Culture of Bias Against Female Foreign Domestic Workers in Hong Kong: An Analysis on the Relationship Between Media and Policy.

Sophie Tadelis

Introduction

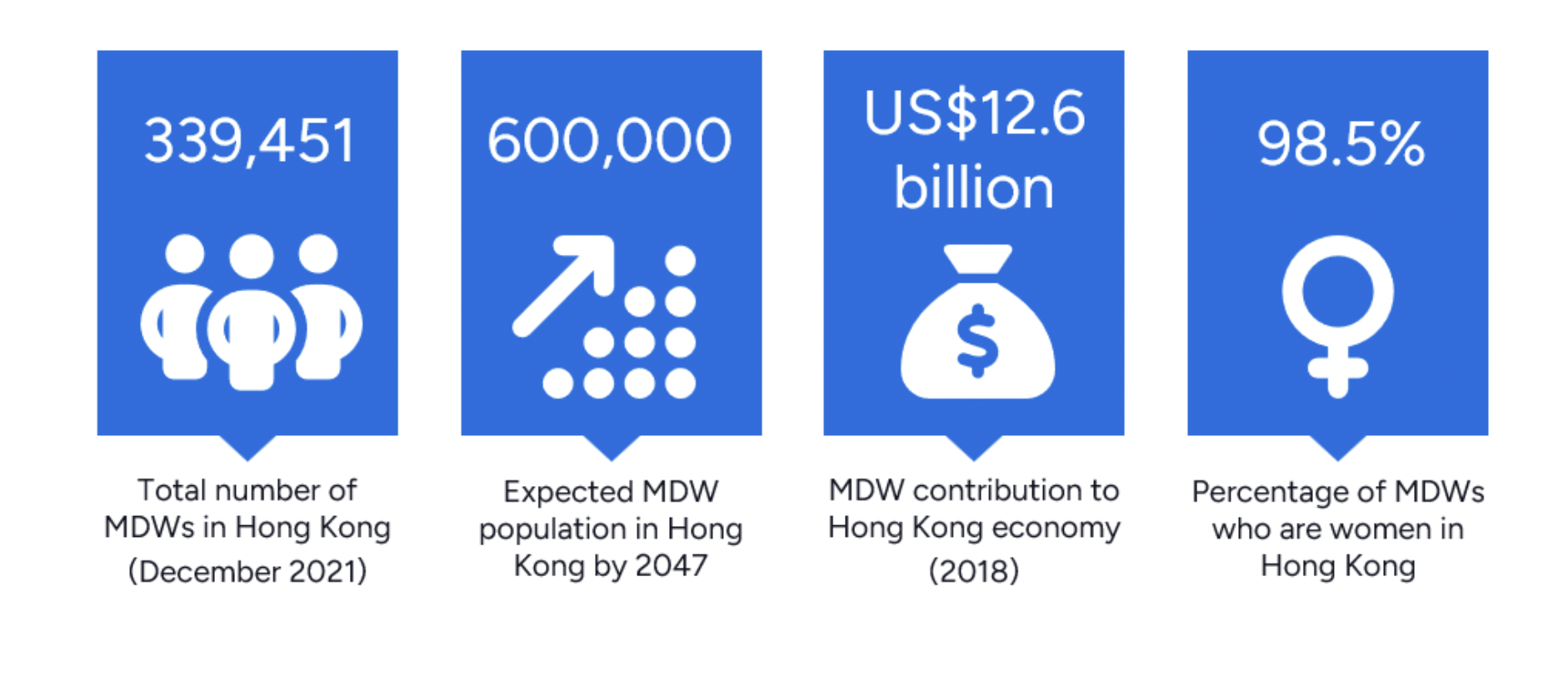

What are Foreign Domestic Workers? (making infographic)

“She was a domestic worker. She came here to work. She did not deserve this death.” (Asian Migrants’ Coordinating Body [AMCB], 2024). The AMCB spokesperson’s words echo across a city where over 400,000 female foreign domestic workers live and work in the shadows of one of Asia’s wealthiest metropolises. In October 2024, the murder of a domestic worker by a white, wealthy British expatriate at Pok Fu Lam’s waterfalls - a scenic public space frequented by Hong Kong’s (HK) elite - forced the city to yet again confront an uncomfortable truth: the vulnerability of its foreign domestic worker population is not just a matter of individual tragedy, but a reflection of deeply rooted systemic failures.

The media coverage that followed revealed more than just the details of a horrific crime. It exposed the stark contrasts in how Hong Kong’s press portrays its foreign domestic workers (FDW). When they are victims versus accused, when they are demanding rights versus providing service, when they are humans versus statistics. In a city where local newspapers regularly highlight crimes committed by domestic workers while minimizing their victimization, this case became a rare moment where the longstanding narrative shifted, if only momentarily. Yet even in this coverage, familiar patterns emerged. While international media emphasized the victim’s humanity, local reporting often focused on the perpetrator’s status and background, relegating the domestic worker to a secondary character in her own story. This dichotomy exemplifies the complex interplay between media representation, policy enforcement, and societal attitudes that continue to shape the lives of hundreds of thousands of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong.

This case and many others alike illuminate a critical question about the relationship between media representation and systemic discrimination in Hong Kong .

This capstone’s main focus is centered around Hong Kong’s media, policy and legal cases involving the treatment of female FDWs. Using various frameworks, such as narrative/framing theory, feminist theory, and political trends/theory, this paper will demonstrate how the media and public policy within Hong Kong reinforce each other to produce and sustain a culture of pervasiveness and harmful biases against female FDWs, who make up an overwhelming 98.5% of all FDW in Hong Kong. The murder, and its current unwinding aftermath, suggest how the interplay between media portrayal and policy-making creates a self-reinforcing cycle that perpetuates discrimination against female foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong, while simultaneously shaping public perception and institutional responses to their struggles.

Research Questions

How do press-based media portrayals of foreign domestic workers influence policy decisions and reinforce systemic discrimination?

What are the cyclical effects of these representations on societal attitudes and institutional practices in Hong Kong?

Empowering voices: A domestic worker leads a protest in Hong Kong advocating for equal rights and fair treatment.

Empowering voices: A domestic worker leads a protest in Hong Kong advocating for equal rights and fair treatment.

Statistics highlighting the role of migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong's workforce and economy

Statistics highlighting the role of migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong's workforce and economy

FDW attending protest. Image courtesy of South China Morning Post. Retrieved from South China Morning Post.

FDW attending protest. Image courtesy of South China Morning Post. Retrieved from South China Morning Post.

Theoretical Framework: To successfully explore the complex interplay between journalistic media, policies, and their role in fostering and perpetuating a unique cultural framework in Hong Kong, it is essential to utilize sociological and anthropological theories, including those on framing, intersectionality, and policy myopia.

Framing

Framing, as conceptualized by Gamson (1996), is not merely a top-down imposition of narratives by political elites but a dynamic, discursive process where language, symbols, and prevailing societal norms combine to legitimize particular ideologies within physical and symbolic spaces.This framing process involves strategic actors, including media, policymakers, and marginalized communities, utilizing symbolic and material resources to collectively interpret and influence policy and societal issues (Pan & Kosicki, 1997; Gamson & Modigliani, 1989). The media acts as both facilitators and participants, shaping narratives while creating spaces for public discourse that enable interactions between the public and elites. This collaboration influences the production of frames, albeit often embedded with systemic biases and personal prejudices.As Chan (2009) highlights, media does not merely report on policies but actively shapes them through a reciprocal relationship with policymakers. Media coverage can amplify public sentiment, creating pressure on policymakers to align their decisions with dominant narratives. This is particularly evident in issues concerning foreign domestic workers (FDWs), where media frames often emphasize economic utility or moral failings, guiding policy responses that reflect and perpetuate these portrayals. The dynamic two-way interaction between media and policymakers ensures that these narratives are not only maintained but reinforced, embedding systemic biases into Hong Kong’s sociopolitical landscape. Importantly, this process is not uniform or unidirectional. Various groups, including foreign domestic workers themselves, actively engage with, and sometimes resist, dominant narratives, demonstrating agency in how their stories are told and understood. For instance, while some narratives might emphasize vulnerability or victimhood, others highlight economic empowerment and strategic decision-making - as exemplified by workers who successfully support their families while navigating Hong Kong's complex social landscape. This relationship between media, policy, and public discourse creates what might be called a cultural feedback loop. While media outlets and political elites often initiate certain narratives, these frameworks are continuously negotiated, challenged, and transformed through public engagement (Gamson, 1992; Pan & Kosicki, 1997). Rather than viewing media framing as a simple tool of oppression or empowerment, we might better understand it as a contested space where various actors - including domestic workers, employers, advocacy groups, and policymakers - negotiate meaning and influence outcomes. Chan (2009) further illustrates how media framing functions within a cultural feedback loop, where dominant narratives shape public attitudes, and these attitudes, in turn, influence media and policy frameworks. For FDWs in Hong Kong, this feedback loop sustains a culture of bias, as media often portrays them as either victims requiring strict regulation or as contributors to social problems. These frames not only inform public perception but also legitimize policy decisions that fail to address the complex realities of FDWs’ lives, reinforcing cycles of discrimination. This complexity suggests that examining media framing requires careful attention to multiple perspectives and competing interests, acknowledging that beneficial and exploitative elements often coexist within the same system. Such an understanding allows us to recognize both structural constraints and individual agency, emphasizing that multiple truths can coexist within these complex social dynamics. This theoretical framework provides the foundation for analyzing how media representations and policy decisions in Hong Kong mutually reinforce and challenge existing power structures while shaping public discourse about foreign domestic workers. Framing not only dictates the narrative of a certain issue but further frames social groups as well, the framers are in a sense being framed

Intersectionality

Within Hong Kong’s sociocultural landscape, foreign domestic workers’ identity markers and categorizations bear a complex and nuanced history, with profound implications for both institutional structures and interpersonal dynamics. These markers, encompassing nationality, gender, class, migration status, and economic position, fundamentally shape their lived experiences and social positioning within Hong Kong society. To understand these intersecting dimensions of identity and oppression, we turn to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality, developed in her seminal 1989 work. Crenshaw’s framework provides crucial insights for understanding how multiple identity markers intersect and operate within any given mainstream culture, particularly relevant when examining the experiences and the current perceptions of FDWs in Hong Kong. She analogizes identity to a traffic intersection, where various aspects such as race, gender, class, and migration status converge, aptly capturing the complex dynamics these women navigate daily. This intersection of identities creates unique vulnerabilities and challenges that cannot be understood by examining any single aspect in isolation.The application of intersectional praxis, the practical implementation of intersectionality theory, reveals how discrimination against foreign domestic workers stems from the intricate interconnections of various axes of oppression. For instance, their experiences are shaped not merely by their status as foreigners or as women, but by the compound effect of being foreign women working in domestic labor, often from Southeast Asian countries, and typically from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. These overlapping identities interact with Hong Kong’s legal frameworks, social hierarchies, and cultural attitudes to create distinct patterns of marginalization and resistance.This theoretical framework becomes particularly valuable when analyzing how media representations and policy decisions interact with these various forms of oppression. Media frames often reflect and reinforce existing power dynamics, sometimes portraying foreign domestic workers as either helpless victims or over eager economic opportunists, rarely capturing the complexity of their lived experiences. Similarly, policies that appear neutral on the surface often have discriminatory impacts when viewed through both an intersectional and framing lens, revealing how different aspects of identity compound to create unique barriers and challenges.The recognition of intersectionality in the context of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong is paramount for understanding and addressing their multifaceted challenges. This includes examining how gender-based discrimination intersects with xenophobia, misogyny class prejudice, and labor exploitation. Moreover, intersectionality helps illuminate how these workers exercise agency and resistance within constraining structures, challenging oversimplified narratives of victimhood while acknowledging genuine structural obstacles. This theoretical approach thus provides a more nuanced framework for analyzing how multiple systems of oppression and privilege interact with media representation and policy formation. It reveals deeper power imbalances while acknowledging the complexity of individual experiences and forms of resistance within these systems. Such an analysis helps avoid reductionist narratives while recognizing how various forms of marginalization can simultaneously operate and reinforce each other within Hong Kong’s sociopolitical landscape.

Policy Myopia

Building on the insights provided by framing and intersectionality, it becomes evident that policy development and implementation often rely on reductive narratives that overlook the complexities of intersecting identities and systemic inequalities. This shortsightedness, commonly referred to as policy myopia, prioritizes immediate political or economic gains while disregarding the long-term structural changes needed to address entrenched inequities. For foreign domestic workers, this myopic approach exacerbates existing marginalization, as policies fail to account for their nuanced realities. Examining policy myopia as a framework enables a deeper understanding of how such governance practices not only reinforce systemic injustices but also hinder meaningful progress toward equity and inclusion. It is crucial to note that once policies are implemented, media influence diminishes, solidifying biases that were embedded during earlier framing stages (discourse, history etc.). This rigidity, coupled with media-driven narratives, limits the adaptability of policies affecting FDWs, perpetuating systemic inequalities contributing to the failure of myopic policies. One of the key drivers of policy myopia is bounded rationality, which restricts policymakers’ ability to account for the complexity and interconnectedness of social issues. Policymakers may adopt overly simplistic solutions or disregard structural inequalities that require nuanced, long-term strategies (Nair & Howlett, 2017). For example, immigration and labor policies affecting FDWs often focus narrowly on regulatory compliance or economic contributions, neglecting the intersection of race, gender, and class dynamics that shape these workers’ vulnerabilities. This reductionist approach perpetuates cycles of marginalization by failing to address the broader cultural and structural forces that maintain these inequities. Moreover, the rigid nature of myopic policies undermines their adaptability to evolving societal contexts. As Nair and Howlett explain, myopic policies are often designed with a static understanding of current conditions, rendering them ineffective as circumstances change. The rhetoric embedded within myopic policies not only reflects existing biases but also actively contributes to framing narratives that perpetuate a culture of discrimination against FDWs. These policies often emphasize the economic utility or regulatory compliance of FDWs while neglecting their social and human dimensions, reinforcing stereotypes that frame them as disposable labor or helpless victims. Such representations are mirrored in media narratives and societal attitudes, constructing a biased cultural framework that normalizes their marginalization.The very existence of these policies creates a structural environment where exploitation becomes more likely. Building on this, Chan demonstrates that media-driven narratives not only reflect public sentiment but actively shape policy priorities, creating a cyclical relationship between representation and governance. For FDWs, this manifests in policies that emphasize regulatory compliance over their human and social dimensions, perpetuating stereotypes that frame them as disposable labor. These policies, supported by media frames, construct an environment where exploitation becomes normalized, further marginalizing FDWs within Hong Kong’s sociocultural framework.

Combined Application

These theoretical frameworks, framing, intersectionality, and policy myopia, offer an integrated perspective for analyzing the intricate dynamics that define the experiences of FDW in Hong Kong. Framing theory sheds light on how media narratives and public discourse influence societal perceptions and reinforce power imbalances. Intersectionality underscores the layered nature of discrimination, revealing how overlapping identities such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status compound oppression. Policy myopia highlights the shortcomings of governance systems that prioritize simplistic, short-term solutions, often exacerbating systemic inequities. When applied in tandem, these frameworks provide a nuanced understanding of how media portrayals, legal frameworks, and cultural norms intertwine to shape not only the realities of foreign domestic workers but also the broader social fabric of Hong Kong

Media Representation

The representation of FDWs in Hong Kong’s Chinese-language media reveals entrenched patterns of misrepresentation, rooted in both historical narratives and contemporary biases. Historically, the roles of muijai (young female servants) and amahs (refugees working as domestic helpers) shaped a cultural framework that treated domestic workers as property rather than as individuals with agency. These roles, established during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, cemented a view of domestic labor as low-status and subordinated, with employers wielding near-total control. Although Hong Kong’s economy has evolved significantly since then, this historical commodification continues to influence perceptions of FDWs, portraying them as possessions that reflect the employer’s wealth and status rather than as autonomous workers deserving of rights and respect.In contemporary media narratives, these historical biases manifest through pervasive dehumanization of FDWs. Ho and Sewell (2023) identify a pattern of “perpetrator exoneration” and “victim blaming” in media coverage. Employers who mistreat or abuse FDWs are often portrayed sympathetically, with narratives emphasizing their personal stresses or emotional struggles. For example, cases of physical abuse are frequently framed around the employer’s difficulties, such as workplace pressures or stressful family obligations, while omitting or downplaying the severity of the abuse suffered by the FDWs. Conversely, FDWs are often reduced to negative stereotypes, described as “lazy,” “untrustworthy,” or “cunning,” effectively blaming them for their victimization. These portrayals diminish public empathy for FDWs, casting them as the cause of their own mistreatment rather than as victims of systemic exploitation.Sensationalism in media further distorts the representation of FDWs, particularly in cases of sexual violence. Reports often emphasize irrelevant details such as the worker’s physical appearance, youth, or presumed attractiveness, which are framed as factors that “provoked” the assault. These sensationalized narratives perpetuate harmful stereotypes, trivialize the severity of the violence, and reinforce myths that undermine the dignity of FDWs. For instance, reports describing victims as “beautiful” or “naive” not only feed into voyeuristic curiosity but also obscure the structural conditions that make such abuse possible, shifting attention away from systemic issues and onto superficial victim blaming esc characteristics.

Now Back to our Theories

These media narratives have profound implications for public perception and policy. By portraying FDWs as inherently problematic or morally suspect, the media fosters a culture of distrust that influences how society views this vulnerable group. Public acceptance of restrictive and exploitative policies, such as the live-in rule and the two-week rule, is bolstered by these narratives, which cast FDWs as a threat to social harmony or as individuals undeserving of empathy. In this way, the media does not merely reflect societal biases but actively perpetuates them, reinforcing the structural inequalities that trap FDWs in cycles of vulnerability and exploitation.Challenging these misrepresentations requires concerted efforts to foreground the humanity and dignity of FDWs in media coverage. Reframing narratives to highlight their agency, contributions, and rights can counteract the dehumanizing portrayals that dominate public discourse. By shifting the focus from employer-centered narratives to the systemic barriers faced by FDWs, media and society can begin to address the structural inequalities that sustain their marginalization in Hong Kong.

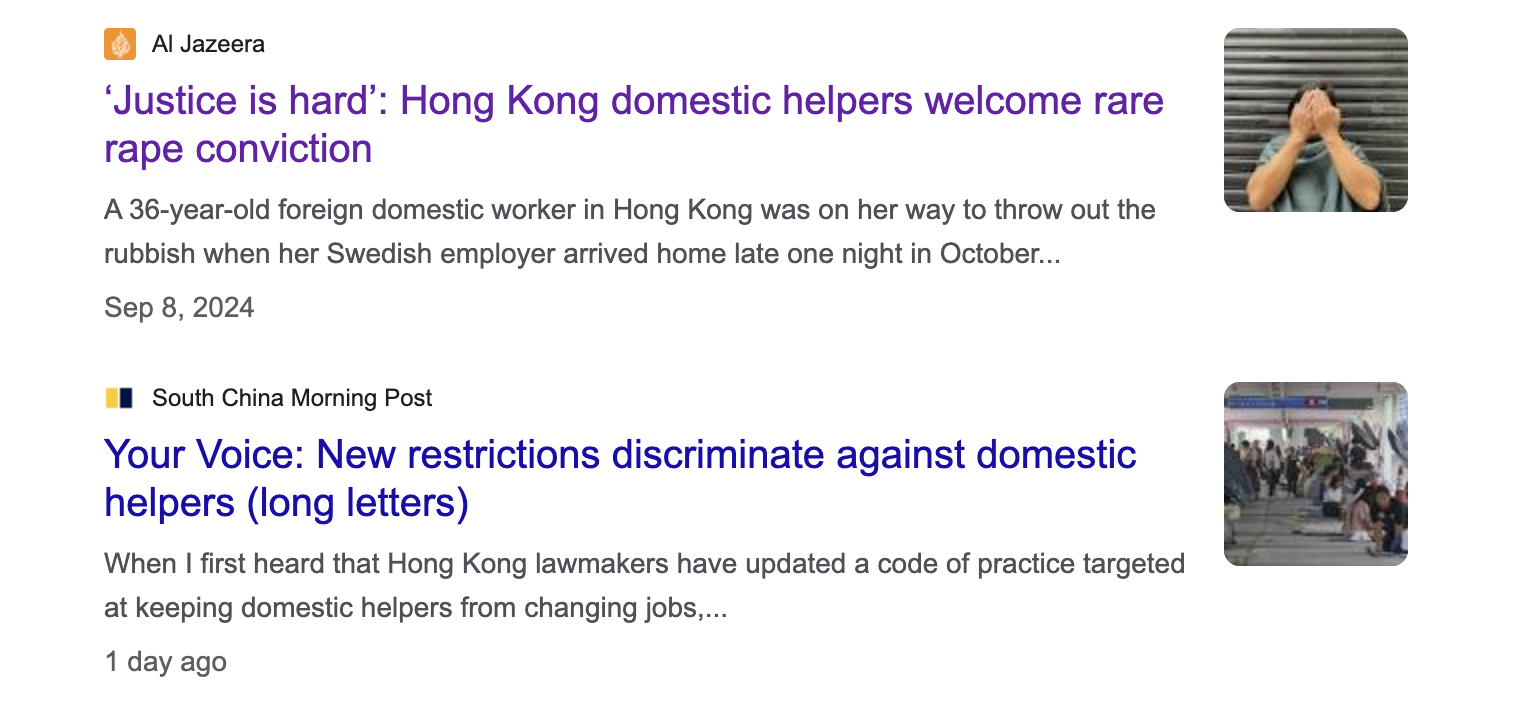

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Media spotlight on justice and discrimination: Hong Kong domestic helpers navigate systemic challenges.

Policies - The exploitation of FDWs in Hong Kong is not merely a byproduct of interpersonal abuse but a systemic issue reinforced by institutional barriers and restrictive policies. These structures, deeply embedded in legal frameworks and societal attitudes, create a culture that normalizes mistreatment while limiting avenues for reforms.

|

Policies Being Highlighted |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Live in Rule |

Mandates that FDWs reside in their employers’ homes |

|

Two Week Rule |

Requires workers to leave HK or find a new employer within two weeks of contract termination |

|

Minimum Allowable Wage (MAW) |

The current MAW for foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong is HK$4,870 per month (approximately US$623) with reductions allowed for food provisions from employers |

|

Controlled Path to Permanent Residency |

Enter under a Foreign Domestic Helper Visa which is typically valid for 2 years and tied to a specific employer - if they change employers, must apply for a new visa. FDW do not have a right to vote under any circumstance. |

Hong Kong’s legal framework imposes significant restrictions on FDWs, exacerbating their vulnerability. Key policies like the live-in rule, which mandates that FDWs reside in their employers’ homes, and the two-week rule, which requires workers to leave HK within two weeks of contract termination, place FDWs in at-risk positions. The live-in rule blurs the boundaries between professional and personal lives, often leading to overwork, inadequate living conditions, and heightened susceptibility to physical and sexual abuse. For instance, reports have highlighted cases where FDWs were forced to sleep in kitchens or bathrooms, depriving them of basic dignity and privacy. The two-week rule, meanwhile, deters FDWs from reporting abusive employers, as losing their job could mean imminent deportation. This policy effectively silences FDWs, leaving them trapped in exploitative environments out of fear of losing their livelihood. These legal provisions, coupled with the deliberate exclusion of FDWs from permanent residency eligibility, unlike other expatriates who can apply after seven years, underscore their systematic marginalization within HK society.Institutional barriers like wage suppression and exclusion from standard labor protections further entrench structural inequality. FDWs are paid a minimum allowable wage, often significantly lower than the median income in HK. Additionally, deductions for food and housing are legally permissible, reducing their take-home pay to near-subsistence levels. These economic disparities, codified in law, reflect a broader societal devaluation of domestic labor and the individuals who perform it.

The live-in rule blurs the boundaries between professional and personal lives, often leading to overwork, inadequate living conditions, and heightened susceptibility to physical and sexual abuse. Amnesty International reports instances where workers were made to sleep in kitchens or bathrooms, with no personal space or privacy. In August 2013, the Mission for Migrant Workers, a Hong Kong-based NGO, released the results of a survey conducted including 3,000 FDW. The findings revealed that 58% of the women experienced verbal abuse, 18% endured physical abuse, and 6% suffered sexual abuse. The Mission believes that many additional cases go unreported due to fear or a lack of knowledge about the complaint process. Such conditions underscore the systemic vulnerabilities created by policies that prioritize employer convenience over worker well-being. The two-week rule, meanwhile, deters FDWs from reporting abusive employers, as losing their job could mean imminent deportation. This policy, often used as a tool of manipulation by employers in the same report two thirds of FDW had been subject to physical or psychological (verbal) abuse, and/or threats such as “send them back to Indonesia”, this myopic policy effectively silences FDWs, leaving them trapped in exploitative environments due to fear of losing their livelihood and subsequently their ‘citizenship’. These legal provisions, coupled with the deliberate exclusion of FDWs from permanent residency eligibility, unlike other expatriates who can apply after seven years, underscore their systematic marginalization within HK society. Institutional barriers like wage suppression and exclusion from standard labor protections further entrench structural inequality. FDWs are paid a minimum allowable wage, often significantly lower than the median income in HK. Additionally, deductions for food and housing are legally permissible, reducing their take-home pay to near-subsistence levels. These economic disparities, codified in law, reflect a broader societal devaluation of domestic labor and the individuals who perform it. Further compounding these vulnerabilities, just over half of FDWs (51 out of 93 interviewed by Amnesty International in 2012) did not receive the statutory weekly rest day mandated by Hong Kong’s Employment Ordinance. This denial not only reflects the systemic normalization of rights violations but also isolates workers, cutting them off from opportunities to access support networks or report abuse.

Beyond wages, FDWs face restrictions on freedom of movement and association, particularly during crises. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, FDWs were subjected to discriminatory measures, such as being prohibited from leaving their employers’ homes on rest days. These restrictions were not applied uniformly across the population, reinforcing perceptions of FDWs as a subordinate class whose rights are secondary to the convenience and comfort of their employers.

Framing, Media, and Policy

The role of the media in legitimizing these structural inequities cannot be overstated. As noted in recent studies, Hong Kong’s Chinese-language media frequently engages in perpetrator exoneration and victim blaming. By framing FDWs as "lazy" or "incompetent" and highlighting employers’ stress or personal challenges, these narratives shift public empathy away from the workers and toward the employers. Such portrayals reinforce public acceptance of restrictive policies, framing them as necessary to regulate an “untrustworthy” workforce rather than as instruments of systemic control. The legal restrictions imposed on FDWs are rationalized by stereotypes perpetuated in the media, which in turn influence public opinion and policy enforcement. This cyclical dynamic ensures that systemic barriers remain firmly in place, making it exceedingly difficult for FDWs to advocate for themselves or seek meaningful reform.

Global Implications and Patterns.

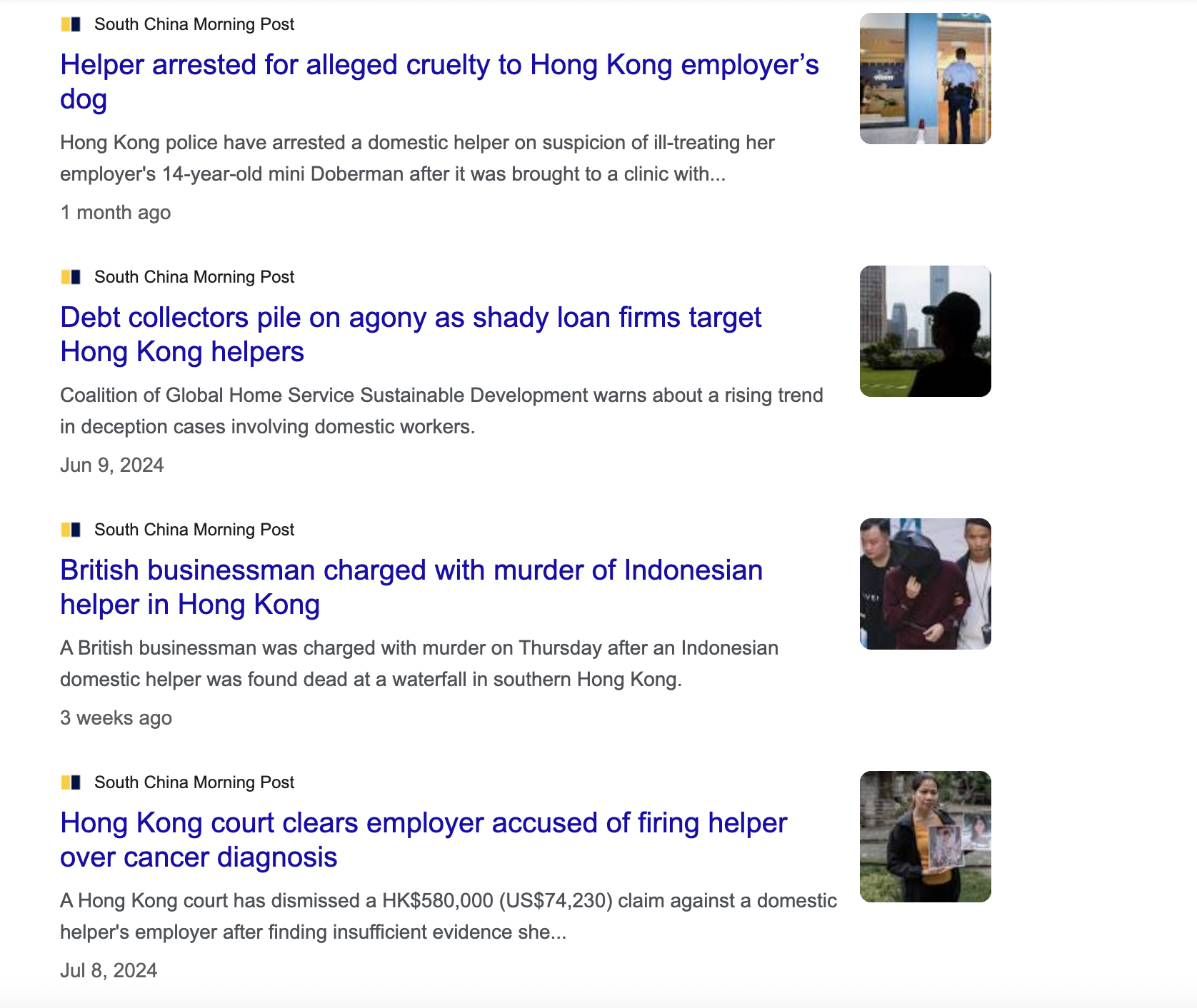

The experiences of FDW in Hong Kong reflect larger global patterns stemming from the interconnected forces of neoliberal capitalism and globalization. The movement of women from the Global South to the Global North for employment, particularly in domestic and care work, is emblematic of structural inequalities that span national borders. This migration trend is driven by systemic disparities in economic opportunities and perpetuates a cycle where women from developing nations are disproportionately relegated to undervalued and precarious labor.

These patterns are not unique to Hong Kong; they represent a global phenomenon where migrant workers often face overlapping forms of oppression—interpersonal, ideological, institutional, and internalized. Across regions, migrant women encounter exploitation tied to their positionalities, as factors such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status shape their access to resources and protections. The hardships faced by FDWs are thus part of a broader crisis, highlighting how global systems prioritize capital over the well-being of marginalized communities.

The movement of women for employment purposes in the domestic sector underscores the gendered dimensions of global labor migration. Wherein women disproportionately bear the brunt of caregiving roles while navigating societal structures that devalue their contributions. It also illustrates how neoliberal policies commodify human labor, perpetuating exploitative practices that reinforce systemic inequities. Understanding these global dynamics is crucial, as it sheds light on the broader implications of a system that normalizes the dehumanization of migrant workers, emphasizing the urgent need for global frameworks that advocate for equity, dignity, and justice..

Infographic illustrating the changing world of work and its impact on gender equality. Source: UN Women, The Changing World of Work [Interactive infographic]. Retrieved from https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/infographic/changingworldofwork/en/index.html"

Infographic illustrating the changing world of work and its impact on gender equality. Source: UN Women, The Changing World of Work [Interactive infographic]. Retrieved from https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/infographic/changingworldofwork/en/index.html"

Concluding Remarks and Suggestions

To address policy myopia, it is crucial to integrate adaptive and intersectional approaches into policy development. Adaptive policies, that emphasize flexibility and ongoing learning, can better account for the uncertainties and complexities inherent in governing diverse societies (Nair & Howlett, 2017). These adaptive policies should apply an intersectional lens that can help the public and political gatekeepers understand and address the compounded challenges faced by FDW. By doing so, policymakers can move beyond short-term fixes and create frameworks that foster equity and inclusion, ultimately challenging the structural inequalities that policy myopia often reinforces.

Addressing these institutional barriers requires a multifaceted approach. Legal reforms, such as abolishing the live-in and two-week rules, implementing fair wage structures, and extending permanent residency eligibility to FDWs, are essential first steps. Equally important is challenging the media narratives that dehumanize and marginalize this population. Journalistic accountability and public education campaigns could shift societal attitudes, fostering greater recognition of FDWs as essential contributors to Hong Kong’s economy and society. Ultimately, dismantling the pervasive culture of exploitation requires confronting the structural inequalities embedded within Hong Kong’s policies and practices. Only by addressing these foundational issues can the rights and dignity of FDWs be fully realized.

To successfully dismantle these inequalities, it is essential to engage in a comprehensive dialogue between government agencies, media outlets, civil society organizations, and affected communities. Collaboration across these sectors of cultural output can help to ensure that policies reflect the lived experiences of migrant domestic workers (FDWs) and are informed by their voices. Additionally, international frameworks, such as those put forth by the International Labour Organization (ILO), can provide critical guidance in aligning Hong Kong’s policies with global standards of human rights and labor protections.

Policy reform alone will not suffice without a fundamental cultural shift. It is necessary to foster a societal recognition of the inherent dignity and rights of all workers, regardless of nationality or immigration status. This shift involves not only legal reform but also a reevaluation of the cultural narratives that perpetuate the marginalization of FDWs. Education, advocacy, and awareness-raising efforts aimed at both the public and key decision-makers are essential to promoting a more inclusive and just society.

The path toward genuine equity for FDWs in Hong Kong requires an intersectional approach that acknowledges the complexity of their experiences and the need for systemic change. Through legal reform, media accountability, public education, and international cooperation, Hong Kong can move towards a future where migrant domestic workers are recognized, valued, and treated with the dignity they deserve. Only through such a comprehensive approach can the enduring cycle of exploitation be broken, ensuring that the rights of all workers are upheld.

Chen Z (2024) How does the media contribute to the rise of hate crimes against foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong? An unfair problem frame and agenda setting. Front. Sociol. 9:1374329.

doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2024.1374329

Chan, B.K. (2009). To what extent do the news media influence policy making? : a case study of the press and policy making in Hong Kong.

China (Hong Kong): Submission to the Legislative Council’s Panel on Manpower – “policies relating to foreign domestic helpers and regulation of employment agencies” - Amnesty International. (2021, August 10). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa17/005/2014/en/

Yuen, C. (n.d.). Almost 95% of foreign domestic workers exploited or forced into labour in Hong Kong - Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. Hongkongfp.com. https://hongkongfp.com/2016/03/15/almost-95-of-foreign-domestic-workers-exploited-or-forced-into-labour-in-hong-kong/

Ho, J., & Sewell, A. (2023). Exploring mediated representations of migrant domestic workers in the Chinese-language media in Hong Kong. Ethnicities, 23(6), 146879682311647. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968231164721

Crenshaw, K. (2013). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Feminist legal theories (pp. 23-51). Routledge.

Hutton, M. (2024, November). Migrant workers’ coalition expresses “sorrow and anger” over suspected murder of Indonesian domestic worker. Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. https://hongkongfp.com/2024/11/01/migrant-workers-coalition-expresses-sorrow-and-anger-over-suspected-murder-of-indonesian-domestic-worker/

McCafferty, G. (2013, March 25). Hong Kong’s foreign maids lose residency fight. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2013/03/25/world/asia/hong-kong-maids/index.html

Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9916.2007.00326.x