A Society in Crisis

An Analysis of the Intersection Between South Korean Society and Mental Health

Korean culture is something that has interested me for awhile. Between my friends' influence and my own discoveries, I have come to enjoy Korean food, music, and media, and I will be studying abroad in South Korea this summer. My interest in Korean culture alongside my career aspirations to work in the field of psychiatry inspired me to look into the state of mental health in South Korea, and I was met with some interesting (and ultimately concerning) results.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), South Korea has among the highest suicide rates in the world, sitting at 24.1 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2021 (OECD 2020). For comparison, the US rate for that year was 14.1 deaths. This rate reportedly increased to 27.3 as of 2023, which is the highest yearly rate since 2014 (Kang & Lee, 2024). These rates have increased for certain demographics in particular, such as those in their 20s to 30s as well as the elderly population (K-DOC 2023; Song 2023). Despite various measures being implemented in recent years to address these concerning statistics, suicide rates have not decreased yet, and have instead experienced an uptick. This shows that there are still underlying problems/factors that have yet to be addressed.

For this study, I began by summarizing the development of mental health institutions in South Korea and explaining the progression of the mental health crisis that is being experienced. I then examined three particular factors within Korean society to see how they have contributed to worsening mental health. These three factors were South Korea’s rapid modernization, the influence of Confucian ideals, and the intense academic culture. Factors were selected in an attempt to cover a wide range of societal considerations, although there are points of overlap between the three selected. While each of the factors I selected were relatively broad and have had certain positive impacts on those living in South Korea, for this project I focused specifically on the detrimental impacts they have made on mental health. The factor analysis was followed by examination of hwabyung, a Korean cultural syndrome characterized by feelings of pent-up anger, bitterness, and resentment. Cultural syndromes are a strong way to learn more about the intersection of society and mental health because they are conditions expressly caused by unique factors of a given culture. Lastly, I summarized and critiqued the most recent mental health policies that have been proposed.

Mental health can be a tricky field to work within because there are such a wide range of contributing factors to consider for each case, and every person has their own unique personality and mindset which makes it difficult to find universal solutions for any given issue. Despite this, when mental health problems are highly prevalent within a specific group of people, examining the society that they exist within can help analyze specific contributing factors and point towards more productive avenues of treatment and more effective policies. Through a close examination of a selection of aspects of Korean society, the aim of this project is to identify some of the stronger factors contributing to the present mental health crisis, and provide a critique of current plans/solutions being proposed.

This brings us to the central research question:

In what ways do rapid modernization, Confucianism, and academic culture within South Korean society contribute to worsening mental health for Koreans?

Furthermore, how do these factors implicate current mental health treatments and policies? How do current methods fail to account for the unique aspects of South Korean society?

Development of Mental Health Institutions & Policies

Korean shamans performing Hwanja-gut (환자굿), a healing ritual ([Hwanja-gut], 1903).

Korean shamans performing Hwanja-gut (환자굿), a healing ritual ([Hwanja-gut], 1903).

.

.\\\\\\\

.

.

.

"The 2018-closed Cheongnyangni Mental Hospital, once known as the Seoul City Mental Hospital, was originally founded in 1945 and rebuilt in 1966" (Greenberg 2022).

"The 2018-closed Cheongnyangni Mental Hospital, once known as the Seoul City Mental Hospital, was originally founded in 1945 and rebuilt in 1966" (Greenberg 2022).

.

.

.

.

.

A hallway within the Korea Suicide Prevention Center (Wonju, 2021).

A hallway within the Korea Suicide Prevention Center (Wonju, 2021).

To understand Korean mental health in the modern day, it is helpful to review the nation’s history regarding the perception of mental health, as well as its treatment and related policies. Prior to Western psychiatry, Asian traditional medicine and shamanism were the primary modes of treatment (Sung & Yeo, 2017). The Western conception of psychiatry (primarily following a biomedical outlook on mental health treatment) cemented itself during the Korean War era of the early 1950s (Shin & Yim, 2023). Unlike many other countries, in South Korea military psychiatry developed prior to civilian psychiatry, with the former having a strong influence on the latter. Korean military psychiatrists adopted many techniques from US military psychiatrists, and this knowledge was then carried back to civilian institutions, which experienced an increase in development during this time.

In the mid-1980s there was an increase in attention towards mental health (Kahng and Kim, 2010). The Mental Health Act in 1995 (which was officially in effect since 1997) set the goal of shifting policies away from long-term hospitalization and towards community mental health services. Examples of these services include social rehab centers, alcohol rehab centers, outpatient clinics, and long-term care centers. For comparison, the transition to community mental health services in developed countries started around 30 years prior to this. This initial shift, despite coming later than some countries, was promising in that the government helped support these programs and provided various services for free, increasing registration rates despite the stigma that still existed. However, despite the start of this transition, South Korea remained heavily reliant on medical and inpatient services, shown through statistics such as the increase in the number of psychiatric beds per 1,000 people from 0.25 to 1.51 from 1980 to 2005. This continued reliance on medical/inpatient services can be seen today as well, with acts that call for even more psychiatric beds to be made available (Cheon 2023). The failure to fully transition to a community-based model can be at least partially attributed to a lack of continued financial support from the government (Sung & Yeo, 2017).

The National Suicide Prevention Policy was put into place in 2004, setting various goals of reducing suicide rates (Song, 2023). These goals are yet to have been achieved. As of 2023, four such plans were passed, each with their own goals for a decrease in suicide rates. The first plan was in effect from 2004-2008, aiming to lower suicide rates to 18.2 suicides per 100,000 people - the actual rates were 31.2 per 100,000. The second plan from 2009-2013 aimed for 20, but in reality was 28.5. The third (2016-2020) had the same goal yet only decreased to 25.7, and the most recent plan (2018-2022) set a goal of 17 but seems to only have decreased to 24.4. The fifth plan came out in 2023, and has set a goal of a 30 percent reduction to 18.2 by 2027.

The Act for the Prevention of Suicide and the Creation of Culture of Respect for Life was passed in 2011, commonly referred to as the Suicide Prevention Act (Umeda 2016). Following this, the Korea Center for Suicide Prevention and the Korea Center for Psychological Autopsy were created in 2012 and 2015 respectively, later merging to become the Korea Foundation for Suicide Prevention. By 2018 suicide prevention was made into a government department for the first time, with the Department of Suicide Prevention Policy being established in the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MHW) (Song, 2023). Overall there have been various 5 year plans instituted throughout the years in relation to mental health goals, with one of the most recent ones being from 2016-2021 (Umeda 2016).

Although more mental health institutions and policies have developed throughout the years, mental health problems are still highly relevant in Korea.

The Current Problem

Korea is experiencing a mental health crisis

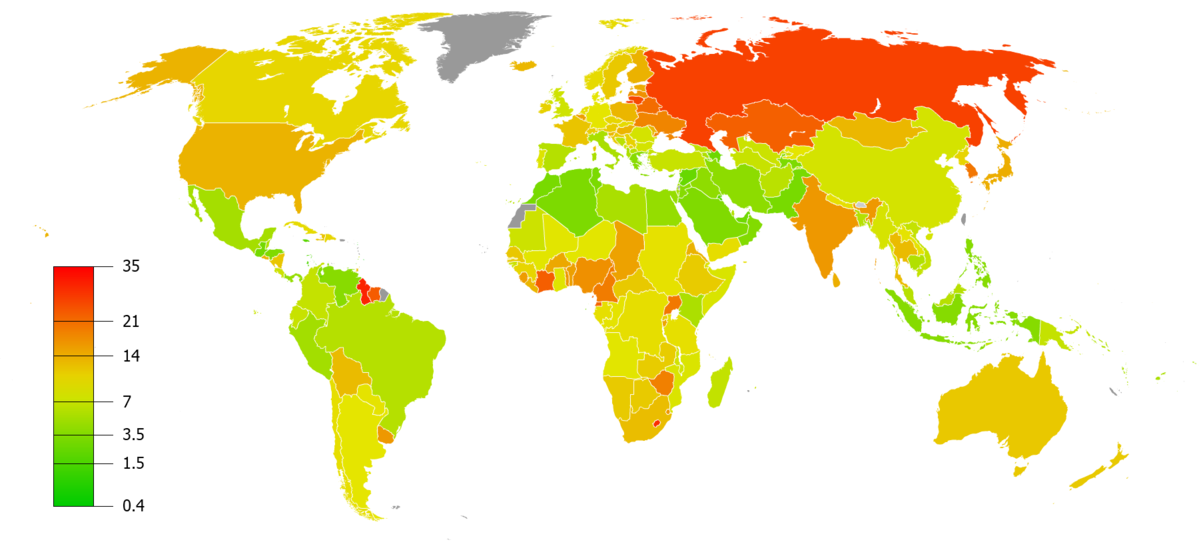

In the modern day, Korean society experiences many mental health challenges. As mentioned previously, Korea has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. The nation continues to rank first in the OECD for highest suicide rates (OECD 2020). The rate was highest in 2011 (at 31.7 deaths per 100,000 people), but has not decreased at the same rate as the global trend of decrease (Song 2023). As of 2019, South Korea had the 4th highest suicide mortality rate in the world (WHO 2022). In 2023, there was an uptick and suicide rates were at their highest since 2014 (Kang & Lee, 2024).

COVID-19 is another contributor to the current mental health crisis, as one might expect. The pandemic increased the number of families experiencing economic troubles and social isolation, which the MHW identified as contributing to increased rates of depression and anxiety disorders (Cheon 2023). The pandemic has also specifically impacted South Korean suicide rates, with one study showing an abrupt decline in youth suicide attempts, but an increase in attempt rates for older males (Kim et al., 2024).

One concerning trend has been the increase in “lonely deaths” over the past few years, a phenomenon studied in depth in a Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) documentary (K-DOC 2023). Lonely deaths are defined as people who are found a certain period of time (not specified in the documentary) after dying alone. Not all lonely deaths are suicides, but many of them are. In 2020, there were estimated to be approximately 4,200 deaths in this manner. The rate has increased especially for people in their 20s-30s. The death rate for this age group corresponds with an increase of those reporting mental health issues. For instance, from 2018-2022 the number of people in their 20s receiving treatment for depression nearly doubled (Cheon 2023). The unique struggles for this demographic might be explained by the lack of resources currently offered to that age bracket – according to a lawmaker that was interviewed, current Korean welfare is primarily for older and/or disabled people, so people in their early-mid adult years don’t always receive the help they require (K-DOC 2023). Additionally, many prominent mental health disorders have ages of onset around this age range.

Youth and elderly demographics have also been experiencing distinct mental health problems. For Korean children and teenagers, one of the leading causes of stress (and in extreme cases, suicide) is academic pressure, which will be explained in depth later in this project. As of 2017, there was a 23.02% youth prevalence for anxiety disorder, which is nearly a quarter of the youth population (Sung & Yeo, 2017). In regards to the elderly population (defined as people over 65 years old), the same study reported a 10.1% prevalence for depression, and a high prevalence of dementia (8.1%). The suicide rates for the elderly are also extremely elevated, with about 34 deaths per 100,000 people in their 60s, 46 for those in their 70s, and 67 for those over 80 (Song 2023). These rates are often attributed to high rates of elderly poverty in the nation, due to a lack of public welfare system and a collapse of the private system.

To fully understand these concerning statistics and what caused this mental health crisis for Koreans, one must examine various unique aspects of Korean society.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

A map of suicide rates globally, according to the WHO as of 2016 ([Suicide rates map], 2019).

Theoretical Framework

How can we approach analysis of the problem?

Within this project, a broad framing technique I utilized was a focus on biological anthropology, rather than the traditional biomedical model that is often used to discuss health issues. To do so, I relied on analysis made by Syme and Hagen regarding why mental health is better suited to the field of biological anthropology (Syme & Hagen, 2019). They point to how the current prioritization of psychopharmacological treatments for mental health disorders often have weak efficacy in fully treating symptoms, and don’t address the root cause of problems – this is why there has been increases in treatment rates for certain disorders, yet no major decrease in overall prevalence rates. The researchers reference Arthur Kleinman, notable for his work on analyzing the way culture shapes experience of illness. As of now only a small portion of biological anthropological studies have focused on mental health, leaving it as an untapped avenue. While Syme & Hagen make it clear that a fully coherent theoretical framework for studying mental health under biological anthropology does not yet exist, the generalized critique they set forth regarding the ways biological psychiatry can fail was used in this project as an overarching framing issue. I chose this as a relevant framing because many of the recent/current advancements in mental health for South Korea seemed to fall under biological psychiatry, and they were failing to create meaningful change. Therefore, it stands to reason that there is some sort of weakness with the current approach, requiring a different theoretical framing for analysis – one that looks at mental health in a new way, incorporating the anthropological aspects of studying factors across cultures and incorporating the subsequent results into any suggestions for future policies.

Analyzing the Factors

Examining the negative impact of selected Korean societal dynamics and culture on mental health

Rapid modernization, Confucianism, and an intense academic culture each impact the lives of Koreans, producing negative mental health outcomes.

Rapid Modernization

.

.

A photo of Seoul, the capital of South Korea (Jung-Kim, 2024).

A photo of Seoul, the capital of South Korea (Jung-Kim, 2024).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

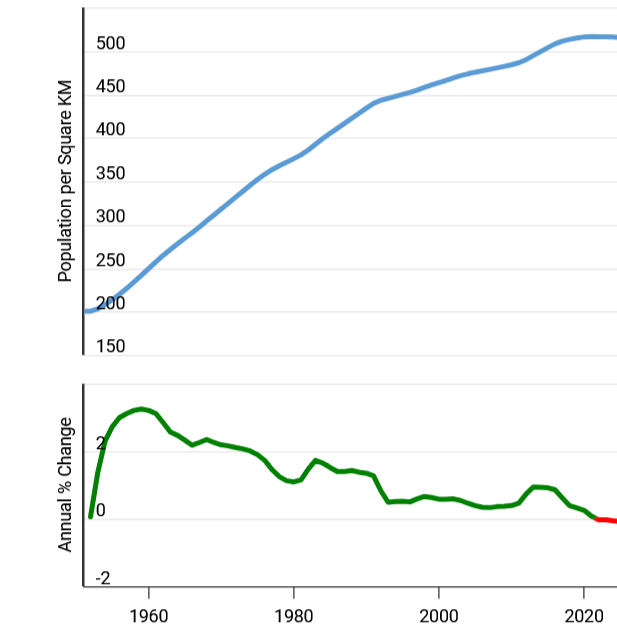

Graph of South Korea population density from 1950-2024, including the average percent change each year (SK Population Density, 2024).

Graph of South Korea population density from 1950-2024, including the average percent change each year (SK Population Density, 2024).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Yeoyu is a term meaning space, that can apply in both the literal and figurative sense. The lack of physical space in Korea due to population density might impact the mental state of Koreans (Rose 2023). The rapid modernization of South Korea likely contributed to the higher population density, especially in major cities, and the resulting lack of space.

Over the past decades, South Korea has undergone a series of rapid socioeconomic changes. This has resulted in a quick push towards industrialization and urbanization, alongside a shift from the extended family unit towards more of a nuclear family system. These factors combined have resulted in negative mental health outcomes. The rapid changes induced high levels of stress, and the collapse of traditional family care methods meant greater visibility for those who were suffering. This has resulted in a statistical increase for various mental health issues (Kahng & Kim, 2010).

South Korea is not the only nation to experience rapid modernization in this manner – China, Taiwan, and Japan all went through a similar transition. What’s interesting to note is that all of these countries have a shared emphasis on Confucian values, which can often run contradictory to the ideals of modernization and industrialization. South Korea went through a period of devastation by war, suffering greatly from World War II and then in their civil war from 1950-53. The country was becoming densely populated, yet remained relatively resource poor, similarly to the other aforementioned countries. Despite these challenges, the nation was still able to undergo rapid modernization and industrialization, and even managed to do so at a relatively low level of income inequality.

Unfortunately, the current modernized and urbanized state of the nation has had some negative ramifications on mental health. The unemployment rate reached three times the national average (prior to the pandemic), and urban centers such as Seoul (the nation’s capital) have major housing problems. The housing crisis caused approximately 40% of young people to stop seeking work, contributing to a generalized feeling of hopelessness and financial distress (Nagar 2022). Many cases of lonely deaths occur in major city centers, where people live alone in small apartments, getting by day-to-day working stressful jobs that are often focused on manual labor which can lead to various injuries and complications (K-DOC 2023). Additionally, urban life often pushes people into a more individualized mindset, and this isolation can cause psychological distress.

With modernization, population density often increases as more people move into cities, creating densely populated spaces. While South Korea’s population density experienced a slight decrease in the past couple of years, this was only after a nearly 75 year trend of population density increase. In 1950, the nation’s population density was 200.32 people per square kilometer, which consistently increased for 70 years, reaching 516.59 people per square kilometer in 2020. 2021 was the first year this statistic experienced a slight decrease, and as of 2024 the number is at 515.56 (SK population density, 2024). There is a Korean term that could be useful in understanding how this might impact mental health. The term is “yeoyu”, which is defined by the Korean dictionary in two ways: “1) a state of material, temporal or spatial sufficiency; or 2) a state of being in which one is able to think or act leisurely/calmly” (Tizzard 2023). When translating this term into English, it is often likened to the word “space”, both in the physical and the mental sense. In a video by Rebecca Rose of the Halfie Project, she explains the term in more depth and posits how having a lack of physical space can affect one’s mental “space” – with a lack of mental space, there can be a negative impact on overall mental health. The video linked on this page goes a bit more in depth regarding the concept and its applications. The high population density in South Korea – especially in the major cities – would mean that residents of those areas would experience a lack of physical yeoyu, which could then hurt their mental state. Abundance and yeoyu exist essentially in opposition – having many material possessions can give you an abundance of things, but a lack of yeoyu. Major city centers have an abundance of things (buildings, people, events, etc), but that directly limits yeoyu. While understandings of yeoyu are good for explaining effects that urban centers can have on mental health, this analysis wouldn’t apply to those living in rural areas of South Korea. Additionally, there is a lack of scientific studies on this phenomenon, at least in the Korean context, so it warrants further research. However, yeoyu can be applied globally because despite existing as a Korean term, the meaning of it is not exclusive to Korean society. This means it can be extrapolated to other countries/regions with high population densities such as Monaco, Singapore, Hong Kong, etc. This concept would also be applicable for anyone living in specific cities that are densely populated.

It is impossible to entirely erase the psychological stress that urbanization and modernization can cause for people, especially those living in major metropolitan areas. This makes it imperative to take specific communities into consideration when creating mental health policies. People living in the middle of Seoul would benefit from policies that account for the stress caused by living in a densely populated, more modernized area, whereas people living in rural South Korea would not need those same measures.

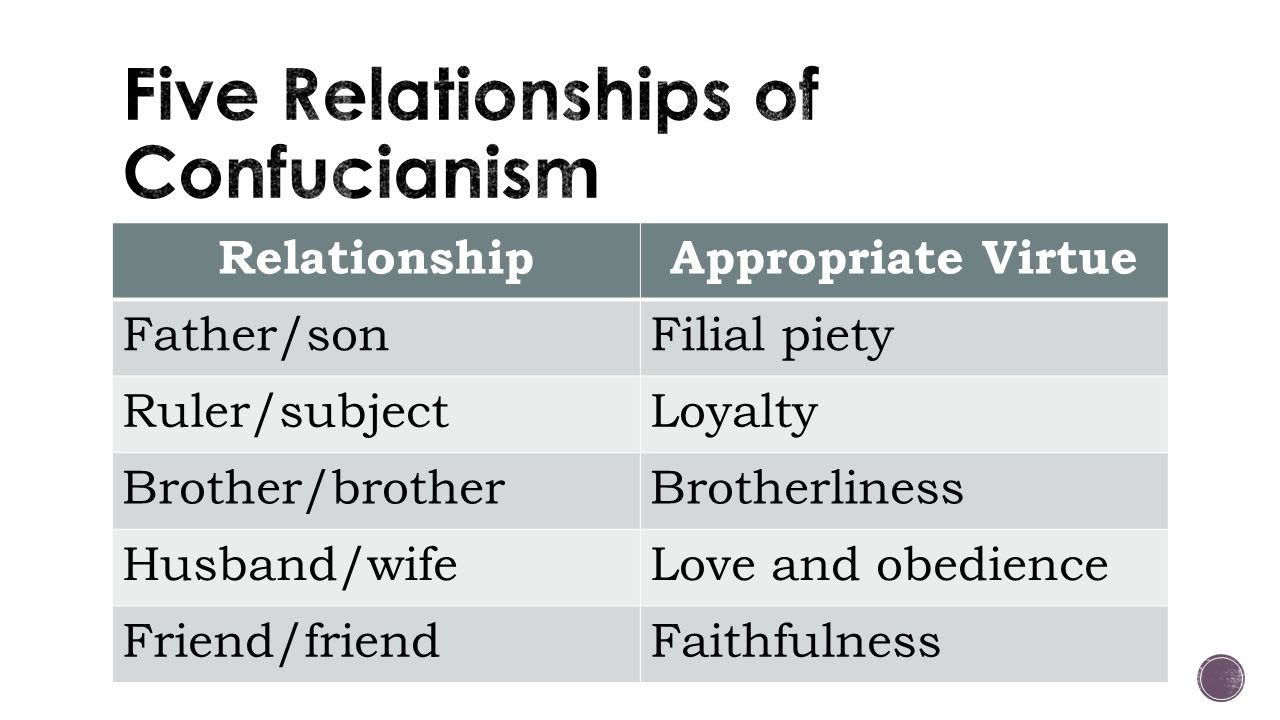

Confucianism

Korean culture and society is greatly impacted by the tenets of Confucianism. Confucianism is a belief system that began in China, later spreading to other Asian countries/regions such as Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Vietnam. Confucianism in Korea can be traced back to the late 14th century in the Yi dynasty, which ended in 1910 with Japan's annexation of Korea (Hyun 1995). The eight cardinal virtues of Confucianism are loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, affection, trustworthiness, righteousness, harmony, and peace (Badanta et al., 2022). Confucianism is characterized by strict social hierarchies and a strong sense of duty/responsibility towards others, especially those older than you. Even for Koreans today who don't actively practice Confucianism, the belief system has existed in Korea for so long that many of its ideals are deeply intertwined with Korean culture, contributing to the collectivist nature of Korean society.

The practice of filial piety is one specific aspect of Confucian beliefs that can have a direct negative impact on one’s mental health. Filial piety can be defined as the respect and deference that is paid to one’s parents, putting their interests above your own. This can lead to neglect of personal mental health conditions – because filial piety (and Confucianism in general) dictate that certain duties and obligations must be performed for parents and other older relatives, people might feel shame and guilt for focusing on themselves instead. This can lead those people to refrain from seeking help for themselves, deeming it a selfish course of action (Badanta et al., 2022). A past study supported this logic, showing that women with depression who obeyed filial piety had increased suicide cases (Jia & Zhang, 2017).

Other psychological studies also support how Confucian beliefs can play a role in an individual’s mental health. In a study conducted by Oh et al., it was found that for Korean-American students, family obligation values (FOV) were associated with motivation, self-esteem, and depression, more so than for European American students (Oh et al., 2020). This study was conducted under the framing of Self-Determination Theory, depicting self-determination (the capability to be independent and shape one’s own life) as an ideal of human development. FOV are an aspect of collectivist cultures (such as Confucian Korea) that consists of prioritizing family obligations over personal ones. For the purposes of the present study, FOV can be deemed synonymous with filial piety. As part of Oh et al.’s results, there was a stronger association between FOV and depression for Koreans than European Americans. Students who considered their parents supportive of their self-determination reported lower depression rates, and since this association was stronger for Korean Americans, it supports the conclusion that FOV have a greater impact on those who are part of collectivist cultures. While this is framed as beneficial within Oh et al.’s study, it also implies that for students who DON’T have a supportive family, they will be more negatively affected than those who aren’t from collectivist cultures. This general conclusion is also supported in a study by Kwon and Kim, who examined the ways that a country’s level of collectivism vs individualism can impact the mental state of those who live there (Kwon & Kim, 2024). They surveyed students from different countries regarding their satisfaction with life and their level of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy was defined as one’s belief in their ability to take action to achieve their goals despite setbacks they face. The results of the study supported the researchers’ hypothesis that cultures with a greater emphasis on collectivism would be less impacted by self-efficacy, an individualistic value. These two sample studies both support how people in collectivist cultures have different values, therefore will be motivated by different factors.

Additionally, Confucianism can shape how Koreans ground their self-conception; as opposed to Western cultures, Korean self-conception has a deeper connection to interpersonal relationships, especially that between family members. Overall this results in a “we consciousness” that is even apparent in the Korean language itself (Hyun 1995). This other-focused self-conception can be helpful by prioritizing emotions like sympathy and interpersonal communion, but it can also cause shame for people experiencing individual emotions that might be deemed as selfish. For instance, someone who is stuck in bed all day dealing with a depressive episode might be seen as neglecting their duties to go to school/work, help their family, etc.

Due to how deeply Korean culture is rooted in Confucian ideals, mental health policies that don’t take this into account are bound to be negatively implicated. Even if the policy being proposed in and of itself is a good idea, it might need to be altered in its presentation to be effective for those with Confucian ideals. For instance, in the US there has been a recent emphasis on taking self-care days and prioritizing one’s own time and needs. A movement centered around this ideal would likely have more difficulty gaining traction in South Korea, because on face value it would be seen as contradictory to the underlying Confucian beliefs many Koreans hold. Another easy to understand example would be suicide prevention education. In the United States, movements that educate on suicide prevention usually further the notion that it is okay to ask for help and to advocate for yourself. This can also be seen in more generalized mental health movements that advise people to take mental health breaks, set healthy boundaries, and prioritize self-care. While these practices might be beneficial for Koreans too, they would have to be presented in a manner that accounts for the slight contradictions between those personal practices and the duties/obligations present in collectivist societies. In more extreme examples, mental health measures that are successful in individualistic countries might just fail entirely in collectivist societies that choose to reject them for their contradictions with concepts like filial piety.

As a related factor, Korean attitudes towards work ethic and academics are different from the US and have an impact on mental health.

This table shows the five core relationships defined under Confucianism, as well as the virtue that is connected with it ([Five relationships], 2020). With each of these relationships, there are certain duties/obligations that one side is believed to owe the other.

This table shows the five core relationships defined under Confucianism, as well as the virtue that is connected with it ([Five relationships], 2020). With each of these relationships, there are certain duties/obligations that one side is believed to owe the other.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Brief summary of Confucianism in Korea (The Korea Foundation, 2013).

Academic Culture & Work Ethic

A typical Korean classroom (Shin, 2021).

A typical Korean classroom (Shin, 2021).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

All Korean high school students take the suneung, the college entrance exam. It is an 8 hour exam that determines the academic future for each student, and what college they will be able to get into (The Korea Times, 2019).

Korean culture emphasizes work ethic and academic success, which can play a role in mental health (Hyojin 2023). Koreans take education very seriously, with children as young as 5 years old already being pushed to become competitive students in order to make it into the best universities (Manson 2024). Cram schools are also prevalent, with older students attending their regular classes in the morning and afternoon and then going back for more studying in the evening. Some of Korea’s intensity towards education can be connected to aforementioned Confucian values, specifically hakbeol, which can be defined as a status “based on the belief that socially desirable values (e.g., higher social status, wealth, power) are based on one’s educational achievements” (Badanta et al., 2022). Hakbeol essentially creates a hierarchy of Korean universities based on their reputation, and based on what university one attends, it is seen to reflect on their personal merits (Garrison et al., 2018). This can be likened to the way some people in the US hold Ivy League schools in high regard, believing that a student from a school like Harvard is inherently more worthy and successful than someone who attended a public university or community college. A study by Garrison et al. connected lower hakbeol to feelings of failing to fulfill filial piety. This shows how the intense academic culture of South Korea is deeply rooted in collectivism and Korean societal values, so it isn’t likely to change anytime soon. The pressure to make it into a prestigious college is exemplified by South Korea’s college admission test, the suneung. This is South Korea’s equivalent to the SAT exam, except it takes 8 hours, and has a greater impact on what universities students are able to get into. The video linked on this page gives some more information on the suneung. Overall, it’s clear to see that the academic environment in South Korea puts a lot of pressure on students.

Aside from generalized academic stress, there is also a significant economic effect experienced due to South Korean academic culture. The pressure for academic success leads many parents to enroll their children in cram schools and other forms of private education. Spending for private education reached almost $20 billion in 2022 (Hyojin 2023). Parents reportedly spend anywhere between 15 to 30 percent of their budget on private education (Jarvis et al., 2020). This cost is not limited to explicit program fees – there are also various “hidden costs” that are not always initially considered. This includes the price of tutoring, supplemental texts, etc.

Academic stress is cited as the most common reason for life dissatisfaction by South Korean youth (Jarvis et al., 2020). According to a 2022 survey by World Without Worry About Shadow Education, 1 in 4 South Korean teenagers have considered suicide due to academic stress. The rates of attempted suicides have increased, and it reached the point that city officials in Sejong mandated the locking of rooftop doors on buildings heavily populated by students as a preventive measure. These problems are exacerbated by legal issues that make it difficult for children to pursue psychiatric help without explicit parental permission (Hyojin 2023). The severity of this issue is further exemplified in one post-COVID study which found that there was an abrupt decline in youth suicide rates following the pandemic (Kim et al., 2024). This shift is theorized to be due to the sudden removal of the intense academic environment – at least for a short period of time, schools weren’t able to fully operate, so some of the intense burden of academic success was lifted from school-aged children. If this is true, and children felt happier and less stressed at the start of a global pandemic as compared to during their normal lives at school, this suggests that academic stress is a strong negative factor for youth mental health in South Korea.

Since 2007, suicide has been the leading cause of death for Korean youth, with academic stress being the most common reason (Jarvis et al., 2024). This implicates how effective certain measures to address mental health can be. If it’s true that academic stress is the leading cause for suicide among Korean youth, then it stands to reason that the intense academic culture must be accounted for in any preventative policies. Otherwise, future mental health movements will only be treating the symptoms rather than the underlying problem. This examination of Korean academic culture and its connection to negative mental health outcomes also suggests that different age demographics might require different approaches in terms of mental health programs. While improving youth mental health would require grappling with academic stress, the same isn’t true for older demographics that have already completed their schooling.

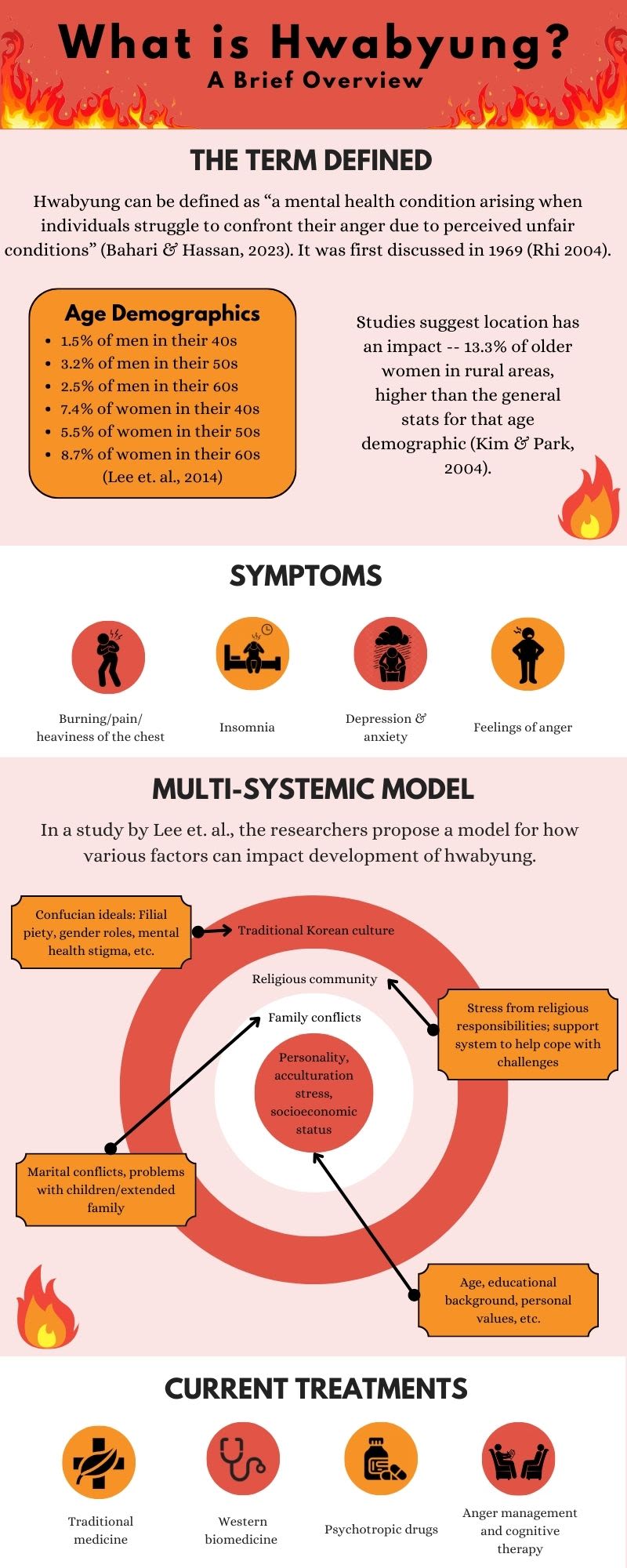

Hwabyung

A Korean cultural syndrome

Hwabyung is a cultural syndrome experienced by various Koreans, both those living in South Korea and those who immigrated to other nations. The term cultural syndrome can be defined as “a pattern of mental illness, distress, and/or symptoms that is unique to a specific ethnic or cultural population and does not conform to standard classifications of psychiatric disorders” (APA 2023). These conditions can only be fully understood within their cultural context, thus providing a clear snapshot into the intersection between culture and health (Bahari and Hassan, 2023). Previously known as cultural bound syndromes, there has been a shift away from that phrasing to reflect the fluid-like nature of these conditions. Due to cultural exchanges and pre-existing similarities, it can be difficult to claim with 100% certainty that a condition is unique to a specific culture. However, despite the flexible nature of cultural syndromes, they can be helpful in illuminating aspects of a given society's culture and how it impacts health outcomes.

Hwabyung is a Korean cultural syndrome where people struggle to confront feelings of anger and resentment, typically towards a perceived injustice. 4.95% of middle-aged women have hwabyung, and this rate is even higher at 13.3% for older women in rural areas (Bahari & Hassan, 2023). The infographic to the right further explains the condition and lists some common symptoms. In previous studies, various factors have been identified as contributing to the transmission of hwabyung. In terms of societal factors, connections have been drawn to massive riots and political upheaval in Korean history, and feelings of injustice resulting from Korean occupation and past wars. Some more personal risk factors include things like marital problems, socioeconomic status, and even one's personality.

One interesting factor that is unique to Korean culture is the experience of han (sometimes romanized as haan). Han relates to feelings of bitterness and repressed anger in response to perceived injustices (Min 2009). It lacks a direct English translation, but can be roughly translated to emotions such as grudge, spite, regret, and lamentation. Han stems from Korea's tragic national history, with examples including the loss of old kingdoms in Manchuria and Koguryo, Japanese colonization, and the Korean War. This emotion can also arise from a traumatic personal life (Min 2009).

The Multi-Systemic, ecological model of hwabyung can be useful in understanding what factors contribute to hwabyung (Lee et al., 2014). Unlike previous models that focused on individual factors, the ecological model incorporates many different factors, both those from the previous models and aspects that were traditionally neglected in research. While this model runs the risk of being too general, and does not establish a threshold of what the necessary vs sufficient factors for developing hwabyung are, it provides the most holistic model for analyzing the condition. It strongly corresponds to the biological anthropological view of mental health, not limiting the causes of psychological conditions to purely biomedical reasonings.

Hwabyung deserves more attention and research, due to its likely connection to suicide rates and the overall mental health crisis in Korea. Because the elderly suicide rate is exceptionally high, it’s important to look into conditions that disproportionately impact older Koreans, which is true for hwabyung. Utilizing the ecological model of hwabyung can also serve as a potential explanation behind generalized mental health problems experienced by the elderly demographic. Since the model is so broad, even if a given individual is not diagnosed with hwabyung, identifying what risk factors they have could still give insight into mental health measures that would be helpful if implemented.

.

.

.

.

Artistic representation of han, a Korean-specific emotion that relates to feelings of bitterness and repressed anger (Elizalde, 2018).

Current Policies

"Minister of Health and Welfare Cho Kyoo-hong announces an overhaul of the country’s mental health policy at the government complex in Seoul on Dec. 5. (courtesy of the Ministry of Health and Welfare)" (Cheon 2023).

"Minister of Health and Welfare Cho Kyoo-hong announces an overhaul of the country’s mental health policy at the government complex in Seoul on Dec. 5. (courtesy of the Ministry of Health and Welfare)" (Cheon 2023).

The wide array of mental health problems in Korea have inspired some recent action by government officials. In December 2023, a new mental health plan was announced that offers mental health checkups every 2 years to people 20-34 years old, as opposed to the previous policy of providing checkups every ten years for those between the ages of 20 and 70 (Park 2023). The MHW’s mental health policy coordinator, Lee Hyeong-hoon, explained that the preventative measures focused on that specific age group because it is the time where various severe mental health disorders like schizophrenia and depression tend to onset (Cheon 2023). In the future there are plans to expand to all age groups (Park 2023). The plan also includes creating a new mental health hotline, online text therapy, the establishment of a joint emergency response center, and increased suicide prevention education. These initiatives are all part of a new 5 year plan that invests 780 billion won into mental health services (Cheon 2023). In public discussions, President Yoon emphasized how improving mental health is important for South Korea to grow as a nation, referencing the current low birth rates as a motivating factor.

While an increased focus on mental health improvement can generally always be seen as something beneficial, it is interesting to note how much of the proposed improvements and policy changes revolve heavily around the purely biological model of psychiatry, contradicting some of the ideals set forward thirty years ago in the Mental Health Act of 1995. Efforts to increase the number of psychiatric beds as well as personnel working in inpatient centers aren’t necessarily a BAD thing, but they don’t fall in line with the transition away from long-term hospitalization and towards community mental health services. This is especially the case in regards to the MHW’s plan to review the merits of introducing a “judicial hospitalization system”, where courts could order those with a mental illness to be hospitalized. This seems to directly contradict a movement away from long-term hospitalization.

When considering the biomedical approaches being implemented within recent policies, especially the push for more psychiatric beds, one must take into account that South Korea is currently experiencing a widespread junior doctor strike. The strike began on February 20th, 2024 in response to the Korean government's push to recruit more medical students (Kim & Song, 2024). Major complaints included how schools aren’t equipped to handle the increased student quotas, and the extra recruits would likely go to the higher-paying professions, leaving shortages in key areas of medicine like pediatrics and emergency departments. Even a week after the strike began, it had already resulted in many canceled medical treatments. The Korea Medical Association has expressed public support of this strike, which is still ongoing. The strike has had ongoing tangible effects on the healthcare system, reaching the point where a two week special emergency medical response period was called for by the government, and military doctors were getting sent to work at some hospitals to make up for those on strike (Lee 2024). Seeing as this strike is ongoing, this implicates the ability for certain biomedical policy approaches towards mental health to have an effect. For instance, it won’t matter if there is an increase in the number of beds for psychiatric patients if there are no doctors available to treat the patients.

Overall, the current mental health interventions being forwarded by the South Korean government seem to miss the mark in various capacities, lacking the nuance to help a varied population and relying too heavily on biomedical approaches as opposed to community-based options.

Takeaways

It is clear that Korean mental health is shaped by a variety of societal factors. This project considered a small selection in depth, focusing on the nation's rapid modernization, Confucian background, and strong work culture. Problematizing unique aspects of Korean society can aid in drawing connections between various factors that impact mental health, helping us determine which ones play what role in the ongoing mental health crisis. Examining causal relations can serve as a helpful precursor to creating effective solutions. The research compiled in this project can lead us to a few conclusions.

Despite the push starting in 1995 to focus on more community-focused interventions for mental health, the most recent policies that have passed focused primarily on biomedical approaches, such as a push to increase the number of beds in hospitals devoted to mental health treatment (Cheon 2023). This biomedical approach can also be seen through President Yoon's decision to increase medical schools' quotas for students (which has been met with major backlash from junior doctors and various members of the medical community) (Kim & Song, 2024; Lee 2024). The problem with biomedical approaches is they often don’t consider cultural contributors to mental health conditions. Seeing as this project has already established clear connections between cultural aspects of Korean society and how they produce negative mental health outcomes, it stands to reason that mental health policies that don’t account for culture and Korean society are doomed to fail to address the root cause of any problems. While it can be good to treat symptoms of a problem, it is hard to attain true prevention under that model.

Additionally, the analysis of factors seemed to suggest distinctly different motivators behind suicide rates and generalized poor mental health outcomes among different age demographics. To address suicide among youth, policies and interventions around academic stress would be the best way to proceed. For the elderly, conditions like hwabyung as well as deep-rooted Confucian beliefs are more likely to be the cause behind psychological distress. For individuals in their 20s to 30s, measures that address the lonely death phenomenon and deal with common psychological disorders would likely help, along with a focus on stress caused by living in modernized urban areas. While proposing specific plans and policy actions is beyond the scope of this project, this does serve to further the critique of current policies that exist in South Korea. They tend to remain broad, don’t vary among demographics, and sometimes only address one specific group (for example, increasing mental health check-ups specifically for those in their 20s-30s). Creating a wider range of more nuanced policies would likely be met with more positive results than current methods.

When moving forward with future research, it is crucial to approach studies such as this one from an objective position, placing oneself in the societal position of the demographic being studied. Otherwise researchers run the risk of letting preconceived beliefs and ideals shape their conclusions, decreasing the chances of creating effective and culturally aware solutions to identified problems. This is especially important for the field of mental health, which can have a very personal impact on individuals and is practiced differently among varying populations.

Recommendations for Future Work

There are various avenues to continue the research that was begun in this project. While I focused on three specific cultural factors to prove the general claim that Korean culture can negatively implicate mental health outcomes, there are a wide range of factors I did not analyze. These include aspects such as alcoholism in Korea, the ramifications of mandatory military service, and sexism in the nation. Researching other factors could lead to more detailed and nuanced critiques of current mental health policies, and allow for suggestions of more effective interventions.

References

Works Cited

APA. (2023, November 15) Culture-bound syndrome. https://dictionary.apa.org/culture-bound-syndrome

Badanta, B., González-Cano-Caballero, M., Suárez-Reina, P., Lucchetti, G., & de Diego-Cordero, R. (2022). How does confucianism influence health behaviors, health outcomes and medical decisions? A scoping review. Journal of religion and health, 61(4), 2679–2725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01506-8

Bahari, S. S., & Hassan, S. A. (2023) Culture syndrome in Asia countries: A scoping review for multicultural counseling implications. International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences, 13(12), 2222-6990. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v13-i12/20335

Cheon, H.S. (2023, December 6). South Korea says it’s overhauling its mental health care policies – but is it going far enough? Hankyoreh. https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/1119337

Garrison, Y. L., Kim, J. Y. C., & Liu, W. M. (2018). A Qualitative study of Korean men experiencing stress due to Nonprestigious Hakbeol. The Counseling Psychologist, 46(6), 786–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018798042

Gold, T.B. (1993) Problems of rapid modernization: China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. Asia: Case Studies in the Social Sciences – A Guide for Teaching. 1st edition. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315288178-51/problems-rapid-modernization-china-taiwan-korea-japan-thomas-gold

Hanson, M. (2016). The anthropology and history of medicine in Korea: Recent scholarship and new directions. Asian Medicine, 11(1-2), 1-19.

Hyojin, K. (2023, November 23). How South Korea’s academic pressure fueling youth mental health emergency. KoreaPro. https://koreapro.org/2023/11/how-south-koreas-academic-pressure-fueling-youth-mental-health-emergency/

Hyun, K. J. (1995). Culture and the self: Implications for Koreans' mental health. University of Michigan. https://www.proquest.com/docview/304206086?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses

Jarvis, J. A., Corbett, A. W., Thorpe, J. D., & Dufur, M. J. (2020). Too Much of a Good Thing: Social Capital and Academic Stress in South Korea. Social Sciences, 9(11), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110187

Jia, C.-X., & Zhang, J. (2017). Confucian values, negative life events, and rural young suicide with major depression in China. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 76(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815575014

Kahng, S. K., & Kim, H. (2010). A developmental overview of mental health system in Korea. Social Work in Public Health, 25(2), 158–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371910903070408

Kang, W.R., & Lee, J.E. (2024, October 4). South Korea’s suicide rate hits 9-year high. The Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/english/national-en/2024/10/04/3TUSDP45NNBJBNLSUYLSUGXLNU/

K-DOC (2023, July 1). Why 20s, 30s in Korea die alone at home? | Undercover Korea [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/0JQKuokS4aE?si=NWTbqe51G2URvIWU

Kim, H.J., & Song, J. (2024, February 28). Here’s why thousands of junior doctors in South Korea walked off the job. AP. https://apnews.com/article/south-korea-doctors-walkouts-patients-explained-326632dd061fc3b004b663cc761f9016

Kim, S., An, M. H., Lee, D. Y., Kim, M-G., Hwang, G., Heo, Y., & You, S. C. (2024) Impact of the early COVID-19 pandemic on suicide attempts and suicide deaths in South Korea, 2016-2020: An interrupted time series analysis. Psychiatry Investig, 21(9), 1007-1015. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2024.0089

Kwon, H. W., & Kim, J. H. (2024). Self-efficacy and life satisfaction in adolescence: Testing the presumed role of individualism–collectivism. Cross-Cultural Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971241275234

Lee, J., Wachholtz, A., & Choi, K. H. (2014). A review of the Korean cultural syndrome hwa-byung: Suggestions for theory and intervention. Asia T'aep'yongyang sangdam yon'gu, 4(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.18401/2014.4.1.4

Lee, J. (2024, September 12). South Korea to use all resources to ensure medical services during holidays amid strike. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-korea-use-all-resources-ensure-medical-services-next-month-amid-strike-2024-09-12/

Manson, M. [Mark Manson]. (2024, January 21). Why South Korea became the most suicidal country in the world [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCnvVaXEh3Y

Min, S. K. (2009). Hwabyung in Korea: Culture and dynamic analysis. World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review, 4(1), 12-21. https://www.worldculturalpsychiatry.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/03-Hwabyung-V04N1.pdf

Nagar, S. (2022, March 11) The Struggle of Mental Health Care Delivery in South Korea and Singapore. Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/the-struggle-of-mental-health-care-delivery-in-south-korea-and-singapore/

OECD. (2020). Suicide rates. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/suicide-rates.html

Oh, H., Falbo, T., & Lee, K. (2020). Culture moderates the relationship between family obligation values and the outcomes of Korean and European American college students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 51(6), 511-525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022120933682

Pang, K. Y. C. (1999). Construction of Korean Popular Illnesses: A Qualitative Analysis of Han, Hwabyung, and Shingyungshayak among Korean Immigrants. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 7(2), 134-160. https://doi.org/10.1177/105413739900700203

Park, J. (2023, December 5). South Korea unveils plan to tackle ailing mental health. The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20231205000693

Seth, M.J. (2002) Education fever: Society, politics, and the pursuit of schooling in South Korea. University of Hawaii Press.

Sethi, A. (2021). The movement for global mental health: critical views from South and Southeast Asia: Edited by William Sax and Claudia Lang. Amsterdam University Press, 2021. Anthropology & Medicine, 29(3), 348–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2021.2007755

Shin, J. H., & Yim, S. V. (2023). A Foundation for a "Cheerful Society": The Korean War and the Rise of Psychiatry. Ui sahak, 32(2), 553–591. https://doi.org/10.13081/kjmh.2023.32.553

Song, I.H. (2023, October 4) What to do about South Korea’s suicide problem. East Asia Foundation. https://www.keaf.org/en/book/EAF_Policy_Debates/What_to_Do_About_South_Koreas_Suicide_Problem?ckattempt=2

South Korea population density 1950-2024. (2024) Macrotrends. Retrieved December 10, 2024, from https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/KOR/south-korea/population-density

Sung, M., & Yeo, I.S. (2017). Mental health in Korea: Past and present. Mental Health in Asia and the Pacific: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. 10.1007/978-1-4899-7999-5_5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313932645_Mental_Health_in_Korea_Past_and_Present

Syme, K.L., Hagen, E.H. (2020) Mental health is biological health: Why tackling “diseases of the mind” is an imperative for biological anthropology in the 21st century. Yearbook Phys Anthropol, 171, 87–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23965

Tizzard, D. (2023, September 17). Korea in ten words: (3) yeoyu. The Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/opinion/2024/12/715_359356.html

Umeda, S. (2016) South Korea: Five-Year Mental Health Plan Aimed at Reducing Suicides Adopted. [Web Page] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2016-03-09/south-korea-five-year-mental-health-plan-aimed-at-reducing-suicides-adopted/.

WHO. (2022) World health statistics 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/world-health-statistic-reports/worldhealthstatistics_2022.pdf?sfvrsn=6fbb4d17_3

Mediography

Elizalde (2018, June 29). Kimchi temper. The Lenny Archive. https://www.lennyletter.com/story/korean-han-rage

[Five relationships of Confucianism table]. (2020, May 22). https://x.com/lrh_superfan/status/1263692809346875392?lang=bg

Greenberg, J. (2022, November 20) Korea’s struggle with institutionalized mental healthcare. The Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/11/113_339674.html

Jung-Kim, J. (2024) Economic Development and Democratization of South Korea. KAS Online. https://kasonline.net/economic-2/

The Korea Foundation. (2013, October 25). Window on Korean Culture - 3 Confucianism [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_bqlbSuUcDY?si=OTBi0CoCpCkhLkqD

The Korea Times [KST by The Korea Times]. (2019, November 14). SUNEUNG day: Korean students' future determined by a single exam [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/FZLwYiceIOU?si=hqK2t_n1GoFqjeKp

[Map of world suicide rates]. (2019, December 15). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suicide_rates_map.png

Nag, O.S. (2019, March 28). The culture of South Korea. World Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-culture-of-south-korea.html

[Performance of Hwanja-gut for healing]. (1903). [Photograph]. https://shamanism.sgarrigues.net/vintage-shaman-photos.html

Rose, R. [The Halfie Project]. (2023, September 11). The unexpected truth behind Korea's unhappiness (and is it affecting you?) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KxrCz8y8RXQ

Shin, M.H. (2021, May 25) Opinion: Academic elitism is such a toxic culture in Korea. The APIS Harkeye. https://theapishawkeye.wordpress.com/2021/05/25/academic-elitism-is-such-a-toxic-culture-in-korea/

Wonju, Y. (2021, August 29). Suicide death rate drops in 2013-2017: data. Yonhap News Agency. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20210829002100325

Yoon, A. (2023, November 30) South Korea’s silent struggle: Government implements new policies to curb rising rates of mental health issues. Jets Flyover. https://jetsflyover.com/10354/news/south-koreas-silent-struggle/