When Traditions Kills

The Cultural Foundations for Femicide in Italy

Italy's Femicide Crisis

The most dangerous place for an Italian woman is in her home. At the mercy of her husband, or even her son, gender-based violence is something of an epidemic in Italy. Femicide, defined by the United Nations as the intentional killing of women because they are women, has become both a social tragedy and a public crisis in the small Mediterranean country. In 2023 alone, over 100 Italian women were killed by intimate partners or family members. For many women, domestic spaces remain unsafe. Their homes, their families (including their children) and their communities bear witness to the continued gendered violence that places women in constant states of danger. Yet, little is done to protect these women. These statistics underscore the deep cultural and institutional failures that have allowed femicide to persist despite growing awareness. In recent years, there has been widespread debate about the cultural, legal and institutional structures in Italy that allow for the continued persistence and proliferation of the violence against women. To answer this question, it is first necessary to refer back to Italy’s long standing historical and cultural roots that have shaped gender relations and the social perceptions of women’s roles. This project investigates why femicide persist in Italy despite public visibility, activism, and legislative reforms. More specifically, it asks: How do Italy’s cultural, religious, legal and institutional systems sustain the conditions that enable femicide, and what structural changes are necessary to meaningfully address gender-based violence?

To answer this question, it is first necessary to refer back to Italy’s long standing historical and cultural roots that have shaped gender relations and the social perceptions of women’s roles. I argue that femicide in Italy is not a series of isolated incidents, but a structural phenomenon produced through the interaction of deep patriarchal norms, institutional distrust, and legal practices that minimize or excuse male femicide. By tracing these cultural and religious foundations alongside legal cases, ethnographic court research, media analysis, and comparative European data, this project adopts an interdisciplinary approach grounded in anthropology, gender studies, history, sociology, and feminist legal theory.

The Catholic Church

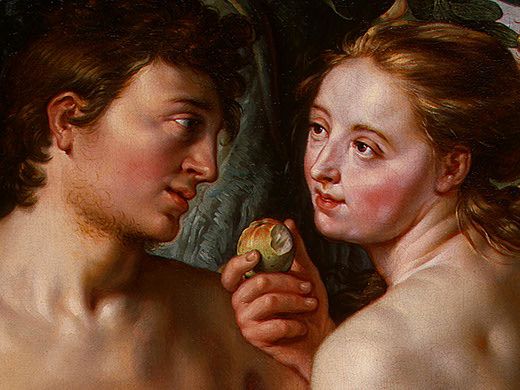

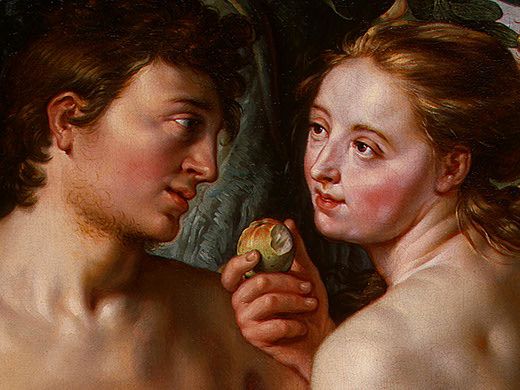

The conversation of femicide in Italy cannot be had without first acknowledging the historical and cultural institutions that have shaped gender relations and the social perception of women’s roles. Italy’s patriarchal structures are heavily influenced by its proximity to the Catholic church and the gender binary that it has created with centuries of influence not just in Italy, but the globe. The gender binary created by the church posits a system of governance, culture, and social institutions that position women as inferior to men based solely on their alleged physical closeness to god. At the risk of simplifying a long, and arduous history of Catholic misogyny and chauvinism with a few verses, Biblical interpretations and Church doctrine have long upheld male authority. Many notable and widely influential Christian theologians cite Genesis 2:22. “And the rib that the Lord God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man”. Thus, a woman’s existence, her being, and her humanity became reliant on man. A woman is forever indebted to man for her life and her physical body. In turn, her physical body partly belongs to him. There are a number of other passages that are frequently cited when referring to gender roles, a women’s place in the home and proposed relations and dynamics between men and women (Crivellone 2020, 3–5; Accati 1995, 241–44). These religious narratives have long functioned as political technologies of gender control, linking women’s bodies to systems of labor, morality, and social institutions. Such frameworks exemplify what Pierre Bourdieu calls symbolic violence: the internalization of social hierarchies through cultural and religious norms that appear natural and unquestioned (Bourdieu 2001). This helps explain why patriarchal dominance in Italy has historically been understood not merely as social convention but as divinely sanction truth.

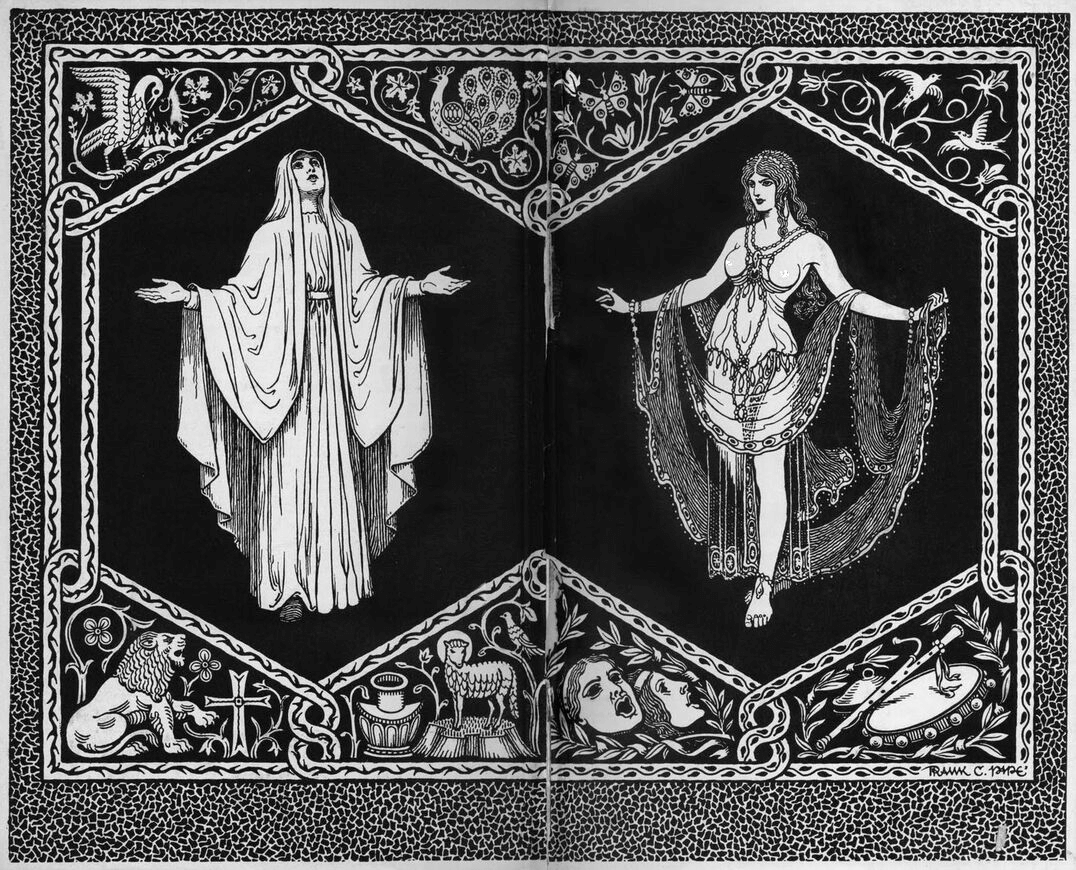

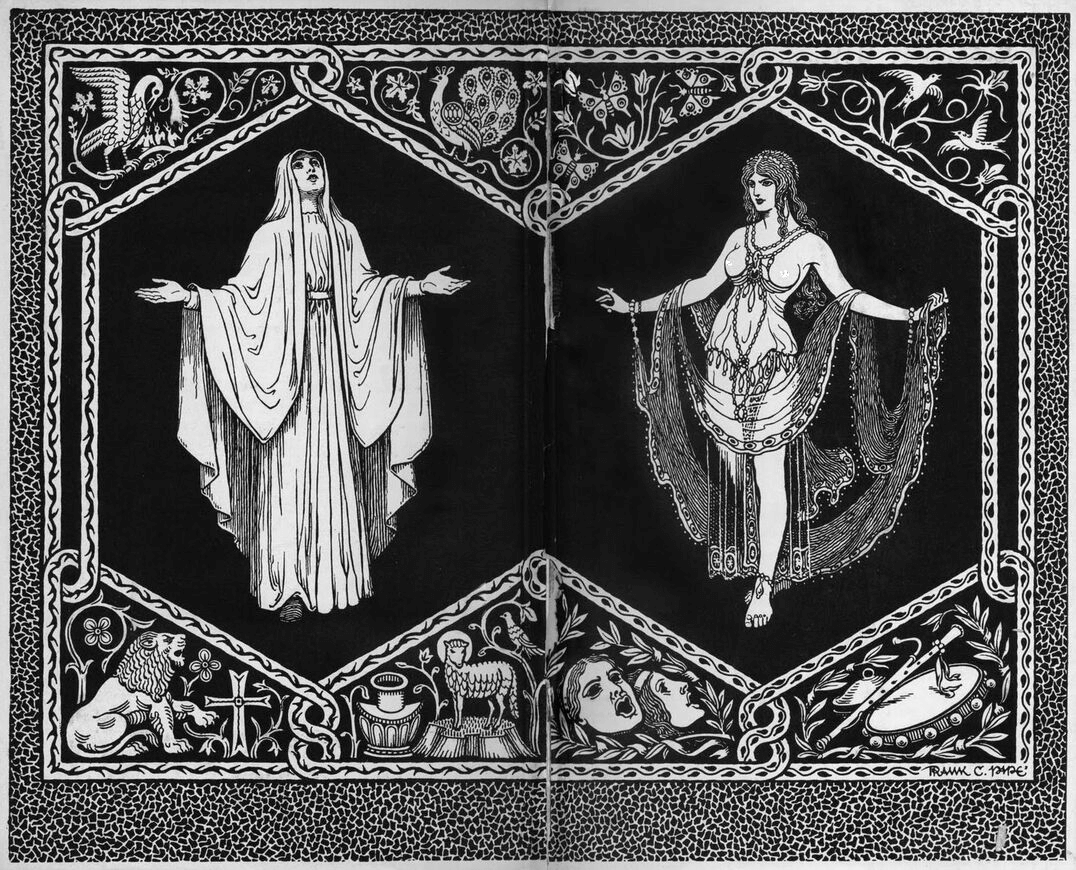

The Church’s authority has long extended beyond religion, shaping cultural and moral expectations that define women through motherhood, purity, and obedience. By sanctifying the patriarchal family and presenting male dominance as divinely natural, the Church helped embed gender hierarchies within both law and daily life. Divorce, contraception, and abortion were all heavily restricted under its influence, leaving women legally and morally bound to their husbands, even in violent relationships (Crivellone 2020, 7–8). Culturally, Catholic ideals such as the Madonna-whore dichotomy continue to divide “good” and “bad” women, legitimizing control and punishing autonomy (Accati 1995, 253–55). This moral framework transforms male authority into a sacred duty and female submission into virtue, making gender-based violence appear as a tragic but socially understandable outcome. In this way, Italy’s nearness to the Church sustains the patriarchal structures that enable femicide to persist (Accati 1995, 249; Crivellone 2020). Feminist anthropologist Rita Laura Segato suggests that deeply rooted patriarchal order shape not only interpersonal relations but the very organization state institutions, producing patriarchal political orders that structure women’s vulnerability across generations (Segato 2016). These historical legacies therefore extend directly into contemporary legal, social, and cultural systems that regulate gender and violence in Italy.

The Renaissance

Italy on the global stage is not known for its alarmingly high femicide rates or even gendered violence. It is however known for its artistic and cultural production, especially as it relates to the Renaissance. Another one of Italy’s major cultural and historical influences that translates widely to its contemporary structures and institutions, the Renaissance is marked as a transition from the Middle Ages to modernity. It was a "rebirth" of interest in classical Greek and Roman culture, leading to significant achievements in art, science, literature, and exploration. Renaissance art often depicted the idealized women’s chastity, or women in the Bible who acted as symbols for various virtues that women were supposed to subscribe to. For example, The Virgin Mary, whose alters can still be found on arguably every street corner in Italy in what they call Madonelle’s or Edicole Sacre’s, is one of the Renaissance’s most notable figures (National Catholic Register 2024). The church’s influence and the desire for women to be made in the image of the Madonna, The Virgin Mary becomes both the model and the instrument of power, women’s real agency is subsumed into an idealized, desexualized, and sacred motherhood (Accati 1995, 247–48). The Renaissance also brought with it the revitalization and resurgence of literature and philosophy of past eras that often-presented women as emotional, fragile, and intellectually inferior, which sustained their exclusion from public life (Kelly 1977, 21–24).

From an art, historical, and cultural studies perspective, such imagery operates a as form of gendered representation that shapes collective perception. Representation is not merely a reflection of reality but an active process of meaning-making that reinforces social hierarchies. Renaissance depictions of idealized womanhood therefore serve as cultural scripts that continue to inform Italian gender norms today. While there are a myriad of other institutions and cultural or historical influences that speak to Italy’s persistent patriarchy and gendered violence, the focus of this paper will rely mostly on the influence of the Catholic Church and the Renaissance. These deeply rooted cultural and religious legacies have shaped the way Italians view women, justice, and authority. Attitudes that continue to influence modern institutions and public perceptions. By situating these historical frameworks within interdisciplinary scholarship, including anthropology, history, and feminist theory its clearly demonstrated how patriarchal values are reproduced across time, becoming embedded in Italy’s contemporary legal and social institutions.

Femicide in Italy

Femicide in Italy is both a political and social crisis that reveals the persistence of gender asymmetries and the state’s failure to adequately protect women. Male violence against women is a deeply rooted phenomenon that transcends class and status, reflecting structural inequalities within Italian society. The murder of Giulia Cecchettin in 2023 served as a political flashpoint, forcing public recognition of femicide as a national issue rather than a private tragedy. The absence of legal specificity obscures the gendered nature of these crimes and allows the state to treat them as isolated acts of violence rather than symptoms of systemic inequality. Statistical evidence reinforces this gap: a woman is killed every three days in Italy (Ministero dell’Interno, 2023; EDJNet, 2023), and nearly 87 percent of female homicide victims are murdered by an intimate partner (EIGE, Measuring Femicide in Italy, 2021; IMPRODOVA, 2023; UNODC, 2019), far above the European average of 29 percent (UNODC, 2019; Eurostat, 2018). Most femicides occur in private spaces, with 55 percent taking place in the couple’s home and 22 percent in the victim’s own home (Ministero dell’Interno, 2021; EURES, 2020; ISTAT, 2018), underscoring the domestic roots of this violence. While right-wing parties in power emphasize punitive and securitarian approaches, lasting progress requires structural and cultural reform addressing gender hierarchies, education, and socialization rather than merely harsher penalties.

The analytical framework guiding this project uses a definition posited by Russel and Radford (1992) and UN Women as the gender motivated killing of women. A form of violence not rooted in interpersonal conflict but in structural systems of inequality. Likewise, patriarchy is used in Sylvia Walby’s sense as a network of legal, cultural, economic, institutional arrangements that systematically privilege men and subordinate women, reinforcing the patriarchal political orders that make gendered violence both predictable and socially reproduced. These dynamics speak to a sort of structural violence in which institutions embed harm into everyday life by rendering certain populations, women in this case, more vulnerable to injury, neglect and even death. Understanding femicide through these frameworks makes clear that the absence of legal specificity in Italy, the high proportion of intimate-partner killings, and the concentration of violence in domestic spaces are not isolated phenomena but interconnected outcomes of Italy’s cultural, religious, legal, and social structures. These definitions and theoretical lenses provide the foundation for interpreting the statistical data, case studies, court ethnography, and media analysis that follow.

Recent Femicide Cases

Several recent femicide cases in Italy have evoked national outrage and renewed debates about patriarchy, justice and gender-based violence. Together these cases reveal not only the extreme brutality of femicide in Italy but also the persistent societal and institutional patterns that normalize gendered violence and undermine justice for women.

Giulia Cecchettin

One of the most shocking was the murder of 22-year-old university student Giulia Cecchettin who was brutally stabbed more than twenty times by her ex-boyfriend, Filippo Turetta, just days before her graduation. Her body was later found near a lake in the Veneto region, wrapped in black plastic bags. The brutality of the killing, and Cecchettin’s young age sparked widespread protests and public condemnation of Italy’s patriarchal culture, with her family calling for a “cultural revolution” to address systemic roots of male violence (The Guardian, 2024; GC Human Rights, 2023).

Giulia Tramontano

Another widely publicized case was that of Giulia Tramontano, a 29-year-old pregnant woman murdered by her fiancé Alessandro Impagnatiello, who poisoned her and stabbed her multiple times before attempting to burn her body. Her death intensified public pressure for stronger laws against intimate parter violence and femicide (Euronews, 2023).

Antonia Gozzini

The Antonia Gozzini case (2020) further underscored systemic failures when the 80-year-old man was initially acquitted after killing his wife, Cristina Maioli, by bludgeoning her with a rolling pin and slitting her throat, with the court citing a “raptus” or delirious jealousy as justification. The ruling provoked widespread outrage and was seen as emblematic of the Italian justice system’s tendency to minimize male violence through cultural excuses (Newsweek, 2020; Yahoo News, 2020).

The Mafia

Social attitudes toward gender and violence in Italy remain conflicted, as progress toward equality clashes with enduring traditional values and widespread distrust in state institutions. Many Italians express limited faith in law enforcement and the judicial system particularly in rural and southern regions where corruption and social stigma remain prevalent. Particularly, the historical influence of the Mafia and its codes of silence, or omertà, further deepen community mistrust of the authorities. The history of the Italian mafia began in the southern regions of Italy in Sicily and Naples. These groups emerged from a need for local protection and control over land after long misuse of power by local officials. Since then, the Mafia, groups like the Cosa Nostra, the Camorra and the ‘Ndrangheta, have developed in a criminal organization of intimidation to commit crimes and acquire the management and control of economic activities, public contracts, and services in order to further their control on territory and ammas economic profit (Paoli, 2003). Through decades of existence and extensive infiltration of the vital fabrics of communities, including preying on young. Impressionable men from low-income household and poor communities, the Mafia exerts a form of social control that can be describes as similar to that of a private security system. The system ensures protection while imposing the respect of the criminal organization’s rules (Gambetta, 1993). Omertà requires the duty of loyalty, obedience and silence of affiliates, and the general cultural attitude around silence applies to everyone else, including women who are active victims of their male counterparts’ violent natures (Paoli, 2003). Given the mafia-type groups infiltration of Italian politics, business, and the legal/administrative systems (corruption, local government infiltration, vote-rigging) the public feels that law enforcement or the judiciary are not fully independent, or that the “system” works for insiders (Associated Press, 2024).

Laws Historically

Such distrust perpetuates underreporting and impunity allowing for the continued cycle of silence and a lack of accountability for abusers. When institutions fail to protect victims, femicide becomes not only an individual act of violence but also a reflection of systemic neglect. The Italian legislature has a long history of legislation that failed to protect women from violence, especially within family unites. Until recently violence against women has been historically overlooked by legislatures and even some extreme cases, condoned. In the 19030s during the fascist regime the Italian government developed and promulgated the penal code commonly referred to as “Codice Rocco” which emphasized that women were obligated to follow their husbands’ orders and reinforced gender roles that contributed to the idea that women were objects to be controlled by the husbands. It wasn’t until 1970 that divorce was legalized in Italy, and even after the fact it did not come close to resolving the issues of domestic violence and intimate partner femicide. “Honor Crime” statutes protected men who had claimed to kill their partners and female family members in the name of protecting his family’s honor. It was not until 1966, with the passing of Law 66 that sexual violence was official recognized as a crime punishable by time served, previously it had been a mere fine. Italy’s current penal code still fails to explicitly define or criminal femicide as a distinct offence. By subsuming these crimes under general homicide provisions and allowing broad judicial discretion in sentencing, the law continues to fall short of adequately recognizing and addressing the gendered nature of violence against women (Cinquemani 985).

The Italian Court System

The problem of femicide does just lie within the lacking legal protections afforded to women but is also in court proceedings and the narrative fostered during intimate partner violence cases. Victim’s testimony plays a pivotal role in domestic violence hearings, yet in Italian courts victim’s testimony is paradoxically elicited in the form of a confession, while the perpetrator is often absent or invoked their right to remain silent. The language used by the defense aims at trivializing domestic violence and the form of testimony that the court requires from the victims of intimate violence is violating and favors the perpetrators. The truthfulness of the victim’s testimony is questioned frequently, openly and without regard for any corroborating evidence, including physical injuring or a history of violence that the perpetrator has. As women take to the stand, their agency is once again questioned in a place that is supposed to uphold it. The Italian legal system essentially reproduces the conditions of violence against women, rendering their testimony incapable of achieving any legal significance. Women are perceived in such a way that they exist in mutually exclusive categories that are supposed to speak to their character, and their victimization. They are either too victim like, or too passive, or too confused, or conversely too precise, or too aware, or too strategic (Gribaldo, 2014). This is all just to say that Italian women are well aware of the fact that even if they pursue legal action against their abusers, the courts and judicial system actively work against them, limiting their ability to receive justice.

Gribaldo’s ethnographic research in domestic violence courts exposes how women’s testimonies are constrained by legal expectations of credibility and emotion. She writes of multiple cases in which she monitored and analyzed their experiences in court. Carlo, an expecting mother who was a couple months pregnant at the time of her attack illustrated how a survivor’s detached, monotone and unemotional testimony is interpreted as unreliable, or insincere; her “numb” demeanor, which was likely a trauma response, was judged as legal inadequacy, revealing how the justice system equates credibility with the performance of pain. Another unnamed woman who could not recall specific details of her abuse faced irritation from the judge who accuses her of exaggeration or indifference. This highlighted the system’s inability to accommodate trauma’s effects on memory, demanding coherent, chronological narratives over lived psychological truths. In a third example, a victim who fragmented account was reformulated by the judge in “let’s say it was every three months” shows how courts rewrite women’s testimonies to fit procedural logic which erases ambiguity and forced experiences of violence into quantifiable legal categories. Interviews with prosecutors and judges reveal that women must display an “appropriate emotional tone” with is neither too loud or too self-assured to be fully believed. Those who were too precise or assertive were at risk of being labeled manipulative while those who remained silent appeared to be uncooperative. The case of Giovanna, a Sicilian woman who testified against her Albanian ex-partner, exposed the intersections of class, race and gender in which her loud, expressive, dialect filled speech and “improper” courtroom behavior defied middle class decorum and the expected submissive victim archetype. Though ridicules by lawyers and judges, her theatrical self-presentation, subverts judicial norms and reveals how marginalized women’s voices are dismisses as excessive or irrational. It is such examples that characterize much of the Italian legal system and how it interacts with women of domestic violence. The legal system reproduces patriarchal hierarchies by demanding that women confess not only to their abuse but to their own moral character. Their credibility hinges on classed, racialized, and gendered ideals of modesty, emotion, and passivity, exposing a judiciary more invested in disciplining femineity than in delivering justices for victims of male violence.

Media Coverage

Italian media coverage of femicide often plays a powerful role in shaping public perception by determining which stories of violence are told and how. Rather than portraying femicide as the outcome of structural misogyny, many outlets sensationalize these crimes emphasizing the male perpetrator’s emotional state or motives and framing them as “crimes of passion”. Such portrayals obscure the systemic nature of gender-based violence and instead personalize the issue, reducing it to tragic but isolated domestic incidents. Victims, meanwhile, are frequently subjected to subtle or overt forms of victim-blaming: their clothing, relationship status, or personal behavior are scrutinized, while their suffering is detached from broader patterns of inequality. Women who testify to intimate violence often become “paradoxical victims” simultaneously held responsible for their own victimization and portrayed as passive recipients of male violence. This paradox mirrors the rhetoric of Italian media, where women are both pitied and blamed, their stories filtered through cultural expectations of morality, modesty, and femininity. This is where the Madonna-Whore complex also manifests. Such representations reinforce patriarchal stereotypes and delay the recognition of femicide as a structural, not individual, crime. However, feminist journalists and younger generations increasingly challenge these narratives, reframing coverage to center on systemic inequality, survivor agency, and the collective demand for justice (Gribaldo 2014).

Feminist Groups

In recent years, Italian women’s movements, survivors, and advocacy groups have mobilized to resist patriarchal systems and bring public attention to the femicide crisis. In terms of emerging institutional and societal responses, in May 2025, UN Women Italy and HeForShe Italy formally launched a national chapter which is a milestone for gender-equality mobilization in Italy. HeForShe Italy aims to bring together government institutions, civil society, academia, and the private sector to foster gender responsive policies, public awareness and community level programs against gender-based violence. The initiative explicitly targets systemic inequalities including but not limited to; Italy’s position at 87 on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report; Italian women’s workforce participation lags behind the EU average; and roughly one in three women in Italy reports having experienced some form of violence (HeForShe). Grassroots activism and support networks have also emerged actively combating gender-based violence, misogynistic rhetoric and aim to create institutions and resources for comprehensive care for victims of such violence and rhetoric. Organizations like D.i. Re or Donne in Rete Contra la Violenza and DonneXStrada provide essential services including legal support, mental health counseling, emergency shelters and safe space initiatives across Italy. Other groups like Semia Fund and La Malafimmina adopt an intersectional, long-term approach by supporting feminist organizing, economic empowerment for women, and channeling entrenched social norms, especially in marginalized underrepresented regions. These organizations emphasize prevention through education community outreach, safe-space creation, and support for survivors. They respond to femicide not only as an isolated criminal, violent crime but as part of systemic gender-based violence (Italia Segrata).

Comparative, Global Studies

Femicide is not a phenomenon isolated to just Italy, but is a global manifestation that crosses cultural, socio-economic, and geographic boundaries. UN Women cites that femicide is the most extreme form of violence against women and girls with tens of thousands of women and girls killed by intimate partners or family members. This is just to say that gender related killings of women and girls is a global emergency (UN Women). On average a woman or girl is killed by a partner or family member every 10 minutes (OSCE). Furthermore, there is no universally accepted definition of “femicide” across EU member states or globally which means comparisons between countries are forgotten, hampered by inconsistent definitions and data collection methods. This lack of definition means that the killing of women across the globe remains fairly “invisible” in statistics when they are classified under general homicide rather than as gender-motivated crimes (EIGE). The data fragmentation among European countries which include variation in legal definitions, reporting practices and data collection makes it difficult to draw precise cross-national comparisons or to assess trends reliably over time across all countries (UNODC). When positioning Italy within the broader European and global picture the Italian femicide case must be understood cautiously since the country is part of a larger structural problem, not an outlier phenomenon. Given underreporting and definitional disparities, Italy’s recorded femicides likely represent only a part of the gender related killings suggesting that comparisons with other countries or regions should account for data limitations, differences in classification, and protentional invisibility of many cases. Any comparative assessment as in Italy vs Europe, or Italy vs. the globe, must consider both per-capita rates and structural/contextual factors (especially since data collection, quality, legal definitions, social norms, and prevalence of intimate-partner violence). Understanding femicide as a global phenomenon underscores the need for internation cooperation, standardized definitions, and robust data collection. Not only for accurate comparison but also to inform effective prevention strategies.

Conclusion

In recent news, as response to mounting public outrage over the gender-based killings there has been legal recognition and legislative change. Italy’s parliament, in late November 2025, passed a law formal recognizing “femicide”. Under the law, femicide which is characterized as the killing of a woman motivated by her gender is a distinct crime punishable by life imprisonment (CNN). The new law reflects a shift. What had often been charged under general homicide statues will now be prosecuted under a gender-specific crime, aiming to highlight the structural dimension of violence against women (New York Times). The law’s passage coincides with broader governmental commitments: expanding funding for anti-violence centers and shelters, implementing awareness campaigns, and promoting educational initiatives to confront patriarchal norms from a young age (Al Jazeera). The creation of groups like HeForShe Italy and the active work of grassroots organizations illustrated a growing recognition that femicide is rooted not only in individual pathology, but in broader inequalities manifesting in Italy’s cultural, economic, and institutional systems. They all exist in tandem with one another perpetuating gender-based violence. Recent legislation marks a legal turning point, yet activists and scholarship emphasize that legal reform must be accompanied by sustained social and cultural change, educational program, social support systems economic empowerment and public awareness.

The persistence of femicide in Italy cannot be understood without acknowledging the deep interconnection between cultural, legal, and institutional structures that continue to uphold patriarchal power. From the enduring influence of the Catholic Church to the systemic failures of the justice system and the distortions perpetuated by media narratives, each layer of Italian society contributes to the normalization of gender-based violence. These intertwined forces have sustained a culture that simultaneously condemns and excuses violence against women, obscuring its structural roots beneath rhetoric of passion, honor, or morality. Yet, amid this long-standing inequality, there are signs of transformation. The growing visibility of feminist advocacy, grassroots activism, and youth movements reflects a cultural shift toward accountability and justice. Future research should focus on the cultural and educational reforms needed to dismantle entrenched gender norms and strengthen institutional protections for women. Only by confronting these intersecting systems and fostering an environment grounded in equality and awareness can Italy move closer to eradicating femicide and ensuring true justice for all women.

Works Cited

Accati, Luisa. “Explicit Meanings: Catholicism, Matriarchy and the Distinctive Problems of Italian Feminism.” Gender & History 7, no. 2 (1995): 241–259.

Crivellone, S. D. “‘The Italian Job’: How Italy’s Long History of Catholicism Has Shaped Gender Roles and Sexual Politics.” Senior Thesis, Fordham University, 2020. https://research.library.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=international_senior

Kelly, Joan. “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” in Becoming Visible: Women in European History, edited by Renate Bridenthal and Claudia Koontz, 19–50. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977. https://nguyenshs.weebly.com/uploads/9/3/7/3/93734528/kelly_did_women_have_a_renaissanace.pdf

Martin Bull & Laura Polverari. (2025) The Meloni government: consolidation and a return to politics. Contemporary Italian Politics 17:2, pages 130-144

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Measuring Femicide in Italy. 2021. https://eige.europa.eu/publications/measuring-femicide-italy

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Gender-Based Violence: Country

Profile – Italy. 2024. https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/countries/italy

Ministero dell’Interno. 8 Marzo – Donne Vittime di Violenza. Rome, 2021. https://www.interno.gov.it/sites/default/files/2021-03/report_2021_-_donne_vittime_di_violenza.pdf

Ministero dell’Interno. Report settimanale al 26 novembre 2023. https://www.interno.gov.it/it/notizie/femminicidi-dati-e-analisi-2023

IMPRODOVA. Data and Statistics in Italy. 2023. https://training.improdova.eu/en/data-and-statistics/data-and-statistics-in-italy/

ISTAT (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica). Analisi delle Sentenze di Femminicidio.

Rome, 2018. https://www.istat.it/it/files//2018/04/Analisi-delle-sentenze-di-Femminicidio-Ministero-di-Giustizia.pdf

EURES Ricerche Economiche e Sociali. Rapporto sull’Omicidio in Famiglia. 2020. https://www.eures.it/sintesi-rapporto-eures-omicidio-in-famiglia/

UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Study on Homicide – Gender-Related Killing of Women and Girls. Vienna, 2019. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/global-study-on-homicide.html

Eurostat. Intentional Homicides Database (crim_hom_vrel). 2018 Edition. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/crim_hom_vrel/default/table

European Data Journalism Network (EDJNet). Femicide Remains All Too Common in Italy and Europe. 2023. https://www.europeandatajournalism.eu/cp_data_news/femicide-remains-all-too-common-in- italy-and-europe/

National Catholic Register. “Rome’s ‘Madonnelle’: What Are the Marian Shrines on Street Corners?” National Catholic Register, August 24, 2024. https://www.ncregister.com/blog/street-corner-marian-shrines-in-rome.

Giordano, C., Cannizzaro, G., Tosto, C., Pavia, L., & Di Blasi, M. (2017). Promoting Awareness about Psychological Consequences of Living in a Community Oppressed by the Mafia: A Group-Analytic Intervention. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01631

“Italy’s G7 Chair Turns Focus on Fighting Mafia, Organized Crime.” Associated Press, 12 Sept. 2024, https://apnews.com/article/italy-g7-mafia-organized-crime-27d54a5dd551c2dfbbea5489ad9cca00

The Guardian. (2024, November 26). ‘We need a cultural revolution’: Femicide victim’s family seek change in Italy. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/nov/26/we-need-a-cultural-revolution-femicide-victims-family-seek-change-in-italy

GC Human Rights. (2023). Giulia Cecchettin’s murder: The femicide that awoke Italy to its patriarchal reality. https://www.gchumanrights.org/preparedness/giulia-cecchettins-murder-the-femicide-that-awoke-italy-to-its-patriarchal-reality/

Euronews. (2023, June 9). A brutal murder has prompted Italy to boost its laws against gender-based violence. https://www.euronews.com/2023/06/09/a-brutal-murder-has-prompted-italy-to-boost-its-laws-against-gender-based-violence-is-it-e

Newsweek. (2020, December 16). Italian man acquitted of murdering wife due to ‘delirium of jealousy’. https://www.newsweek.com/antonio-gozzini-acquitted-murder-wife-mental-incapacity-jealousy-delirium-1553890

Yahoo News. (2020). Italy grapples with patriarchal history amid femicide outrage. https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/brutal-epidemic-domestic-violence-sparks-123252347.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAEVqQ302tROBr1Kn8jlXPsgH22PzYvOeU95VQXXRualAj1DCPVq6rMkh4OMlzXRb_KNCVUdxfnxkwRjipw63lXvPnXdx0OoFCjpcv1Jm_dZUWzA5pffql1YCzJIHqAIr6C_jbAF6VM0Y43ir1UF1g2VI1NrX9cA9Bezl4_sKfmzx

Gambetta D. (1993). The Sicilian Mafia: the Business of Private Protection. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Sicilian_Mafia/y3bv3tqWftYC?hl=en&gbpv=1

Paoli L. (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. https://gudangdownloadebook.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/mafia-brotherhoods-organized-crime-italian-style.pdf

Cinquemani, Deanna. “That’s Amore?: Intimate Partner Femicide in Italy and the Failures of the Italian Legislature to Prevent Violence Against Women.” Family Court Review, vol. 62, no. 4, 2024, pp. 985-999. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12825

Gribaldo, A. (2014), The paradoxical victim: Intimate violence narratives on trial in Italy. American Ethnologist, 41: 743-756. https://doi-org.proxy.binghamton.edu/10.1111/amet.12109

HeForShe. UN Women Italy Launches National HeForShe Chapter in Italy. Accessed January 2025 https://www.heforshe.org/en/un-women-italy-launches-national-heforshe-chapter-italy

Italia Segreta. “Organizations Against Gender Violence in Italy.” Italy Segreta. Accessed January 2025. https://italysegreta.com/organizations-against-gender-violence/.

Horowitz, Jason. “Italy Adds ‘Femicide’ to Criminal Code amid Outcry over Violence Against Women.” The New York Times, November 26, 2025.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/26/world/europe/italy-femicide-violence-women.html

Italy Introduces Femicide Law – Country Adds New Criminal Offence.” CNN, November 25, 2025. https://www.cnn.com/2025/11/25/europe/italy-femicide-law-intl-hnk

Al Jazeera, “Italy Adds Femicide to Its Criminal Code to Curb Violence Against Women,” November 26, 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/11/26/italy-adds-femicide-to-the-criminal-code-to-curb-violence-against-women

UN Women. “Five Essential Facts to Know About Femicide.” UN Women, 2025.

https://www.unwomen.org/en/articles/explainer/five-essential-facts-to-know-about-femicide

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE).

Measuring Femicide in the European Union and Internationally: An Assessment.

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021.

https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/20211564_mh0421097enn_pdf_0.pdf

Pereira, Marina E., et al. “Gender-Based Violence and Femicide: A Global Health Issue.”

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12 (2022).

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9223675/

Sage Publications. “Femicide in Europe: Understanding the Structural Patterns of Gender-Related Killings.” Media, Culture & Society (2025). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/01634437251336149

Womankind Worldwide. Femicide Factsheet: Global Statistics and Calls to Action.

Womankind resources archive, 2023.

https://www.womankind.org.uk/resource/a-femicide-factsheet-global-stats-calls-to-action/

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 2004. https://suny-bin.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma990017115650204802&context=L&vid=01SUNY_BIN:01SUNY_BIN&lang=en&search_scope=BINGSUNY&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=Everything&query=any,contains,caliban%20and%20the%20witch&offset=0

Bourdieu, Pierre. Masculine Domination. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. https://monoskop.org/images/a/a4/Bourdieu_Pierre_Masculine_Domination_2001.pdf

Segato, Rita Laura. La guerra contra las mujeres. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños, 2016. https://journals.openedition.org/amerika/10981

Hall, Stuart. “The Work of Representation.” In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, 13–74. London: Sage, 1997. https://eclass.aueb.gr/modules/document/file.php/OIK260/S.Hall%2C%20The%20work%20of%20Representation.pdf

Russell, Diana E. H., and Jill Radford, eds. Femicide: The Politics of Woman Killing. New York: Twayne, 1992. https://heinonline-org.proxy.binghamton.edu/HOL/Page?lname=&public=false&collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/anzjc27&men_hide=false&men_tab=toc&kind=&page=210

Walby, Sylvia. Theorizing Patriarchy. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/21680/1/1990_Walby_Theorising_Patriarchy_book_Blackwell.pdf