Living in Hell Joseon: How Chaebols Affect Youth Career Optimism in South Korea

Introduction

South Korean Economy

"Miracle on the Han River"

South Korea has undergone an “economic miracle,” emerging from the Korean War (1950-1953) to one of largest global economies in less than half a century. This is especially prominent when considering their nominal GDP was 57 times greater than their Northern counterparts in 2021 (Statista). After the Korean War, the government prioritized rebuilding the economy and important manufacturing industries by providing copious special loans to a few family owned businesses– or chaebols. These chaebols gradually expanded into other industrial sectors and concentrated heavily on exports. Exports grew from four percent of GDP in 1961 to more than 40 percent in 2016– totaling around $602.03B, which is one of the highest rates globally (WITS Data). Over a similar time period, the standard of living for most Korean citizens have improved dramatically along with literacy rates; the average annual income for South Koreans grew from $120 to more than $27,000. South Korea’s tale of poverty to prosperity, paralleled with the rise of chaebols helped solidify their role in “the narrative of South Korea’s postwar rejuvenation” (Albert).

Han River in South Korea

Han River in South Korea

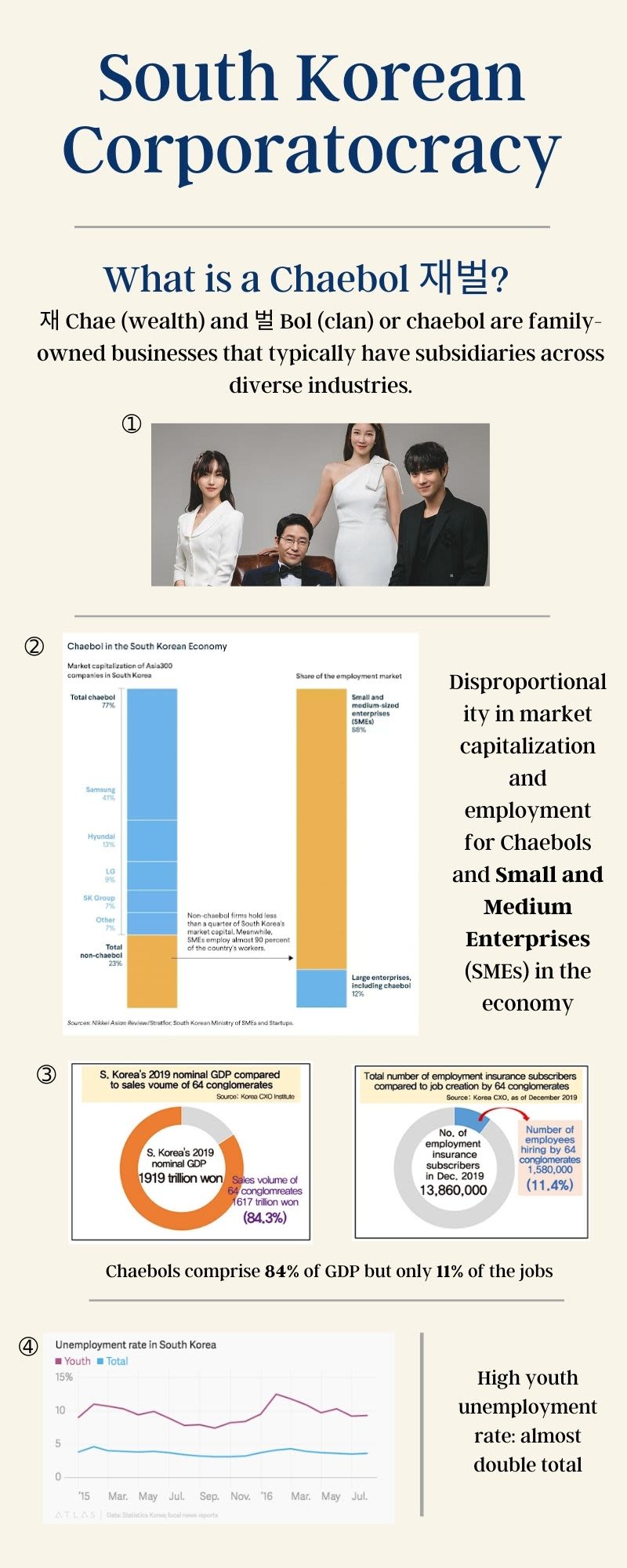

A defining characteristic of the South Korean economy is the significance of Chaebols. First, the word chaebol represents a fusion of the Korean words chae which stands for wealth and bol which means clan (Albert). Noted anthropologist Michael Prentice defines chaebol as the “conventional reference for family owned conglomerates–which refers ambiguously either to a unique South Korean organizational form or the intergenerational families that own and manage them” (249). These chaebols emerged from the disposal of ex-Japanese enterprises from their occupation of Korea before World War II (Rhyu 220). Chaebols modeled themselves after powerful Japanese conglomerates called the “Zaibatsu.” After the Korean War, foreign aid from the United States flowed into Seoul and chaebols were provided millions in special loans from the government to help rebuild the economy (Albert). For some more history, many of South Korea’s capitalists are descended from the traditional land and slave owning class– so it is no surprise that chaebols have what is describe as a “authoritarian corporate culture in which workers have been regarded by managers with varying degrees of paternalism or disdain, but rarely, if ever, as equals or even junior partners in a common enterprise.” (Ekert, 133) They normally consist of many companies under one main parent company and have advantageous relationships with the government (OECD 16).

The top four Chaebols Represented

The top four Chaebols Represented

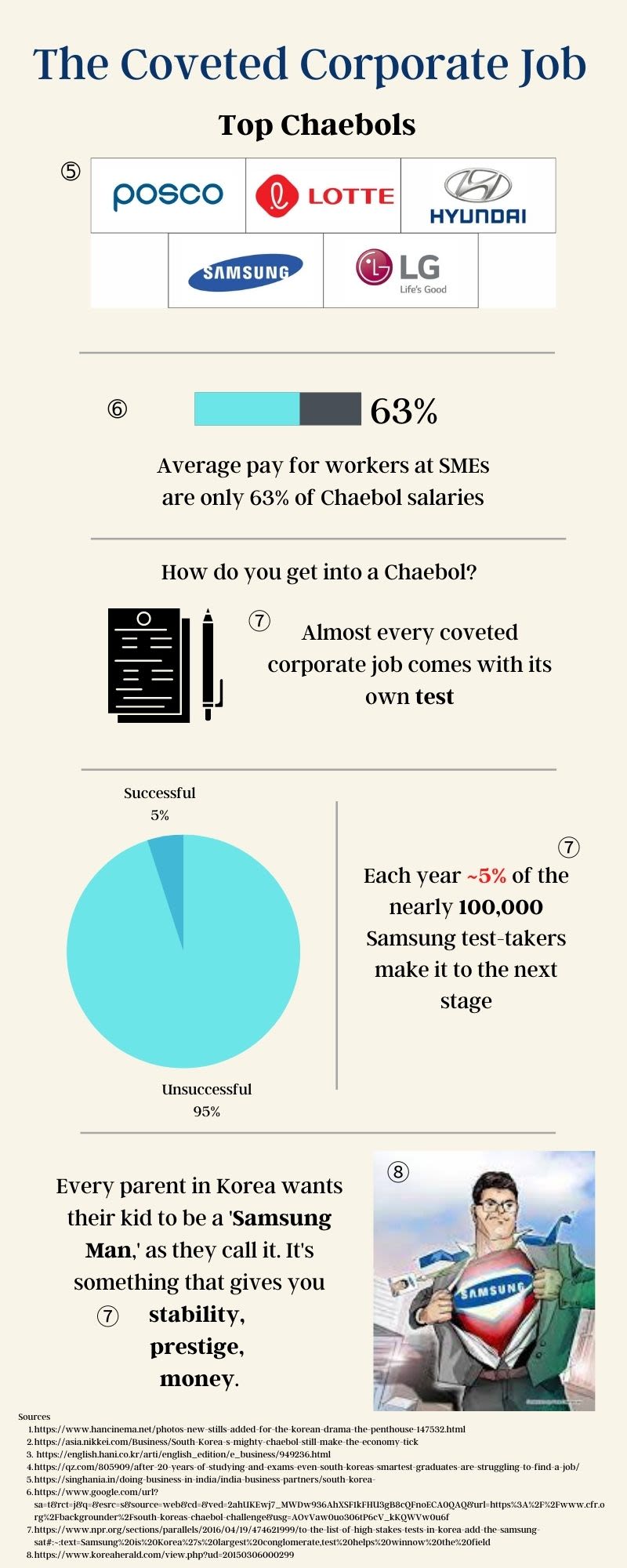

While there are more than forty chaebols, most of the economic power is concentrated in just a handful, with the top five representing approximately half of the South Korean stock market’s value. For example, amongst companies like LG and Hyundai, the largest one, Samsung is run by the Lee Family who are the second wealthiest family in Asia, and descendants of the company’s initial founder. The largest subsidiary, Samsung Electronics, has accounted for more than 14 percent of GDP in South Korea equaling 333 trillion won or approximately 255 billion in USD.

There are challenges that come with the chaebol, including numerous scandals, as well as creating a predatory environment for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the economy. Tactics employed by chaebols such as copying SME innovations make it difficult for them to thrive and grow. According to Pulse News, a Korean news outlet, “There were 1.58 million people working for the 2,284 affiliates of the 64 groups, just 11.4% of the 13.86 million people enrolled in employment insurance as of December 2019” (Pulse by Maeil Business Korea). With an abundance of economic might, it is desirable to work for a Chaebol, as the average salary at an SME is only “63 percent of that at chaebol.” These are important factors that contribute to South Korea’s growing wealth inequality, as the wage gap exacerbates, job growth slows, and the youth unemployment rate suffers (Albert). There was a large Asian financial crisis in 1997, and income disparity has widened dramatically since the financial crisis. This is demonstrated using Gini coefficients, a measure of wealth inequality within a nation, as it increased from 0.26 in 1997 to 0.31 in 2011 (Ha & Lee 6).

The Korean Education System

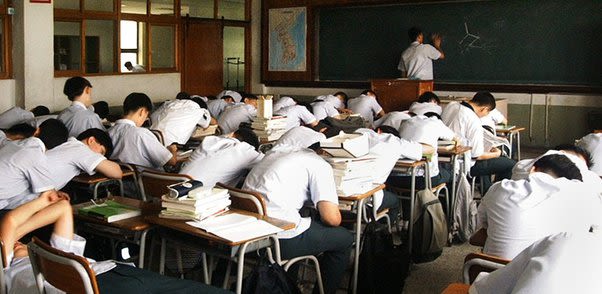

The students who enter the workforce have gone through a rigorous South Korean education system with a significant emphasis on testing. While most of the pressure is placed on high school students to take the University Entrance Exam or the Suneung, university students still feel pressure after being accepted to continue studying hard in order to stay competitive.

South Korean students taking the College Entrance Exam

South Korean students taking the College Entrance Exam

This is because the job market is scarce, and most coveted corporate jobs come with their own aptitude tests as part of the recruiting process. Meanwhile, pressure to work in one of the large conglomerates is high because of the perceived status that comes along with the increased wealth. It also seems like countless years of studying and hard work would be wasted if it did not culminate in their ability to obtain a prestigious and “cushy” corporate job. Along with the rise of social media, the dense population of the country has made it increasingly easy to compare and compete amongst themselves.

Career Optimism (CO) in the Face of Giants

As students begin entering the workforce, their levels of career optimism is an important trait that can affect their future success. Career optimism (CO) is defined as “a disposition to expect the best possible outcome or to emphasize the most positive aspects of one's future career development” (Lin). It is significant in the context of organizations as it is linked to desirable work outcomes and job satisfaction (Lin). Many things go into determining one’s level of career optimism, but some main aspects are aspirations, perceived barriers, economic opportunities, and social pressures. That is why my central research question is as follows: how does perception of Chaebols (Korean Wealth Cliques) influence South Korean University students’ career optimism? It is my contention that the perception of Chaebols diminishes South Korean student’s career optimism due to conflicting social pressure, and perceived career barriers, amongst paramount social pressure.

General Career Trajectory

The careers that exist within Korean society can be broadly categorized into White Collar and Blue Collar occupations, as they relate to office jobs and jobs that require more manual labor. Another form of categorization exists within the public and private sectors. The public sector is known to be a highly desired and stable path that one can enter after taking civil service exams. Within the private sector, there are the conglomerates as well as the Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). The career paths are not limited to this– the vocational route, as well as entrepreneurial routes as well, although not as common.

Most people in South Korea believe that a good career is working a white collar full time job permanently at a large corporation with a regular salary. The academic education path is seen as the respectable path to get there (Choi 8). The civil service exam is just as desirable, if not more. 35% of job seekers prepare for civil service examinations, which is approximately 1 in 3 job seekers (Song). Although vocational education is also available, it is not looked upon favorably. Graduates of a vocational high school are seen as “low social status and in jobs of inferior quality and lower wages, with a large gap between them and university graduates” (Choi 8). For the purposes of this paper, white collar jobs in the private sector will be a focal point, as these roles are most sought after in chaebols by South Korean University Students.

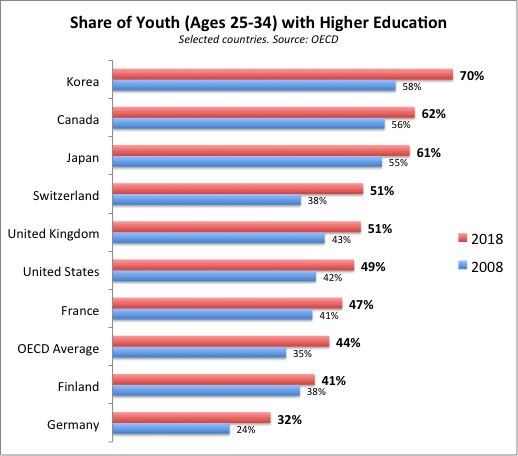

Although a corporate job is widely desired, it is not easily attainable, despite the educational achievements of Koreans. In 2014, only 13.6% of workers were employed in big firms with over 300 employees– not even excluding blue collar workers. Considering South Korea’s economic might, this is a very slim amount of workers. The OECD reports that “41.3% of employees work in micro-enterprises (i.e. those with fewer than 10 employees). Work in such enterprises can often be characterized by low wages; a precarious employment status; large gaps in social insurance coverage; and a near-total absence of trade unions.” It is clear that a large percentage of workers are not at their most desired employer while roles at large companies remain difficult to obtain. To improve their hireability for large corporations or public sector employers, many young people in Korea seek additional certifications after completing their studies (OECD). The majority of students move onto higher education after high school. While 47% of 25 to 34 year-olds in OECD countries have a tertiary qualification in 2021, in Korea, the number is 69% (OECD).

Percentage of youth with higher education. Picture from: https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2019/09/why-south-korea-cant-quit-college/

Percentage of youth with higher education. Picture from: https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2019/09/why-south-korea-cant-quit-college/

This has resulted in a more difficult job hunt for those who attend university in South Korea. The aforementioned issues also contribute to a significant amount of educational inflation, which is defined as the job applicants obtaining higher degrees for careers that have previously required lower qualifications. The result of this as described by the OECD is that, “Unemployment among youth with higher education has increased, decreasing the probability that those who attended prestigious universities would obtain a decent job.”As more students attend universities, the sheer volume of graduates leads to employers resorting to differentiating candidates through the prestige of the degree rather than the possession of it.

For South Korean university students, success in one’s career path is seemingly quite clear-cut and narrow. Given the societal pressure and what they are conditioned to believe, it is only natural that students are attracted to working for a chaebol, even as the road leading there seems more and more difficult.

South Korean University Students’ Career Aspirations

In order to better understand the career optimism of South Korean university students, one may ask, what do they want out of their careers? One of the largest job portals in Korea, Job Korea conducted a survey on the career aspirations of 1,106 South Korean university students (Pulse). It was found that an internet company called Kakao Corp. was the top workplace of choice and Samsung Electronics was a distant second. They received 15.3 percent and 9 percent of votes respectively. Another internet company, Naver, was in third place. This survey revealed that chaebols are still desirable, but with the rise in internet companies, there are more options for students.

The first reason for the greatest number of respondents (22.6 percent) their dream workplace was “the possibility to do what they want.” The second most popular concern was “…welfare policies and working environment with 22.2 percent, job security 20.8 percent and high salary 18.5 percent” (Pulse). Although it is hard to generalize these results to all university students– it is clear that freedom, and stability are important things sought after in the job market. Because big companies are very attractive to students, the recent emergence of internet companies may allow students to not weigh the possibility of working for a chaebol as heavily.

South Korean University graduation

South Korean University graduation

Career Optimism in the Face of Giants

What is career optimism and what factors go into determining it? As previously mentioned in the introduction, career optimism (CO) is defined as “a disposition to expect the best possible outcome or to emphasize the most positive aspects of one's future career development” (Lin). It is an expectation that things will work out positively in one’s career path. It is an important determinant of future success. The Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) is a framework that looks at personal and environmental factors as determinants of career optimism. The associations of career optimism were looked at in individuation dimensions– particularly in relation to parents. It was found that parental psychological control can cause “feelings of anxiety and fear, which lead to externally motivated behaviors in emerging adults.” Usually, parents tend to emphasize more extrinsic career aspects such as security and salary (Aymans et al.). Chaebols are extremely prized because they can offer such, being big companies and it is likely parents embed in kids to perceive chaebols as extremely desirable.

Because most parents pay for their children’s college tuition and living expenses, they are expected to have more influence over their children. Not to mention that South Korea’s Confucian values emphasize filial piety and obedience as an important trait. Based on this, South Korean university students can be more pressured than students in other countries to work at a large company, which have much higher barriers to entry, which can diminish their career optimism.

Applicants come out of a high school in Gangnam, southern Seoul, last October, after taking the Samsung Aptitude Test.

Applicants come out of a high school in Gangnam, southern Seoul, last October, after taking the Samsung Aptitude Test.

The Disapproval of Chaebols: Negative Social Pressure

To better understand their influence on university students, it would be useful to examine the negative perception of chaebols and why they are perceived that way. Many South Korean university students experience conflicting social pressure due to the perception of chaebols. On one hand chaebols are very attractive to work for in the eyes of society. On the other hand, these companies are known to be quite corrupt. For example, in 2016 President Park Geun Hye was impeached for using her connections for abuse of power. Lee Jaeyong, Samsung’s de facto head was convicted for bribery and embezzlement by making payments equivalent to $36.4M given to nonprofits that Park championed. He was sentenced to jail but only served five months before an appeals court suspended his sentence (BBC News). Another incident dubbed “Nut-rage” is where the heiress of Korean Air– a chaebol company– Heather Cho threw a tantrum, demanded to see the cabin crew chief, and stopped a flight from taking off because she objected to having her nuts served in their bag instead of on a plate (Finlay). The public was furious and called for her resignation. This is only the tip of the iceberg of the scandals Chaebols have been involved in. It would be reasonable for those working for chaebols– or those that aspire to work for them– to be quite conflicted and have a lower career optimism. Rising discontent is exemplified by the media now portraying chaebols as ‘unfettered predators robbing ordinary people of their livelihood’ (Choe).

There have been a number of protests against them in recent years. In order to demonstrate dissatisfaction with chaebols, activists and citizens chartered “buses of hope” to travel to Busan, a city where a female labor activist has been protesting layoffs at the conglomerate, Hanjin, by “barricading herself at the top of a giant crane.” Further, SHARPS is a group that advocates for the occupational-disease victims that worked at the largest chaebol, Samsung. The worker safety at Samsung has been a big issue with many employees falling ill and dying with illnesses such as Leukemia. They started protesting Samsung in 2015, with close to 200 protesters and had their petition to renew talks with the group supported by the International Trade Union Confederation IUTC. This network consists of “168 million workers in 156 countries'' (SHARPS). A negative opinion of the most salient companies would likely dim one's career optimism especially as the companies that are most sought after are so problematic.

The Chaebol Appeal: Positive Social Pressure

The pressure to work for a chaebol or other large conglomerates still remains high. The stability/ job security, salary, and prestige still draw many applicants. The wealth gap can be exemplified as the salary at a SME is only 63% that of a Chaebol as previously mentioned (Albert). Tenure also tends to be shorter at SMEs, as they rely on fixed term contracts which allow firms to be less committal to hires in the long run. “The workers in the smaller sizes of firms have shorter average job tenure, the average job tenure for workers in firms with less than 5 employees being only 20 per cent of that for the workers in large firms'' (Ha and Lee 25). Working at Chaebols is still seen as a Status symbol, and the perspectives from the older generation still influence university students. "Every parent in Korea wants their kid to be a 'Samsung Man,' as they call it. It's something that gives you stability, prestige, and money. You can find a good apartment or a wife if you are a Samsung Man…” (Hu). With parental expectations, and attractive features, a university student is socialized to desire a job at a chaebol.

Part of the appeal can be attributed to the “Dynastic Aura,” which is extremely important to the perception of chaebols. In Prentice’s work, he explores how managers at a Chaebol were attracted to work for them from his first-hand experience within one of the companies. He refers to the company using the pseudonym “Sangdo Group '' which is an industrial steel and metal Chaebol with many subsidiaries. Dynastic aura describes how “Multi-generational corporate dynasties in South Korea are imbued with a kind of class-celebrity aura, through their super-elite lifestyles, secretive private lives, and occasional tabloid stories…” They are viewed as very powerful in South Korean pop cultures. In many Korean dramas, the chairman has the ability to enact drastic change with just one phone call (Prentice 252). Another common trope depicts modern Cinderella stories of a rich male with generational wealth coming from a powerful chaebol family falling in love with a poor girl. They are highly visible in popular culture and the media, which can contribute to their relevance when it comes time for university students to apply to jobs.

All this to say Chaebols have a certain aura of prestige and social relevance that attract people to want to work for them. After people become insiders, they become disillusioned with the reality, understanding that the chaebol was not as powerful as some had thought. So how does it relate to a student’s career optimism? Well, it can increase if they were to get into a chaebol, because of all the perceived benefits and certain image that it brings. However, I postulate that it overall diminishes the career optimism of university students who are applying to jobs because popular culture makes it “cool” to work for them when the grim reality is such a high barrier to entry.

Common portrayal of a chaebol heir in a popular Korean drama, "What's Wrong With Secretary Kim?". Description from Youtube video: "Can you be so self-absorbed that you have no idea what’s truly going on around you? Lee Young Joon (Park Seo Joon) is vice president of his family-owned company, Yoomyung Group. He is so narcissistic that he doesn’t pay attention to what his trusty secretary, Kim Mi So (Park Min Young), is trying to tell him most of the time."

Violent clash during rally at Hanjin Heavy: Police shoot water cannons to disperse demonstrators Saturday night near Yeongdo Shipyard of Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction, Busan, during an overnight protest organized to support a female labor activist staging a sit-in on a giant crane for more than 180 days. / Korea Times photo by Lee Sung-deok

Violent clash during rally at Hanjin Heavy: Police shoot water cannons to disperse demonstrators Saturday night near Yeongdo Shipyard of Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction, Busan, during an overnight protest organized to support a female labor activist staging a sit-in on a giant crane for more than 180 days. / Korea Times photo by Lee Sung-deok

21 November 2018, some 128,277 workers at 109 KMWU workplaces joined a strike against government failure to challenge the dominance of industrial conglomerates know as chaebols.

21 November 2018, some 128,277 workers at 109 KMWU workplaces joined a strike against government failure to challenge the dominance of industrial conglomerates know as chaebols.

How Chaebols are portrayed in the media

How Chaebols are portrayed in the media

The heir of Samsung, Korea's most powerful chaebol

The heir of Samsung, Korea's most powerful chaebol

“Why is it becoming harder to get a decent job?”

Declining Job Prospects

Perceived barriers are very relevant as it relates to career optimism. They have been shown to have a negative effect on career optimism, as studies have found support for a relationship between “greater perceived career barriers and the diminished ability to pursue goals” (Wu). In 2017, the average duration between graduation and starting a first job was almost a year. This is unfavorable compared to other OECD countries such as “Australia, Canada, Germany and the United States, but are comparable or lower than durations observed in Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom in 2011 (Quintini and Martin, 2014[25]).“ Youth employment and education in Korea” (OECD). It is more difficult for South Korean University students to find employment after graduation than in other countries.

Another significant barrier is the field of study mismatch between academic majors and jobs. Amongst OECD countries, the number is 46.8 percent, being ten percentage points higher in Korea and the fifth highest. Education inflation has also led to rising Perceived barriers are very relevant as it relates to career optimism. They have been shown to have a negative effect on career optimism, as studies have found support for a relationship between “greater perceived career barriers and the diminished ability to pursue goals” (Wu). In 2017, the average duration between graduation and starting a first job was almost a year. This is unfavorable compared to other OECD countries such as “Australia, Canada, Germany and the United States, but are comparable or lower than durations observed in Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom in 2011 (Quintini and Martin, 2014[25]).“ Youth employment and education in Korea” (OECD). It is more difficult for South Korean University students to find employment after graduation than in other countries.

Another significant barrier is the field of study mismatch between inadequate skills even amongst university graduates. Amongst OECD countries, the number is 46.8 percent, being ten percentage points higher in Korea and the fifth highest. The top three fields of study were Engineering, manufacturing and construction, Social sciences, business and law, and Humanities and arts with the percentages being 27.4%, 22.3%, and 21.4% (136). This points to a larger systemic issue of the education to labor pipeline. Education inflation has also led to rising overqualification (OECD). According to a 2018 report, around one in five in the 25 to 29 age group were unemployed. This is one of the highest ratios in the developed world (CNA Insider). Still, there is a complaint of a lack of skill even amongst university graduates. “Representatives of the Federation of Korean Industries complained about a lack of abilities that have been called

in other countries ‘higher-order’, like problem-solving and the ability to perform well in groups.” Chaebols also are scaling back hiring. The declining job prospects in the economy, perpetuated by chaebols play a key role in diminishing the career optimism of South Korean university students due to an increase in perceived barriers.

Korean Students Graduated from Korea University

Korean Students Graduated from Korea University

How competitive is it to get into a chaebol?

Competition is an important contextual influence to examine within the context of perceived barriers to employment for university students, as it diminishes career optimism. The job market for corporate jobs is competitive as previously mentioned. This has to do with the expectation of success after a life-long buildup of intense education. Steger explains, “After a lifetime of cram schools and testing, the pressure to get into a prestigious Korean company remains high and is expected.” Young Koreans entering the workforce face a dilemma of disliking the chaebols yet competing to work for them due to societal and familial pressure. When looking into the hiring rate for entry level applicants, 200,000 people took Samsung’s test in 2014, competing for 14,000 jobs (Steger). Only about 5 percent of the nearly 100,000 Samsung test-takers move on to the next stage of the hiring process (Hu). And many of the Chaebol companies have scaled back hiring since the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only does South Korea have one of the most highly educated populations on the planet, but even the top students in Korea have a hard time getting in. This is especially problematic as youth unemployment is a big issue, not to mention a third of the people that are unemployed have an undergraduate degree (Sharif).

More than 2,000 engineers and bachelor degree holders graduating from universities attend Global Samsung Aptitude Test (Source: Samsung)

More than 2,000 engineers and bachelor degree holders graduating from universities attend Global Samsung Aptitude Test (Source: Samsung)

In June 2019, “Statistics Korea'' reported that “453,000 people from the ages of 15 to 29 were unemployed, resulting in a 10.4% youth unemployment rate.” This was one of the highest youth unemployment rates in the country over the past two decades. In a street interview done by Asian Boss in 2020, they interviewed local Koreans on the streets of Seoul. One twenty-three-year-old interviewee said his older friends are looking for jobs and even though they are very qualified they can’t seem to get into big companies, and have a hard time getting into mid-sized companies as well. “These days even if you have the highest qualification, it’s still difficult to get a job. I get stressed from all the pressure.” Some university students also feel a lack of options not only because blue collar jobs are not respected and compensated well but also because the industries and markets are already saturated. “This society forces you to compete so much. Growth was competition. We competed and competed and the best one survived,” says Kim Jon-hun, a student at Donguk University. It is likely that the career optimism of university students would decrease based on their perceived barrier of competition, even though they continue to pursue their degree (Williams).

This file photo, taken Aug. 30, 2022, shows people crowded at a job fair in the southern city of Busan. (Yonhap)

This file photo, taken Aug. 30, 2022, shows people crowded at a job fair in the southern city of Busan. (Yonhap)

Relevant Societal Values

When looking at career optimism of South Korean university students, it may be useful to examine the social values held strongly. In an article by BBC, Ko Eun Suh is an 18-year-old student that is interviewed and says "If you want to be recognised, if you want to reach your dreams, you need to go to one of these three universities. Everyone judges you based on your degree and where you got it" (Sharif).

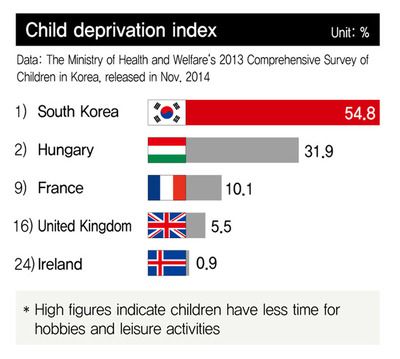

Dr. Kim Tae-Hyung, a psychologist working in Seoul says the pressure to get into a good university and get a good job starts young. There is a very narrow row to “success,” as there is an extreme level of stress around the university application process. Many young people aim for the Sky- South Korea’s most prestigious universities Seoul, Korea, and Yonsei. “They are seen as the Harvard and Yale, or Oxford and Cambridge, of South Korea.” But only 2% of high school graduates can attend. From childhood, students prepare academically for the Suneung, the university entrance exams, which determine their chances at attending SKY institutions. Further, these universities are known for their connections to getting jobs at an influential Chaebol. The “Hagwon” or “cram school” industry is booming, with more than 80% of all Korean children attending for extra lessons (Sharif). The national exams are seen as the culmination of their lifetime of study– placing a heavy importance on their grades.

He says "children are feeling nervous from a very young age. Even first-year elementary students talk about which job pays the most." A sociology professor at Yonsei University, Lee Do-hoon believes that the country is obsessed with educational achievement. It is concerning that in South Korea, suicide is the leading cause of death for young people between 10 and 30 years old, while it is the second cause of death globally. The suicide rate also continues to increase, unlike almost all other OECD countries. Prof. Lee speculates "I think the high suicide rate is being driven by an increasing gap between the lack of employment opportunities, and students' own expectations of success. There is also a lack of coping strategies to handle the stress." Based on all this, students may suffer extreme pressure to get a specific type of job and diminish their career optimism out of strong societal pressure (Sharif). One high school student says, “But if I think about my parents’ support, expectations and how much they’ve invested in all of this, I can’t betray them.” The parental pressure is paramount. The job search is just a continuation of this. One can see Korean student life as a “culture of endurance” as the amount of effort required to maintain societal expectations increases.

South Korean society is more conformist. It is notable that South Korea is a country that has never experienced a social revolution (Eckert 133). Michele Gelfand, a cultural psychologist of the University of Maryland conducted a survey in 33 countries that looked at 6,800 people. Each country got a “tightness” figure that reflected the number of social norms and “… how strictly they were enforced. “A smaller range of behaviors were seen as acceptable in a tight culture. South Korea was one of the tighter countries and it is no surprise that there is less freedom to deviate from the norm (Marshall). If the culture wasn’t as conformist, it is likely there would be less of an expectation to succeed academically. It makes sense that students would feel so much pressure to succeed in very socially constructed areas such as getting into prestigious universities and getting good jobs.

Logos of the top three universities in South Korea

Logos of the top three universities in South Korea

South Korean students studying

South Korean students studying

Children in Korea study longer hours and have less free time for other activities

Children in Korea study longer hours and have less free time for other activities

Students asleep in a classroom

Students asleep in a classroom

Hell Joseon

This “culture of endurance” has led to widespread disillusionment with Korean society. “Hell Joseon” is a popular metaphor that young people have been using to describe the difficulties of living in Korea, including obtaining careers. ‘Joseon’ refers to a dynasty where Koreans suffered a lot and social hierarchies controlled much of people’s fate.

There is a growing sense of desperation, where young people are working as hard as they can, only to get left behind. This term seems like a reaction against the struggles of high wealth inequality, education inflation, long working hours, and record high youth unemployment they are facing (Schoonhoven). Later in life, “The high cost of living and limited job opportunities are driving many young people to reject traditional life paths such as relationships, marriage, and having children.” This is referred to as the “sampo generation” which means “three give-up.” But as they are giving up on many more things, such as home ownership and social life, it is now the ‘n-po generation’ with ‘n’ standing for numerous sacrifices. For those who are lucky enough to get jobs, they have to contend with long work hours. Those who are born into wealth, including families of Chaebols, who are so often portrayed in the media, get to "bypass the entire hellish system" (Denney). Some of these sacrifices come from a place of prioritizing other areas of success. Young people are stressed from the weight of competition and expectation and are losing hope for their futures. Their giving up of some basic human desires points to the failure of the current system to provide happiness through effort– as family background has a greater influence on one’s success. It will be interesting to see whether this termination of effort and optimism will serve as a point of inflection before massive social upheaval. Will the young people of South Korea break free from conformity and reshape the system? And will South Korea be able to maintain its global power?

Painting of a South Korean classroom in the latter Joseon Dynasty (around 1745-1806) Credit:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seodang,_Chosun.jpg

Painting of a South Korean classroom in the latter Joseon Dynasty (around 1745-1806) Credit:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seodang,_Chosun.jpg

A Job Korea survey found that nine out of 10 young workers and college students empathize with the term “Hell Joseon.” Participants included 1,800 office workers and 1,300 university students. Looking at college students specifically, 66.3 percent cite the job crunch as the foremost reason they agree to the term (Choi). The limited translation of effort to social mobility If the general sentiment of young people is of agreement for Hell Joseon, it can be safe to say that university students do not have a rosy picture of their future. Along with their general life optimism, students' career optimism is especially likely to be lowered. The perceptions of chaebols and how their role in perpetuating wealth inequality in the country are likely to cause a similar effect.

Conclusion

As South Korea continues to receive global admiration and for their entertainment and exports, the problems faced by ordinary South Korean students are not as visible to outsiders. Based on social pressure, perceived barriers, and many more factors in which Chaebols are involved, it is unlikely that most South Korean university students are feeling optimistic about their future careers. It is clear that young people are dissatisfied with the status quo and the lifestyle of all work and no play is unsustainable. While jobs at Chaebols are still attractive, the emergence of internet companies will allow young students more opportunities and diminish the influence of Chaebols’ on career optimism. While my paper looks at South Korean university students as a whole, more research is needed to understand how students are affected differently, especially in regard to the requirement for men to serve for at least two years in the military. There is further room for comparison within other Asian countries such as China, Japan, and etc. While every society has its issues, South Korea’s culture of effort has created a double-edged sword as students struggle for success. Above all, it is clear that structural change needs to occur for the wellbeing of South Korea’s future generations.

Infographic

Works Cited

Albert, Eleanor. “South Korea’s Chaebol Challenge.” Council on Foreign Relations, 4 May 2018, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/south-koreas-chaebol-challenge.

Aymans, Stephanie C., et al. “Gender and Career optimism—The Effects of Gender‐specific Perceptions of Lecturer Support, Career Barriers and Self‐efficacy on Career Optimism.” Higher Education Quarterly, vol. 74, no. 3, Wiley, Dec. 2019, pp. 273–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12238.

BBC News. “Park Geun-hye: South Korea’s Ex-leader Jailed for 24 Years for Corruption.” BBC News, 6 Apr. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-43666134.

Choe, Sang-hun. “South Korean Family Conglomerates Pressured.” New York Times, Sept. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/09/14/business/global/south-korean-chaebol-under-increasing-pressure.html. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

Choi, Sung-jin. “90% of Young Koreans Sympathize With 'Hell Joseon'” The Korea Times, 2 July 2016, www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2016/07/116_208441.html. Accessed 14 Nov. 2022.

CNA Insider. “Hell Joseon: The Price of Happiness in South Korea | Deciphering South Korea - Ep 3 | Documentary.” YouTube, 10 Sept. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1zoyyj0jMg.

Denney, Steven. “Is South Korea Now ‘Hell Chosun’?” The Diplomat, 25 Sept. 2015, thediplomat.com/2015/09/is-south-korea-now-hell-chosun.

Eckert, Carter J. “The South Korean Bourgeoisie: A Class in Search of Hegemony.” Journal of Korean Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, Project Muse, 1990, pp. 115–48. https://doi.org/10.1353/jks.1990.0010.

Finlay, Mark. “Nutgate: How the Serving of a Preflight Snack Delayed a 2014 Korean Air Flight and Led to a Jail Sentence.” Simple Flying, 2 July 2022, simpleflying.com/korean-air-nutgate-story.

Ha, Byung-jin, and Sangheon Lee. “Dual Dimensions of Nonregular Work and SMEs in the Republic of Korea.” International Labor Office, 2013, ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_232510.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov. 2020.

Hu, Elise. “To the List of High-Stakes Tests in Korea, Add the Samsung SAT.” NPR.org, 19 Apr. 2016, www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/04/19/474621999/to-the-list-of-high-stakes-tests-in-korea-add-the-samsung-sat.

Korea, Rep. Trade Balance, Exports, Imports by Country 2016 | WITS Data. wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KOR/Year/2016/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/by-country.

Lin, Xinqi, et al. “The Antecedents and Outcomes of Career Optimism: A Meta-analysis.” Career Development International, vol. 27, no. 4, Emerald, Aug. 2022, pp. 409–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/cdi-01-2022-0023.

Marshall, Michael. “People in Threatened Societies Are More Conformist.” New Scientist, 26 May 2011, www.newscientist.com/article/dn20510-people-in-threatened-societies-are-more-conformist.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Korea Overview of the Education System (EAG 2022).” Education GPS OECD, 2022, gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=KOR&treshold=10&topic=EO#:~:text=Education%20GPS%20The%20world%20of%20education%20at%20your%20fingertips&text=In%20Korea%2C%2069%25%20of%2025,on%20average%20across%20OECD%20countries. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT. OECD Reviews of Tertiary Education Korea. OECD, 2009, www.oecd.org/korea/38092630.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

Park, Hyun-jung. “75% of Younger S. Koreans Want to Leave Country.” Hankyoreh, Inc, 30 Dec. 2019, www.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/922522.html. Accessed 14 Nov. 2022.

Pulse. “Kakao Top Workplace Choice for Jobseekers, Naver Third After Samsung Elec.” Pulse by Maeil Business Korea, Aug. 2021, pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?sc=30800028&year=2021&no=754682. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

Pulse by Maeil Business Korea. “Samsung, Hyundai Motor, SK, LG Behind Half of Corporate Sales, Payroll in Korea.” Pulse by Maeil Business Korea, June 2021, pulsenews.co.kr/?year=2021. Accessed 10 Dec. 2022.

Rhyu Sang-young. “The Origins of Korean Chaebols and Their Roots in the Korean War.” The Korean Journal of International Studies, Korean Association of International Studies, Dec. 2005, https://doi.org/10.14731/kjis.2005.12.45.5.203.

Schoonhoven, Johan. “Hell Joseon’.” Lund University Lund University Publications, 2017, lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8923985&fileOId=8923986. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

Sharif, Hossein. “Suneung: The Day Silence Falls Over South Korea.” BBC News, 26 Nov. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46181240.

SHARPS. “A Year Into Sit-in, SHARPS Urges Samsung’s Heir Lee Jae-yong to Reinitiate Dialogue.” GoodElectronics, 30 June 2017, goodelectronics.org/a-year-into-sit-in-sharps-urges-samsungs-heir-lee-jae-yong-to-reinitiate-dialogue.

Song, Hyun- jin and Gongdan Tech Academy. “한국의 가장 흔한 직업 ‘취업준비생’, 노량진 취준생이 살아가는 이야기.” www.donga.com, 19 Jan. 2016, www.donga.com/news/Life/article/all/20160119/75999326/2.

Statista. “GDP Comparison Between South and North Korea 2010-2021.” Statista, 23 Aug. 2022, www.statista.com/statistics/1035390/south-korea-gdp-comparison-with-north-korea.

Steger, Isabella. “After 20 Years of Studying and Exams, South Korea’s Smartest Graduates Struggle to Find a Job.” Quartz, 21 July 2022, qz.com/805909/after-20-years-of-studying-and-exams-even-south-koreas-smartest-graduates-are-struggling-to-find-a-job.

Williams, Mike. “‘Hell Joseon’ and the South Korean Generation Pushing to Breaking Point.” ABC News, 30 Jan. 2020, www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-30/south-korea-hell-joseon-sampo-generation/11844506.

Wu, Ben Hao. The Role of Career Optimism and Perceived Barriers in College Students’ Academic Persistence: A Social Cognitive Career Theory Approach. The University of Southern Mississippi, 2018.

Mediography

https://youimg1.tripcdn.com/target/100i1f000001gp4ip90F7.jpg?proc=source%2Ftrip

https://miro.medium.com/max/1200/1*5Xn5j5HLFvyNWzCSyHyWag.jpeg

https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2019/09/why-south-korea-cant-quit-college/

https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20160923000424

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2011/07/117_90600.html

https://www.industriall-union.org/korean-workers-down-tools-in-national-strike-for-chaebol-reform

https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20170113007300320

https://www.tellerreport.com/life/2021-03-15-%0A---i-can-t-get-a-job-even-if-i-have-a-high-degree-of-education--%0A--.r1LTfFq2Q_.html https://www.sggpnews.org.vn/business/samsung-holds-aptitude-test-for-potential-recruits-87260.html

https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220916000088

http://en.koreaportal.com/articles/4922/20151125/south-korea-students-overseas.htm

https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/663037.html

https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-c4bb07a350568c4ac8d471539343cefd

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seodang,_Chosun.jpg