Cute Girls and Soft Power:

AKB48's role in Japanese pop cultural diplomacy at home and abroad

Amanda Earls

Introduction

In this age of widely accessible information technology, conceptualizations of global power structures are rapidly evolving. No longer are our impressions of distant lands and people filtered through the words and cameras of a select few; on the contrary, many individuals in the developed world possess the capability to occupy international cultural spaces via the internet. This capability places increased importance on soft power in international affairs. Soft power, a term coined by Harvard professor Joseph Nye, is defined by US Foreign Service officer Hanscom Smith as “the use of culture, political values, and foreign policies to attract or influence, rather than coerce or induce, the behavior of others” (118). Nye himself defines culture as “the set of practices that create meaning for a society,” and identifies one possible manifestation of culture as “popular culture, which focuses on mass entertainment” (96). This manifestation is exemplified through the globalization of Japanese pop culture in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Cultural exports such as manga, anime, video games, and music not only expose the international community to the values of Japan, but contribute to the formation of hegemonic national identity both within Japan and abroad. According to Koichi Iwabuchi, sociologist and professor of Media and Cultural Studies at Waseda University, “increased media connection in Asia has encouraged people to critically and self-reflexively reconsider their own life, society and culture as well as socio-historically constituted relations and perceptions with others” (425). On the other hand, Iwabuchi also asserts that Japan’s pop culture diplomacy may garner “indifference, othering and antagonism” from international audiences (425). Therefore, it is most beneficial to examine Japan’s pop culture diplomacy through the lens of one specific export at a time so as to analyze in detail both negative and positive implications of domestic and international cultural impact.

Girl groups have been a staple of Japanese pop culture since the 1960s. In 1964, The French film “Cherchez L’idole” (Searching for an idol/ aidoru o sagase)’s depiction of young singer Sylvie Vartan popularized the term “idol,” transliterated into Japanese as aidoru. The decades since the film’s arrival have seen the rise and fall of numerous female pop idols, both as solo acts and in groups. Groups such as Candies, Pink Lady, Onyanko Club, Speed, and Morning Musume saturated the entertainment market with their catchy music, cute faces, and likeable personalities (whether genuine or performed.) In 2005, Onyanko Club producer Yasushi Akimoto founded a new concept for a locally-based idol group with a permanent theatre in the Akihabara district of Tokyo, a neighborhood famous for its underground popular culture. The group was named AKB48- AKB representing AKiBa, Akihabara’s nickname, and 48 representing the intended number of members. The group’s early years saw modest success, but it was not long before CD sales increased exponentially, allowing the group to surpass all other active idol groups in popularity. In fact, not a single one of the group’s singles has sold less than one million copies since 2011, and they are the highest selling musical act of all time in Japan (Kiuchi 32). However, music is not all they sell, and thus music is not their only contribution to Japanese pop culture. With a system of graduations and auditions, member popularity elections, in-person handshake events, ban on dating, and aesthetic which sexualizes girls as young as middle-school aged, AKB48 has a heavy influence on Japanese pop culture, but can be a difficult phenomenon for someone who is not familiar with Japanese pop culture to understand. Either way, the group’s incredible commercial success endows it with an immense capacity for cultural influence, leading to the question: what role does AKB48 play in Japanese pop culture diplomacy, and how does it impact contemporary interpretations of Japanese identity both within Japan and around the world? To answer this question, I will first examine the role AKB48 plays in the creation of Japanese national identity through analysis of their graduation and audition system, general elections, member sexualization, and ban on dating while in the group. I will then connect these topics to international interpretations of AKB48 through the lens of western news media case studies and the activities of overseas sister groups in order to evaluate the group’s success as “cultural diplomats” and interpret the image of Japanese culture it communicates globally.

Music Video for AKB48's 2009 single "River" (English closed captioning available)

All AKB48 members, 2017

All AKB48 members, 2017

Marquis in front of AKB48's permanent theatre

Marquis in front of AKB48's permanent theatre

General Elections

General Elections

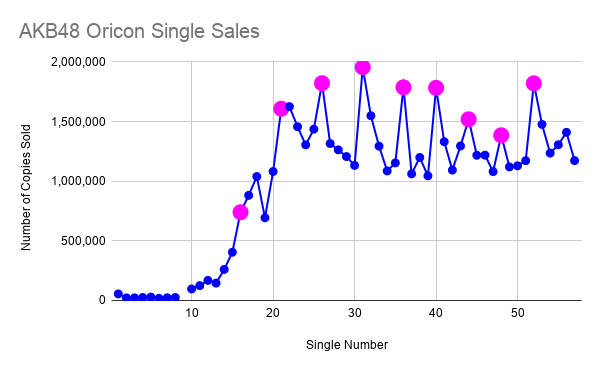

Hanscom Smith claims that Japan’s culture “boasts enormous strengths that have little to do with AKB48 and Naruto. The country’s most obvious—and oddly, mostunsung—attribute is a remarkable record of peaceful democracy” (119). However, this statement overlooks the role of democracy in the success of AKB48. Perhaps the most unique and innovative part of the 48 Groups is the senbatsu sousenkyo, or general election. Every year or two, fans are given the opportunity to vote for their favorite member. The members who choose to participate are then ranked from most to least popular, and members of different tiers of popularity are given different levels of opportunity to participate in promotional activities. While this sort of election holds little to no literal political significance, the cultural significance of incorporating democratic activity into the entertainment industry should not be underestimated. If Japanese citizens are disillusioned with national politics, the AKB48 election system gives voice to public opinion without the stress and conflict that often comes with the elections of political leaders, thus incubating national support for democracy. Voting is not free, however; each purchase of a designated CD grants the customer one vote. Mega-fans and those with cash to spare may invest in their favorite girl by buying hundreds, maybe even thousands of CDs. For example, one fan “reportedly spent US$6700 to secure 2700 votes in online auctions” to support his favorite member during the 2012 election. (McCurry). The graph below shows the number of CDs sold for each of the 57 major label singles the group has released. The large pink data points represent the singles preceding senbatsu elections, displaying a significant increase in sales when members’ status is at stake.

Source: Oricon

Source: Oricon

The commercial success of AKB48’s general elections suggests a cultural importance placed on democracy as a whole, and encourages individuals to uphold democratic principles outside of the political sphere. However, the costly nature of the elections has drawn criticism within Japan. A 16-year-old student interviewed by Asahi Shinbun compared the senbatsu sousenkyo mega-fans to “shareholders who have a bigger say if they invest more. It's not a genuine election."(McCurry). Even if this statement is true, it displays a potential positive effect of the elections: education about political and economic corruption.

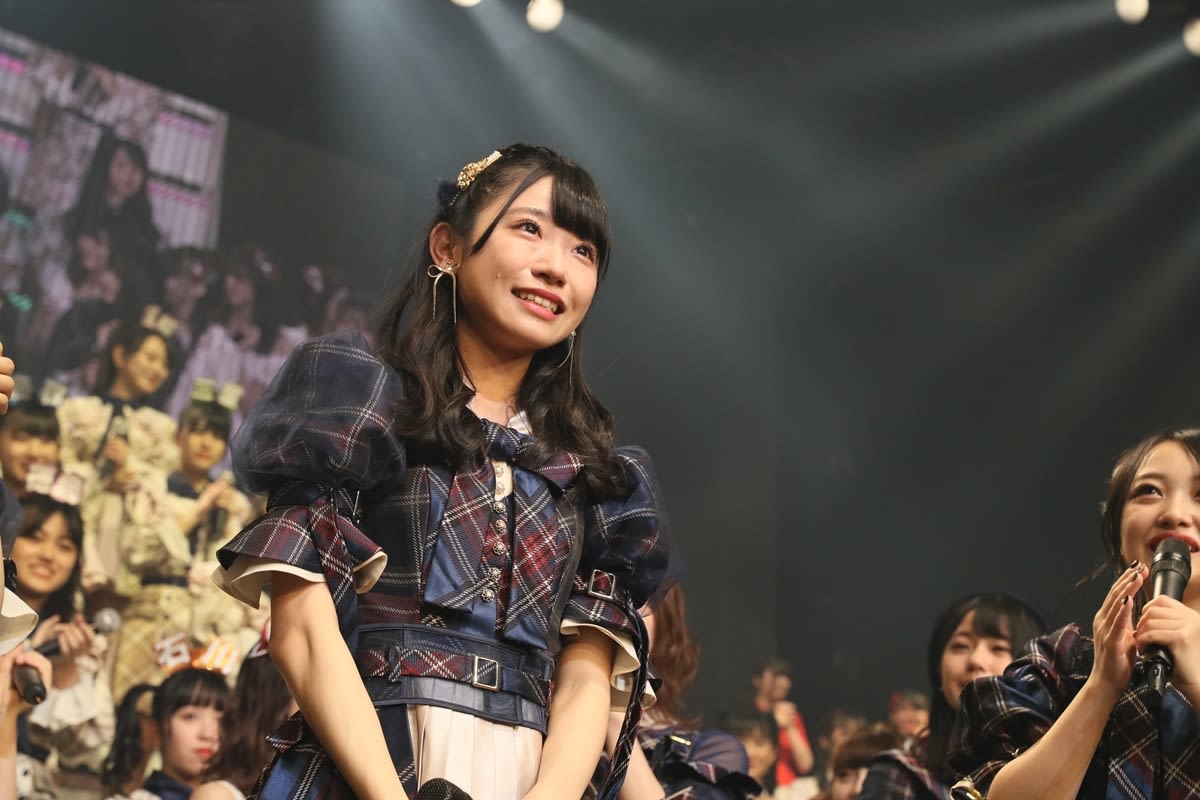

Jurina Matsui celebrating her ranking

Jurina Matsui celebrating her ranking

Rino Sashihara giving her acceptance speech

Rino Sashihara giving her acceptance speech

Graduations and Auditions

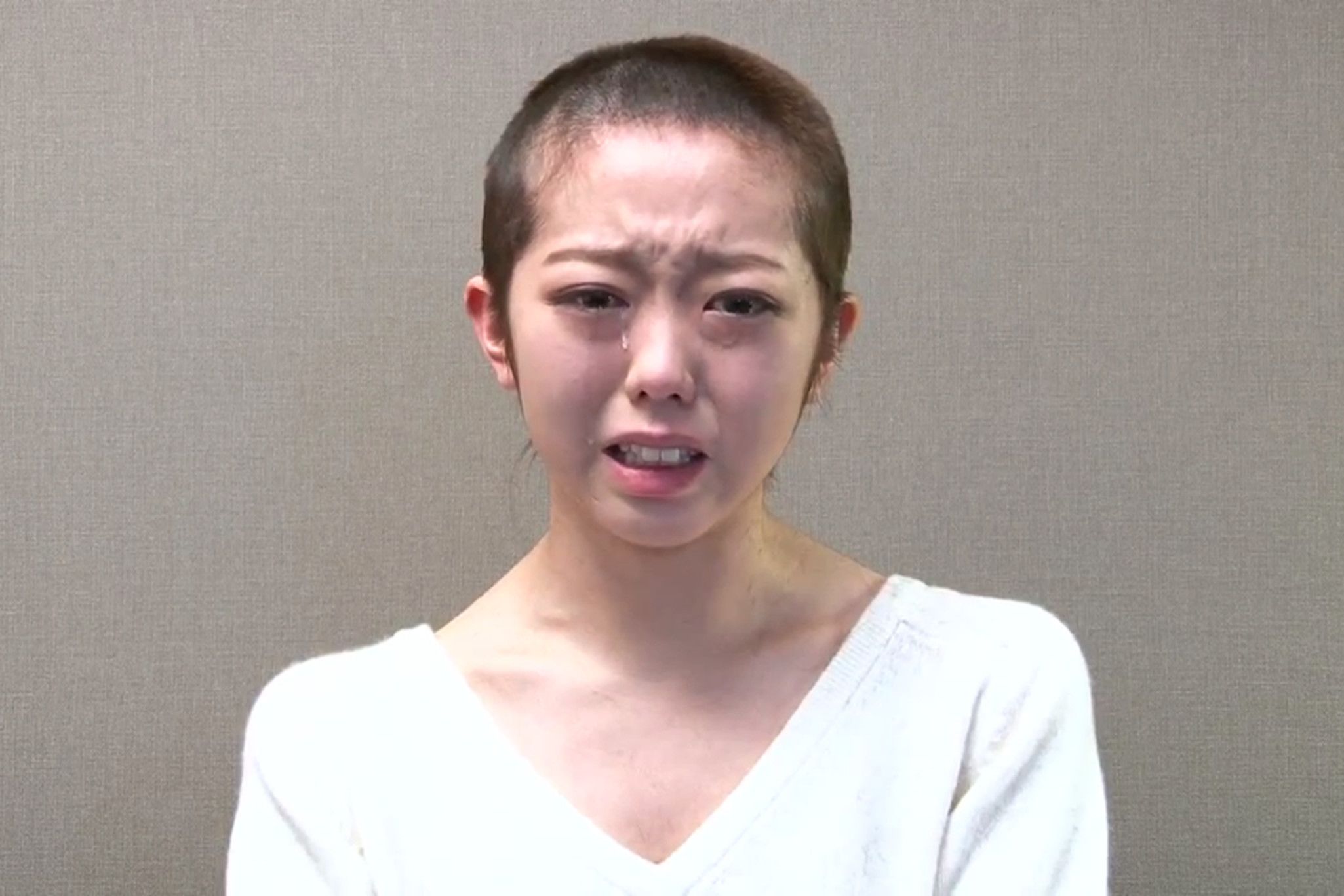

Popular member Atsuko Maeda tearfully announcing her graduation - video of this moment with English captions available below

Popular member Atsuko Maeda tearfully announcing her graduation - video of this moment with English captions available below

Maeda waving goodbye at her graduation concert

Maeda waving goodbye at her graduation concert

Graduations and Auditions

One aspect of the Japanese idol industry that tends to surprise foreigners the most is the graduation system. Much like a school, many female idol groups allow members to leave the group whenever they please with a ceremonious graduation. This is also a convenient way to remove members who have broken group rules or damaged the group’s carefully crafted image. To fill the empty spaces left by past members, auditions for new girls to join are held frequently. However, successful applicants are not necessarily the ones who hold the most skill, but rather the ones who display the most potential. For many fans, part of the appeal of AKB48 is the process of watching the members grow and learn as both performers and human beings. Hidetomi Tanaka, a professor at Jobu University, explained this concept to Reuters, saying that "These girls start from the amateur level with few singing and dancing skills, but the thing is they grow up with their fans." (Guardian). Rather than performing a contrived projection of permanence, AKB48 capitalizes on the inherently impermanent nature of its line-up, which harkens back to the traditional Japanese aesthetic value of wabi sabi. Andrew Juniper describes wabi sabi as an aesthetic which “embodies the Zen nihilist cosmic view and seeks beauty in the imperfections found as all things, in a constant state of flux, evolve from nothing and devolve back into nothing”(1). Wabi sabi is a highly complex and nuanced cultural value which is difficult to evaluate in a short piece of writing, but its general themes can be observed in many aspects of AKB48’s activities. By commercializing imperfection and impermanence, AKB48 incorporates the traditional Japanese aesthetic of wabi sabi into modern pop culture, thereby maintaining an aspect of historical Japanese identity in the modern era.

Sexualization

Sexualization

While the members of AKB48 range in age from pre-teens to late twenties, the typical fan is a man old enough to be the members’ father or even grandfather. Many older male fans describe their relationship to the group and its members as similar to that of uncles supporting their young nieces. A similar phenomenon can be observed in the Korean pop music industry; Yeran Kim, associate professor at Kwangwoon University’s School of Communications, claims that through the use of this title “the male’s gaze at young female bodies is legitimized and normalized as the voluntary support and pure love of uncles for their nieces...Thus, with the pretentious reformulation of the male gaze into an uncle’s familial support, the male consumption of girl bodies becomes relieved of the predictable blame for pedophiliac abnormality.” (340) The suggestion of a familial relationship between fans and idols is complicated by the often sexual nature of the group’s activities.

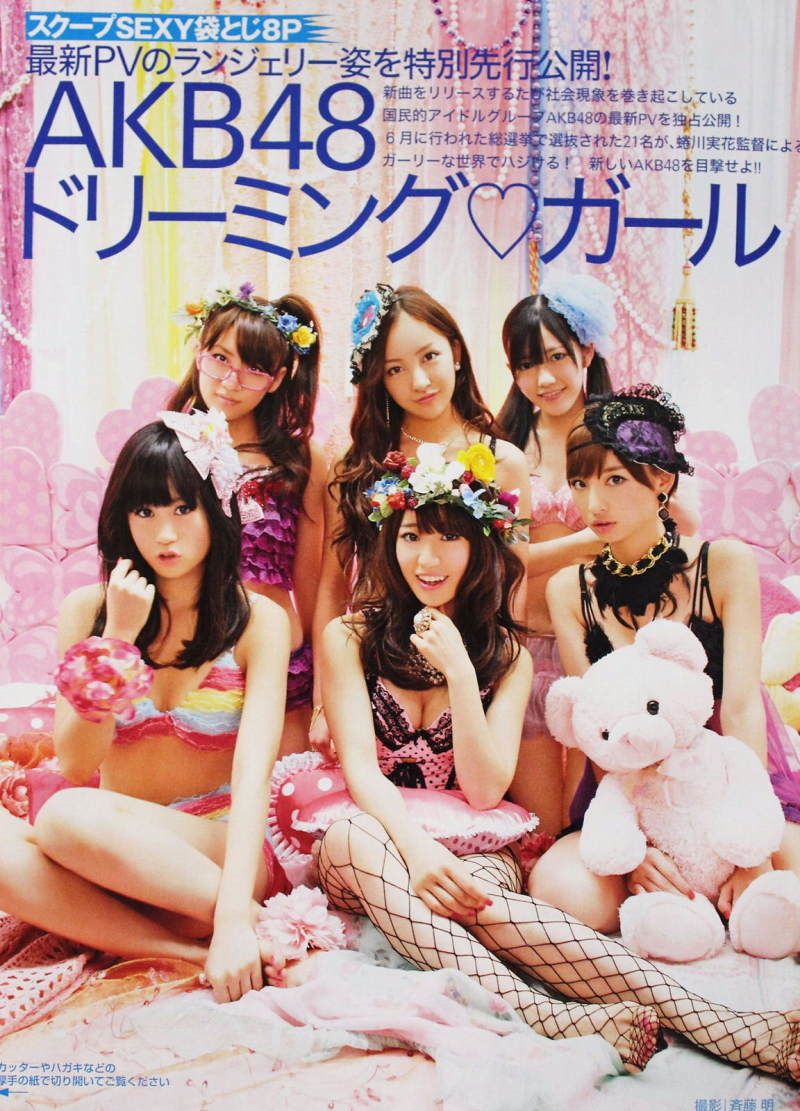

Many of AKB48’s summer-themed music videos portray the members dancing in bikinis on various beaches. The 2010 music video for “Ponytail to Shushu,” embedded on the right, teases audiences by suggesting the girls’ nudity in a school locker room but always blocking them behind moving objects. Another music video released the same year promoting the single “Heavy Rotation” went a step further by including scenes of many of the members wearing lingerie at a slumber party and occasionally kissing each other. Outside of their musical promotions, many members model in magazines or photobooks. Some of these photoshoots are obvious gravure as their wardrobes include the aforementioned bikinis, lingerie, and other revealing outfits. On the other hand, photoshoots that appear to be innocent may sexualize innocence itself. The Japanese school gym class swimsuit is modest, but photography that emphasizes the subject’s age by picturing her in such a swimsuit is anything but. Japanese girls and women struggle with sexual harassment and assault, leading to the creation of female-only subway trains where girls can commute to school without fear of being groped. Although most Japanese public schools have strict uniform rules such as minimum skirt length and required hairstyles, sexualization of the uniform prevails. AKB48’s uniform wearing blurs the lines between student and performer, school and sex, child and adult, and normalizes the overlapping of these distinctions in Japanese pop culture as a whole.

AKB48 members promoting "Heavy Rotation" for a magazine photoshoot

AKB48 members promoting "Heavy Rotation" for a magazine photoshoot

Then 14-year-old member Miki Nishino wearing a bikini.

Then 14-year-old member Miki Nishino wearing a bikini.

The Love Ban

The Love Ban

AKB48’s complicated relationship with feminine purity is not a new concept for female performers in Japan. In the 1600s, kabuki actresses were banned from performing due to allegations of widespread prostitution. Women have also been historically barred from participation in other traditional Japanese theatrical forms such as kyogen, bunraku, and noh. In the early 1900s, the all-female theatrical troupe entitled the Takarazuka Revue purposely distanced its performers from previous notions of impurity among actresses by labeling all active members as “students,” as well as referring to the performers who exclusively played female roles as musumeyaku (daughter role) rather than onnayaku (female role), as the former “connoted filial piety, youthfulness, pedigree, virginity, and an unmarried status” (Robertson 167). The importance of the unmarried status to the group’s image was such that members needed to graduate if they wished to marry. Despite the sexuality of AKB48’s performance, members face a similar policing of female sexuality that their Takarazuka counterparts first encountered over a century ago.

One of the most controversial aspects of AKB48’s design is the requirement that, in order to be an active member of the group, members must not ever be caught in a romantic or sexual context with a man. While other idol groups often implement similar rules, the popularity of AKB48 increases the scope of the scandals when a member transgresses. Arguably the most famous dating scandal in the history of J-pop was that of founding member of AKB48 Minami Minegishi. When a tabloid caught 20-year-old Minegishi at the home of a young male musician in 2013, she shaved her head and uploaded a video of herself tearfully apologizing onto YouTube. This scandal drew international attention and sparked debate among people in Japan. BBC news cites a fan on Twitter saying "What's the point of this public execution show? It's like something from the war or a totalitarian state" (AKB48 Pop Star Shaves Head after Breaking Band Rules). Others did not show Minegishi much pity; commenters on a Sponichi Annex article left sentiments including “Disgusting! She shaved her head out of self-satisfaction!!!”, “She’s the shame of Japan,” and “way too dramatic” (AKB峯岸みなみ). Minegishi’s actual punishment amounted to temporary demotion to the trainee level- she was eventually reinstated as a full-member and will soon graduate from the group. While her career continued, public criticism of the nature of her apology exemplified the pressure placed on members of the group.

Minami Minegishi is only one example of a love ban transgression within AKB48, and AKB48 is only one example of an idol group that upholds the love ban, albeit the most famous one. The prevalence of the ban among numerous idol groups has prompted research, discussion, and even legal action. A 2016 MaiNavi Student survey of 202 male college students in Japan found that 25.7% believed the love ban was necessary while the remaining 74.3% believed that it was not (マイナビ学生). The reasons surveyed individuals used to justify the ban included the protection of fans’ feelings, the duty of an idol to serve as a dream-like figure, and the distraction that a significant other could bring into an idol’s life. Those who opposed the love ban, on the other hand, asserted that the ability to date is a human right and that idols are entitled to personal freedom. If AKB48 continues to uphold this rule, they will continue to contribute to the historically-rooted purity culture of Japanese society. The discussion that the group brings to the topic suggests a potential for a shift in this culture, but evidence of such a shift in the court system is mixed. According to the Japan Times, the Tokyo District Court ruled that a former member of an unnamed idol group “should pay compensation for having a romance in defiance of the ban on dating imposed on many idol entertainers” in September of 2015, thereby siding with the talent agency’s ban. On the other hand, the same court “rejected a damage suit filed by a talent agency against [another] former member of an idol pop group” who committed a similar breach of contract by dating a fan. In the latter suit, Judge Katsuya Hara cited human rights concerns as reasoning for ruling in the former idol’s favor, claiming that a contractual ban on dating “significantly restricts the freedom to pursue happiness” (Japan Times). These legal conflicts reflect the discussions seen in internet comment sections and surveys, suggesting that methods balance between traditional cultural values and modern conceptualizations of freedom are actively being navigated in Japanese society as a result of the idol dating ban.

Minami Minegishi wearing a school uniform

Minami Minegishi wearing a school uniform

Minegishi's Tearful Apology

Minegishi's Tearful Apology

Western News Media

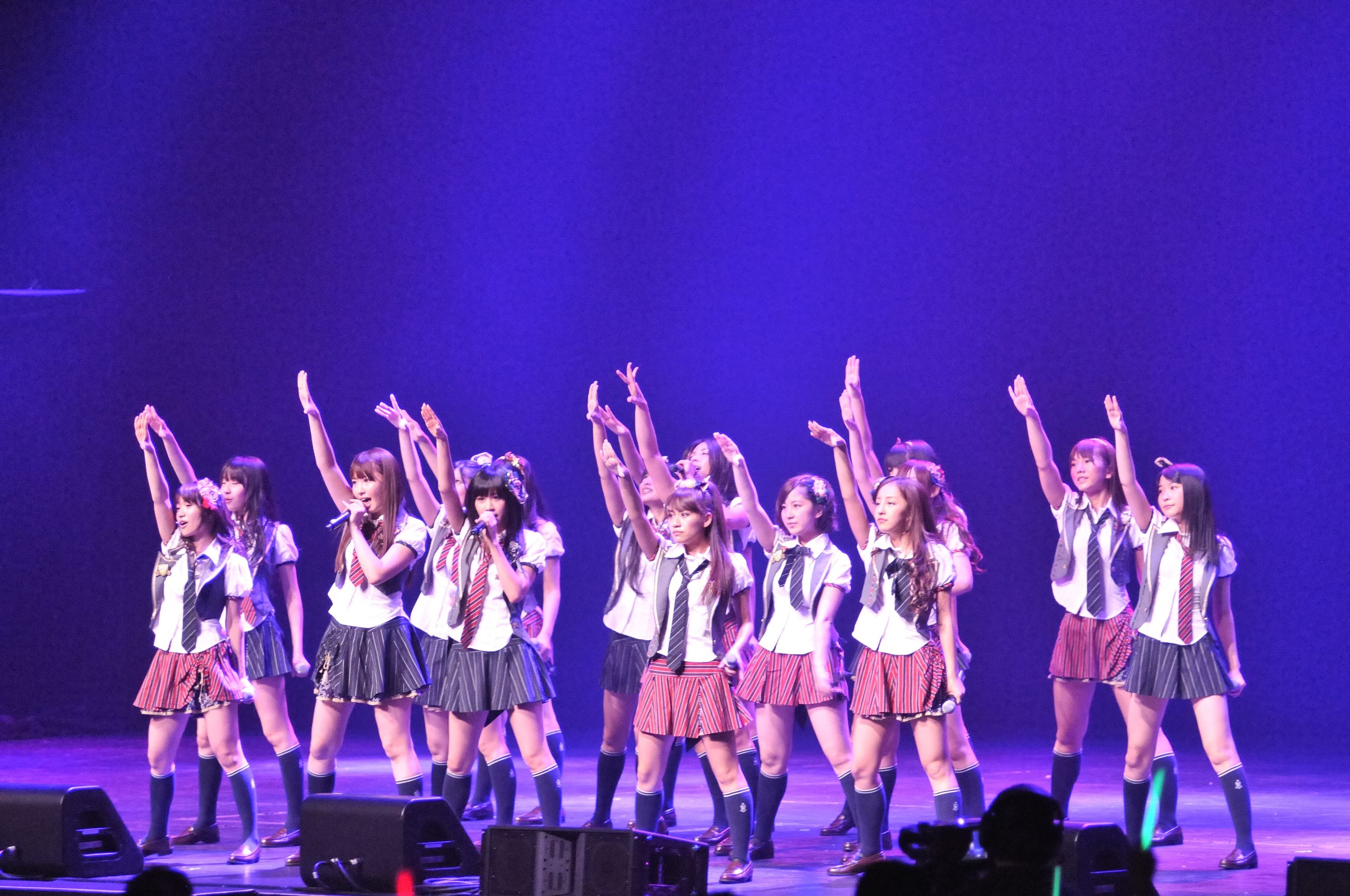

AKB48 Performing in the US during an anime convention, 2010

AKB48 Performing in the US during an anime convention, 2010

Members pictured in a school setting

Members pictured in a school setting

Western News Media

As I mentioned in the introduction, Koichi Iwabuchi claims that “Indifference, othering and antagonism” from international audiences toward Japan “might also be generated by the spread of Japanese media culture” (425). In the case of AKB48, the novelty of the group’s activities can easily be described through ethnocentric perspectives in a way which undermines their potential to spread pop cultural soft power. Joseph Nye asserts that “soft power rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others,” and therefore AKB48’s influence has the potential to be subverted by international media outlets (95). Nye goes on to say that “attention rather than information becomes the scarce resource” in a society with widespread access to information via the internet (99). Considering the likelihood that most western audiences do not speak Japanese, English-speaking journalists possess the power to redirect attention to certain aspects of AKB48’s activities and construct their own narratives. In this section, I will examine cultural antagonism as expressed through news articles published in a few major English-language news websites- CNN, The Atlantic, and The Independent.

The first common trend I observed among these articles was the use of militaristic language to explain the concept of AKB48. In CNN’s account of Minami Minegishi’s head-shaving scandal, author Peter Shadbolt described Minegishi as a “disgraced samurai” who broke the group’s “‘no-romance’ bushido.” These language choices are rooted in history dating back to the feudal era of Japan. By referencing the samurai, or feudal military nobility, and bushido, the code of honor that the samurai followed, Shadbolt draws a connection between a present-day twenty-year-old woman and ancient warriors. While these references acknowledge potential historical cultural influences which may have led to the formation of modern idol culture, they do not provide any further explanation. Shadbolt goes on to refer to AKB48 as a whole as “J-pop’s standing army,” claiming that “The bubblegum empire even has foreign territorial ambitions.” These militaristic metaphors are a sensationalist tactic which bring the reader forward in history to the era of the Second World War, a time which many in the English-speaking world already have strong associations with and emotions related to. However, Japan has not had a true army since the United States formulated their current constitution; the country does not hold the imperial power it once did, nor does it have any immediate foreign territorial ambitions. The author creates a narrative that soft power cultural exports are somehow equivalent to true military power and frames the young women of AKB48 as the aggressors. Other news organizations utilize similar language- name here of the Independent accused AKB48’s producer of “trying to export his empire abroad,” and David McNeill of The Atlantic titled his article “The 48 Japanese Schoolgirls Aiming to Take Over the World.” These language choices suggest that a prevailing association of present-day Japan with World War II-era Japan exists in western cultures. The application of these ideas to AKB48 also suggests that the group may not have the power to influence these interpretations or change them in Japan’s favor.

In addition, some of these articles’ descriptions of AKB48 border on insulting the group, its members, and its fans. Patrick St. Michel of The Atlantic describes their music as “unremarkable” and “the worst tendencies of Europop fused with dinner-theater cheesiness.” This opinion is fair enough in itself, but the article does not consider the possibility that some people do enjoy AKB48’s music or that their music could contribute to their commercial success. He also refers to the members as “48 adult women dressed as school girls,” which is simply not true, as a large percentage of the members are actually middle- and high-school students. The Independent cites Tokyo-based music journalist Steve McClure, who states that “Their music, with its emphasis on group vocals and lack of harmony, ironically reflects the premium placed on group harmony and non-threatening mediocrity by Japanese society and the mass media.” This brief statement makes an overarching claim about Japanese society as a whole without any elaboration within a non-academic context, thereby oversimplifying Japanese culture to an audience who may not care to or have the ability to critically analyze the assertion. Again, AKB48’s potential soft power is subverted by the journalists through which information about the group is filtered. In addition, these statements contain negative implications for Japanese culture as a whole, potentially resulting in AKB48 having a negative impact on western interpretations of Japanese identity.

Influence Throughout Asia

Influence Throughout Asia

The United States is not unique in its complicated history with Japan; many other countries, especially those located in East and Southeast Asia, have seen great suffering due to the actions of the Japanese imperial army. In fact, the negative feelings harbored toward Japan within these countries often exceeds those felt in the English-speaking world. However, Japanese pop culture exports appear to be largely accepted by modern populations in these regions. Nissim Kadosh Otmazgin, East Asian Studies lecturer and research fellow at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, notes that “Although people in East Asia today may not be completely ignorant of Japan’s past wrongdoing and might still be critical of the Japanese government,” Japanese pop culture exports such as anime, manga, and music are readily consumed in locations such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Taiwan, causing young people living there “to associate Japan as home to a dynamic and prosperous cultural industry, rather than just an industrial superpower or an ex-military aggressor” (3). This increase in positive feelings toward Japan exemplifies the potential for pop culture exports to increase Japan’s soft power, and AKB48 is one such export.

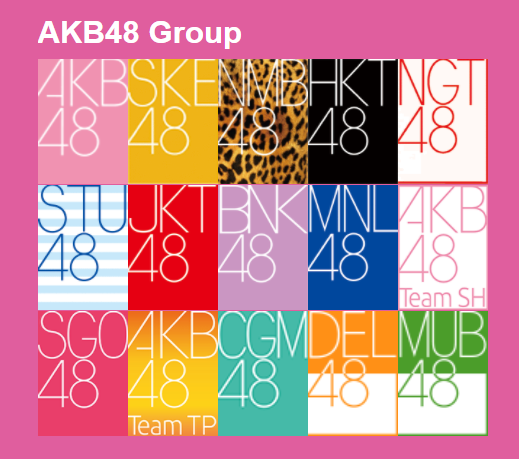

Aside from the flagship group and Japanese sister groups, AKB48 has many international sister groups which are either currently active or in the process of beginning activities (likely what Peter Shadbolt was referring to in his mention of “foreign territorial ambitions”). The groups include JKT48 (Jakarta, Indonesia), BNK48 (Bangkok, Thailand), MNL48 (Manila, Philippines), AKB48 Team SH (Shanghai, China), SGO48 (“Saigon 48,” Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam), AKB48 Team TP (Taipei, Taiwan), CGM48 (Chiang Mai, Thailand), DEL48 (Delhi, India), and MUB48 (Mumbai, India). The members of these groups are typically native to the countries in which they are active, and songs are recorded in the native language of each respective group. However, the links to Japan and to the flagship group are continuously emphasized in each group’s activities. The international sister groups do not typically produce original music, but rather re-record original AKB48 songs in their own languages, often still including references to the original Japanese lyrics. DEL48’s website immediately opens with the statement “DEL48 is the sister group of the Japanese idol AKB48,” suggesting no desire to distance themselves from the flagship. In addition, JKT48’s 2012 joint concert with AKB48 in Jakarta was sponsored by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy of Indonesia, displaying desire from the governments of both countries to foster friendly cross-cultural relationships (Burhani).

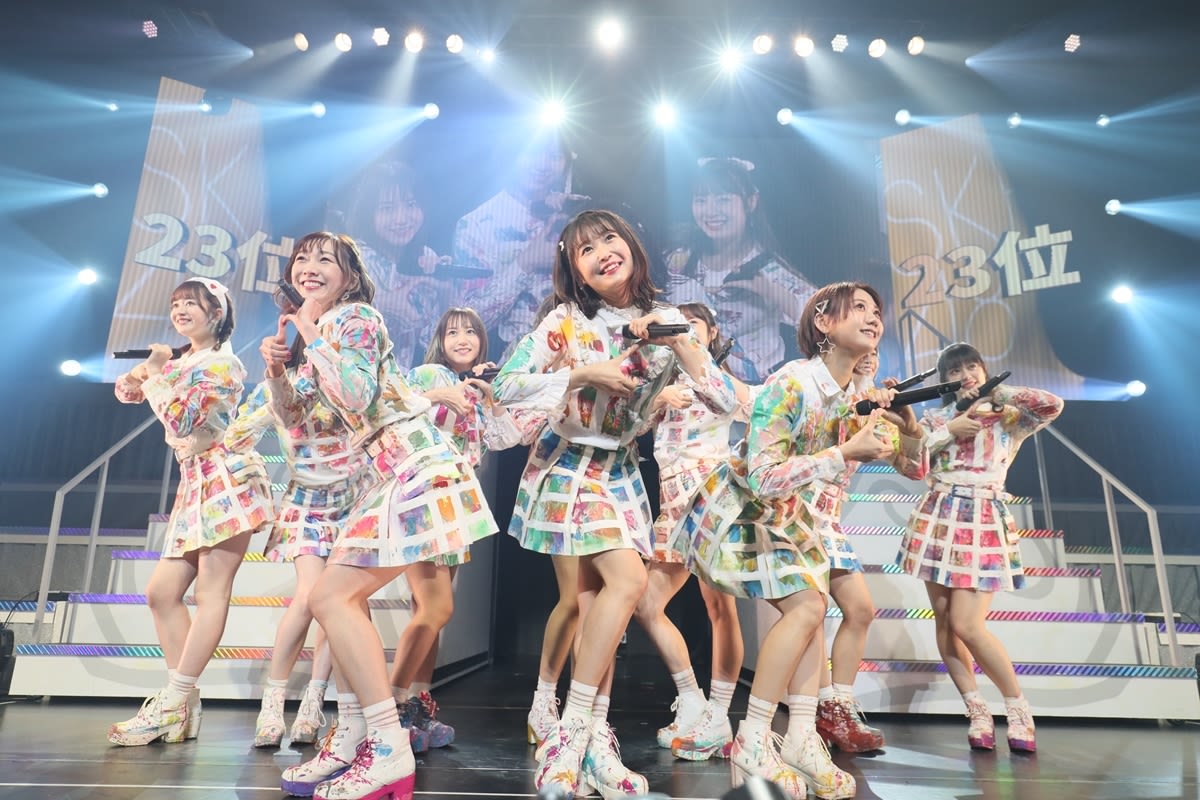

On January 27, 2019, AKB48 held its first concert event involving 76 members from seven sister groups in Bangkok entitled “AKB48 Group Asia Festival 2019.” During the concert, AKB48 veteran Yui Yokoyama made a speech in which she said “We all came from different regions with different cultures and activities, but I believe we are on one team” (MNL48 Philippines). MNL48’s official website claims that the event was very successful and therefore will be followed by more international crossover events in the future. Nissim Kadosh Otmazgin claims that these sorts of activities “might build new circles of allegiance” among individuals from different cultures (16), so perhaps the cooperation between AKB48 and its overseas counterparts will result in the formation of more positive relationships between individuals from their respective countries in the future.

Logos of all sister groups as displayed on AKB48's official website

Logos of all sister groups as displayed on AKB48's official website

BNK48 promoting their adaptation of AKB48's song "Heavy Rotation," with the Japanese transliteration of the title written beneath the English

BNK48 promoting their adaptation of AKB48's song "Heavy Rotation," with the Japanese transliteration of the title written beneath the English

JKT48's Indonesian adaptation of "Heavy Rotation"

Members of seven AKB48 groups performing together during the 2019 AKB48 Group Asia Festival in Bangkok

Members of seven AKB48 groups performing together during the 2019 AKB48 Group Asia Festival in Bangkok

Conclusion

Conclusion

The growing accessibility of mass media pop culture exports to global audiences has had a powerful impact on Japanese cultural diplomacy, and that impact will likely continue to evolve with the evolution of information technology. AKB48’s role in this cultural diplomacy is just as complex as the social, historical, and cultural factors that influence the group and the countries it interacts with. Within Japan, the group’s activities contribute to domestic conceptualizations of Japanese identity by fostering democracy and applying traditional Japanese cultural values such as wabi sabi, purity, and duty to modern culture while also creating new opportunities to discuss and debate these values. In the west, negative depictions of AKB48 are indicative of historical wounds not yet healed. In other Asian countries, however, the success of AKB48’s sister groups presents a positive outlook on the future of relations between present-day Japan and countries that have been victimized by Japan in the past. This wide variety in domestic and international cultural impact is significant in its implication that even single entertainment groups or companies can have widespread influence on global understandings of a country’s culture and people. As internet accessibility continues to spread throughout the world, international government organizations would likely benefit from working towards a more detailed understanding of the power of pop culture diplomacy to both positively or negatively influence intercultural relations. In the meantime, AKB48 and its sister groups show no signs of stopping their influential activities, and therefore display the potential to shape Japanese cultural relations for years to come.

Works Cited

AKB48 Pop Star Shaves Head after Breaking Band Rules. 1 Feb. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-21299324.

“AKB48のランキング.” Oricon.co.jp, www.oricon.co.jp/prof/385015/rank/.

“AKB峯岸みなみ、ウィッグ初脱ぎ「両親の涙、一番つらかった」 - スポニチ Sponichi Annex 芸能.” スポニチ Sponichi Annex, スポニチ Annex, 20 Nov. 2016, www.sponichi.co.jp/entertainment/news/2013/04/22/kiji/K20130422005663870.html.

Burhani, Ruslan "AKB48 dan JKT48 akan tampil di Jakarta." . Antara News, 14 February 2012.

“Court Rules Pop Idol Has Right to Pursue Happiness, Can Date.” The Japan Times, 19 Jan. 2016,www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/01/19/national/pop-idol-right-pursue-happiness-not-liable-damages-breach-dating-ban-court/.

DEL48 Official Website. www.del48.com/.

Iwabuchi, Koichi.“Pop-culture diplomacy in Japan: soft power, nation branding, and the question of ‘international cultural exchange’.” International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 21, no. 4, 2015, pp. 419-432.

Juniper, Andrew, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence. Tuttle Publication, 2011.

Kim, Yeran. “Idol Republic: the Global Emergence of Girl Industries and the Commercialization of Girl Bodies.” Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, Dec. 2011, pp. 333–345.

Kiuchi, Yuya. “Idols You Can Meet: AKB48 and a New Trend in Japan’s Music Industry.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 50, no. 1, 2017, pp. 30–49.

McCurry, Justin. “Japan gripped by TV election of pop group AKB48.” The Guardian, 8 June 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jun/08/japan-election-pop-group-akb48.

McNeill, David. 2014. “Meet AKB48: Pop, sex and schoolgirl schtick make for controversial success.” The Independent, July 14. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/meet-akb48-pop-sex-and-schoolgirl-schtick-make-controversial-success-9603720.html

MNL48 Philippines. AKB48 Group Asia Festival 2019 in Bangkok Presented by Shanda Games. 31 Jan. 2019, mnl48.ph/news-and-updates/akb48-group-asia-festival-2019-in-bangkok-presented-by-shanda-games/.

Nye, Joseph. “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 616, 2008, pp. 94-109.

Otmazgin, Nissim Kadosh. “Japan Imagined: Popular Culture, Soft Power, and Japan’s Changing Image in Northeast and Southeast Asia.” Contemporary Japan, vol. 24, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–19. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ant&AN=XRAI12O07Z-847&site=ehost-live.

Robertson, Jennifer. Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture In Modern Japan. E-book, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008, https://hdl-handle-net.proxy.binghamton.edu/2027/heb.94082.

Shadbolt, Peter. 2013. “When a teen pop star breaks J-pop ‘bushido’ code.” CNN, February 4. https://www.cnn.com/2013/02/04/world/asia/japan-akb48/index.html

Smith, Hanscom. “Toward a Universal Japan: Taking a Harder Look at Japanese Soft Power.” Asia Policy, vol. 15, 2013, pp. 115-126.

St. Michel, Patrick. 2011. “The 48 Japanese Schoolgirls Aiming to Take Over the World.” Atlantic: Web Edition, October 18. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.binghamton.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/149A572D24AE1F18.

マイナビ学生 . “女性アイドルの「恋愛禁止ルール」ってあったほうがいい? なくてもいい? 男子大学生に聞いてみた.” ニコニコニュース, ニコニコニュース, 24 August 2016, news.nicovideo.jp/watch/nw2357380.

Mediography

“AKB48 Full Group Photo.” Stage48, 2017, stage48.net/wiki/images/thumb/d/d8/AKB48Nov2017.jpg/800px-AKB48Nov2017.jpg.

“AKB48 Promoting 10nen Zakura.” AKB48 Fandom, akb48.fandom.com/wiki/10nen_Zakura.

“All Sister Groups Screenshot.” AKB48公式サイト, www.akb48.co.jp/.

Amith, Dennis. “AKB48 US Performance.” Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/kndynt2099/5767061564/sizes/o/in/photostream/.

Baron, Karl. “AKB48 Theater in Akihabara, Tokyo.” Wikipedia, 29 Apr. 2010, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AKB48#/media/File:AKB48_theater.jpg.

“Everyday、カチューシャ 【Original Edition Type-A】.” Hello! Online, 4 Oct. 2011, www.hello-online.org/index.php?app=picapp&CODE=comments&picture=202362.

Girls on Stage with Microphone Stand in Center. 31 Jan. 2019, mnl48.ph/news-and-updates/akb48-group-asia-festival-2019-in-bangkok-presented-by-shanda-games/. Accessed 2020.

“Heavy Rotation Magazine Photoshoot.” Amazon, 2014, www.amazon.com/Playboy-Japanese-Magazine-December-JAPANESE/dp/B00ORW4U1M.

“Jurina Matsui Celebrating Her Ranking.” Sponichi Annex, 14 Mar. 2019, www.sponichi.co.jp/entertainment/news/2019/03/14/gazo/20190314s00041000072000p.html.

“Large Group Bikini on Beach.” Tokyo Girls' Update, tokyogirlsupdate.com/profile/akb48.

“Maeda Atsuko's Graduation in Tokyo Dome.” Stage48, 2012, stage48.net/wiki/index.php/Maeda_Atsuko.

“Miki Nishino Swimsuit.” Fanpop, zh.fanpop.com/clubs/akb48/images/37401171/title/akb48-sousenkyo-swimsuit-surprise-2014-photo.

“Minami Minegishi Apology.” BBC News, 1 Feb. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-21299324.

“Minami Minegishi School Uniform.” Stage48, stage48.net/wiki/index.php/Minegishi_Minami.

“Rino Sashihara in Cape.” 音楽Natalie, 7 June 2014, natalie.mu/music/news/118455.

“Seven Members in Bikinis.” 48 Group West, 20 May 2020, 48gwest.com/2020/05/02/48group-summer-bikini-singles-part-1/.

“Yuko Oshima Magazine.” Ameblo, 20 Aug. 2009, ameblo.jp/harumagedon2012/entry-10324982367.html.

“『第6回AKB48選抜総選挙』2位の指原莉乃.” Oricon Music, AKS, www.oricon.co.jp/news/2038346/photo/2/.

“【1 / 13】AKB48山内瑞葵、新曲センター抜てきに涙「震えが止まらない」.” マイナビニュース, news.mynavi.jp/photo/article/20200120-957337/images/001l.jpg.

“前田敦子(左)演唱會宣布卒業,同時進入AKB的隊長高橋南(右)安慰。(圖/截自網路).” Yahoo News, 21 May 2012.