide Plants with Young Tourist.” Earth Changers, https://www.earth-changers.com/sustainable-places/costa-rica-lapa-rios.

Figure 11:

OSA Wild. “Osa Wild Workers Including Founder, Ifigenia Garita Canet (third person from the left).” Osa Wild Travel, https://osawild.travel/about-us/.

Figure 12:

Pavones Life Realty. “Maritime Zone in Costa Rica.” Pavones Life Realty, https://pavonesliferealty.com/costa-rican-maritime-zone/.

Figure 13:

Hilton Hotels. “Curio Collection by Hilton in San Jose, Costa Rica.” Hilton, https://www.hilton.com/en/hotels/sjocuqq-gran-hotel-costa-rica/.

Figure 14:

Instituto Costariccense de Turismo. “Certificate for Sustainable Tourism Logo.” Instituto Costarricense de Turismo, https://www.ict.go.cr/en/sustainability/cst.html.

Figure 15:

Koens, J. F., Dieperink, C., & Miranda, M. “Potential Benefits and Drawbacks of Ecotourism on the Environment.” Environment, Development and Sustainability, 8 October 2009, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-009-9214-3.

Figure 16:

Koens, J. F., Dieperink, C., & Miranda, M. “Map of Popular Tourist Sites in Costa Rica.” Environment, Development and Sustainability, 8 October 2009, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-009-9214-3.

Figure 17:

Mountain, Jane. “Tourist Mob Blocks Turtles from Nesting in Canton Santa Cruz, Costa Rica.” Inhabit, 15 September 2015, https://inhabitat.com/mob-of-tourists-blocks-sea-turtles-from-their-nesting-ground-in-costa-rica/.

Figure 18:

Koens, J. F., Dieperink, C., & Miranda, M. “Average Nights and Money Spent ($) on Housing from 2006-2020.” Environment, Development and Sustainability, 8 October 2009, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-009-9214-3.

Figure 19:

Lapa Rios. “Eco-lodge at Lapa Rios.” Lapa Rios, https://www.laparios.com/eco-lodge-osa-peninsula/.

Figure 20:

Lapa Rios. “Balcony View from Lapa Rios Bungalow.” Lapa Rios, https://www.laparios.com/eco-lodge-osa-peninsula/.

Figure 21:

“Costa Rica’s Eco Lodge.” YouTube, uploaded by Smarter Travel, 17 December 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j49cqkKTSAo&t=35s.

Figure 22:

Punta Islita Hotel. “Punta Islita “Tamarindo” 2 Bedroom Villa.” Hotel Punta Islita, https://www.hotelpuntaislita.com/rooms-villas.

Figure 23:

Earth Changers. “Local Tour Guide Discusses Environment While Hiking.” Earth Changers, https://www.earth-changers.com/sustainable-places/costa-rica-lapa-rios.

Figure 24:

Earth Changers. “Lapa Rios Staff Showing Native Plant.” Earth Changers, https://www.earth-changers.com/sustainable-places/costa-rica-lapa-rios.

Figure 25:

Hilton San Jose La Sabana. “Hilton Hotel Becomes Tallest Building in San Jose, Costa Rica.” Hospitality Net, 14 May 2021, https://www.hospitalitynet.org/announcement/41006335/hilton-san-jose-la-sabana.html.

Figure 26:

Lapa Rios. “Lapa Rios Bungalow in the Forest.” Lapa Rios, https://www.laparios.com/eco-lodge-osa-peninsula/.

Figure 27:

OSA Wild. “Dolphin Watching with Golfo Dulce Package Through OSA Wild Travel.” Osa Wild Travel, https://osawild.travel/product/hands-on-golfo-dulce/.